The Blue Bird (fairy tale)

| The Blue Bird | |

|---|---|

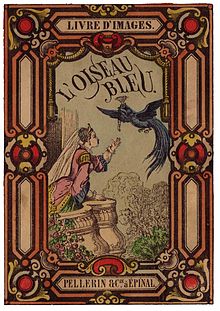

The princess is given a necklace by the Prince, under the guise of a blue bird. | |

| Folk tale | |

| Name | The Blue Bird |

| Also known as | L'oiseau bleu |

| Aarne–Thompson grouping | ATU 432 (The Prince as Bird; The Bird Lover) |

| Region | France |

| Published in | Les Contes des Fées (1697), by Madame d'Aulnoy |

| Related | The Feather of Finist the Falcon; The Green Knight |

"The Blue Bird" (French: L’oiseau bleu) is a French literary fairy tale by Madame d'Aulnoy, published in 1697.[1] An English translation was included in The Green Fairy Book, 1892, collected by Andrew Lang.[2][3][4]

The tale is Aarne–Thompson type 432, The Prince as Bird. Others of this type include "The Feather of Finist the Falcon", "The Green Knight", and "The Greenish Bird".

Plot summary

[edit]

After a wealthy king loses his dear wife, he meets and falls in love with a woman, who is also recently widowed and they marry. The king has a daughter named Florine and the new queen also has a daughter named Truitonne. While Florine is beautiful and kind-hearted, Truitonne is spoiled, selfish and ugly and it is not too long before she and her mother become jealous of Florine's beauty.

One day, the king decides the time has come to arrange his daughters' marriages and soon, Prince Charming visits the kingdom. The queen is determined for him to marry Truitonne, so she dresses her daughter in all her finery for the reception and bribes Florine's ladies-in-waiting to steal all her dresses and jewels. But her plan backfires for when the Prince claps eyes on Florine, he falls in love with her at once and pays attention only to her. The queen and Truitonne are so furious that they badger the king until he agrees to lock Florine up for the length of the visit and they attempt to blacken her character to the Prince.

The queen sends Prince Charming many gifts, but when he hears they are from Truitonne, he rejects them. The queen angrily tells him that Florine will be locked in a tower until he leaves. Prince Charming is outraged and begs to speak with Florine for a moment. The devious queen agrees, but she goes to meet the Prince instead. In the darkness of their meeting place, Prince Charming mistakes Truitonne for Florine and unwittingly asks for the princess's hand in marriage.

Truitonne conspires with her fairy godmother, Mazilla, but Mazilla tells her it will be difficult to deceive the Prince. At the wedding ceremony, Truitonne produces the Prince's ring and pleads her case. When Prince Charming realises he has been tricked, he refuses to marry her and nothing that Truitonne or Mazilla do can persuade him. At last, Mazilla threatens to curse him for breaking his promise and when Prince Charming will still not agree, Mazilla transforms him into a blue bird.

The queen, on hearing of the news, blames Florine; she dresses Truitonne as a bride and shows her to Florine, claiming that Prince Charming has agreed to marry her. She then persuades the King that Florine is so infatuated with Prince Charming that she had best remain in the tower until she comes to her senses. However, the bluebird flies to the tower one evening and tells Florine the truth. Over many years, the bluebird visits her often, bringing her rich gifts of jewels.

Over the years, the queen continues to look for a suitor for Truitonne. One day, exasperated by the many suitors that have rejected Truitonne, the Queen seeks Florine in her tower, only to find her singing with the bluebird. Florine opens the window to let the bird escape, but the Queen discovers her jewellery and realises that she has been receiving some kind of aid. She accuses Florine of treason, but the bluebird manages to foil the queen's plot.

For many days, Florine does not call the bluebird for fear of the queen's spy; but one night, as the spy sleeps soundly, she calls the bluebird. They continue to meet for some nights thereafter until the spy hears one of their meetings and tells the Queen. The Queen orders for the fir tree, where the bird perches, to be covered with sharp edges of glass and metal, so that he will be fatally wounded and unable to fly. When Florine calls for the bluebird and he perches on the tree, he cuts his wings and feet and cannot fly to Florine. When the bluebird does not answer Florine's call, she believes he has betrayed her. Luckily, an enchanter hears the Prince lamenting and rescues him from the tree.

The enchanter persuades Mazilla to change Prince Charming back into a man for a few months, after which if he still refuses Truitonne, he will be turned back into a bird.

One day, Florine's father dies and the people of the kingdom rise up and demand Florine's release. When the Queen resists, they kill her and Truitonne flees to Mazilla. Florine becomes queen and makes preparations to find King Charming.

Disguised as a peasant woman, Florine sets out on a journey to find the King and meets an old woman, who proves to be another fairy. The fairy tells her that King Charming has returned to his human form after agreeing to marry Truitonne and gives her four magical eggs. The first egg she uses to climb a great hill of ivory. The second contains a chariot pulled by doves that brings her to King Charming's castle, but she can not reach the king in her disguise. She offers to sell to Truitonne the finest jewellery that King Charming had given her, and Truitonne shows it to the King to find out the proper price. He recognizes it as the jewellery he gave to Florine and is saddened. Truitonne returns to Florine, who will sell them only for a night in the Chamber of Echoes, which King Charming had told her of one night: whatever she says in there will be heard in the king's room. She reproaches him for leaving her and laments all night long, but he has taken a sleeping potion, and does not hear her.

She breaks the third egg and finds a tiny coach drawn by mice. Again, she trades it for the Chamber of Echoes, and laments all the night long again, but only the pages hear her.

The next day, she opens the last egg and it holds a pie with six singing birds. She gives it to a page, who tells her that the King takes sleeping potions at night. She bribes the page with the singing birds and tells him not to give the King a sleeping potion that night. The King, being awake, hears Florine and runs to the Chamber of Echoes. Recognising his beloved, he throws himself at her feet and they are joyfully reunited.

The enchanter and the fairy assure them that they can prevent Mazilla from harming them, and when Truitonne attempts to interfere, they quickly turn her into a sow. King Charming and Queen Florine are married and live happily ever after.

Publication history

[edit]The tale of "The Blue Bird" (L'Oiseau Bleu) is one of Madame d'Aulnoy's most famous fairy tales,[5] with republications in several compilations.[6]

The tale was renamed Five Wonderful Eggs and published in the compilation Fairy stories my children love best of all.[7]

Legacy

[edit]The tale was one of many from d'Aulnoy's pen to be adapted to the stage by James Planché, as part of his Fairy Extravaganza.[8][9][10] The tale was retitled as King Charming, or the Blue Bird of Paradise when adapted to the stage.[11][12]

Analysis

[edit]Tale type

[edit]The tale is classified, in the international Aarne-Thompson-Uther Index, as tale type ATU 432, "The Prince as Bird". In the French Catalogue, d'Aulnoy's tale gives its name to the French tale type AT 432, L'Oiseau Bleu.[13]

Motifs

[edit]French folklorists Paul Delarue and Marie-Louise Ténèze noted that in d'Aulnoy's tale, the heroine bribes her step-sister with precious objects to allow for access to Charmant. This motif does not appear in other oral variants of the same type, but it does occur as an episode of type ATU 425A, "The Animal (Monster) as Bridegroom".[14] Also, according to both Delarue and Ténèze, the motif of heroine's lover in bird shape is "characteristic" of international variants.[15]

Variants

[edit]Europe

[edit]In a Greek tale, The Merchant's Daughter, Daphne, the youngest of the titular merchant's daughters, asks for her father to bring her "The Golden Ring". The Golden Ring is a prince from a foreign country (India) who, after meeting the merchant, tells him he saw Daphne in his dreams and wishes to marry her. The merchant gives his daughter a letter, a cup and the golden ring. The prince metamorphoses into a pigeon to meet Daphne by her window in secret, flies in and jumps into a cup to become human. Some time later, jealous of her hidden happiness, her sisters see that a knife is inside the cup and summon the prince to be hurt while in bird form. It happens thus, and Prince Fortunate (the prince's name) flies back to his kingdom. Learning of her beloved's injuries, Daphne dons a masculine disguise, sails to India and wanders to her prince's kingdom. On the way, she overhears the conversation between two birds about a way to cure the prince: one would have to kill the birds and dip their bodies in a spring to make an ointment that can heal the prince. Daphne kills the birds, prepares the ointment and goes to Prince Fortunate's castle in a doctor's disguise to apply the cure on his body.[16]

In an Armenian tale published both by author A. G. Seklemian and Armenian literary critic Hakob S. Khachatryan with the title "Невеста родника" ("The Bride of the Fountain"), a mother goes to the market to buy dresses for her three daughters, but forgets about the gift for her youngest. She stops by a fountain and sighs: "Eh!" ("Tush", in Seklemian's translation). Suddenly, a man jumps out of the fountain and asks the woman about the matter. After hearing about the dress, the man suggests she takes her daughter to the fountain and shout "Eh!". The woman bring her daughter to the fountain, shouts "Eh!", the man appears and gives her the dress. The woman leaves her daughter with the man in the fountain and two months later, the girl returns. The man comes to the girl's window at night in the form of a partridge. The girl's sisters begin to envy her happiness and place razors on the window, for the next time the man flies in. And so it happens: the man flies in, injures himself in the razors and flies back to where he came from. Days pass, and the girl, sensing something is wrong with her husband, decides to look for him. The girl goes back to the fountain, summons her husband and father-in-law with "Eh!". The bridegroom asks his father to wear his eagle outfit, fly away with the girl and drop her in the desert. He carries out his son's orders and the girl ends up lost in the desert. Composing herself, she wanders off through the dunes until she reaches two dervishes talking about curing diseases: to heal razor wounds, one needs only milk from a nursing mother who just gave birth to a son, and dried blood. The girl goes to the fountain again with the remedy and treats her bridegroom's wounds.[17][18] French author Frédéric Macler translated the tale into French as La fiancée de la source.[19]

In a Georgian tale titled "Крахламадж" ("Krahlamaj"), a king has three daughters who are supervised by a governess. One day, he has to go on a journey and asks his daughters what they want as presents from the trip: the eldest asks for a dress unlike any other, the middle one for a jewel that shines brighter than the sun, and the youngest for the krahlamaj flower. The king goes on his journey and finds gifts for the elder ones, but cannot seem to find the krahlamaj, since no one appears to have heard of it. The king then reaches a distant kingdom, where a prophetess knows about the krahlamaj flower, and explains the situation: the king of this distant kingdom prayed to God for a son, even if he is an angel from Heaven, and God granted him one; at the same time, a flower sprouted at the garden and, a few days later, the little baby grew wings and flew back to Heaven; the king becomes sad, but another angel explains that his son can be summoned back to Earth by placing shiny objects and petals from the krahlamaj flower in a room, and clean it from any piece of glass. The prophetess then tells the first king that the flower is fiercely guarded by animals in the king's garden, but he can avoid them by throwing them fresh meat. The first king takes the flower and goes back to his daughters, giving them the presents. The princesses' governess, who worked at the second king's palace, knows the secret of the krahlamaj flower, so she puts it in a pot, places some shiny objects and some petals in a room, and prince Krahlamaj flies down from Heaven to meet the youngest princess. Later, the eldest princess spies on the cadette and, seeing the beautiful, angelic youth, grows jealous, and hatches a plan: the elder princess places glass on the bed and, when Krahlamaj appears next, he hurts himself and flies back to his kingdom badly hurt. Sensing her beloved's disappearance, the youngest princess dresses in masculine attire, takes the krahlamaj flower she owned and rushes to the prince's distant kingdom. She reaches her beloved's kingdom, where she learns the prince has been bedridden for years, so she introduces herself as a magician who has come to cure the prince, and is takes to his chambers. The princess enters the chambers and sees the injured prince, and, just as she comes, the smell of the krahlamaj flower she brought with her begins to heal the prince. After he is completely cured, the princess and the prince marry.[20]

Asia

[edit]Middle East

[edit]In a Middle Eastern tale titled Tamara, the titular Tamara is a beautiful girl, the youngest of three poor sisters. One day, she finds a magical talking peacock, who tells her he is Prince Bahadin, cursed by a sorcerer on his half-brothers' orders to become a peacock by dawn and human at night. They spend nights together, and he leaves a bag of gold coins for her, then departs in bird form. Eventually, Bahadin and Tamara marry, and he allows his sisters-in-law to live with them. One day, the couple converse about something that may endanger his life: shards of broken glass. Somehow, one of Tamara's sisters, Layal, places some on the windowpane. Bahadin flies in the room in peacock form and is badly hurt by it, then makes a return for his kingdom in Mount Carmel. Tamara learns of her beloved's ordeal and rides to find a cure for him.[21]

Iraq

[edit]Russian professor V. A. Yaremenko published an Iraqi tale that combined tale types ATU 432 and 425D, "Vanished Husband [Learned of By Keeping Inn/Bath-house]"), and claimed that it was "very popular" among populations who dwell in Shatt al-Arab.[22]

Africa

[edit]Egypt

[edit]Scholar Hasan El-Shamy collected an Egyptian tale in 1971 from a female storyteller. In this tale, titled Pearls-on-Vines, a king has to go the peregrination to Mecca and asks his three daughters what presents they want when he comes back. The two elders insist on material possessions, while the youngest only wishes for his safe return. The two sisters insist that their younger sibling must be wishing for something. An old woman advises her to asks for "Pearls-on-Vines", who is actually "the son of the king of the Moslem jinn". The prince Pearls-on-Vines appears to him in a dream and tells him to pass along instructions to his daughter: to make a hole in the wall and sprinkle it with rosewater. The prince materializes in the princess's room in the form of a snake, and her sisters prepare a trap for him.[23]

Algeria

[edit]In an Arab Algerian tale collected by engineer Jeanne Scelles-Millie with the title La Fille du Roy et le Rosier ("The King's Daughter and the Rosebush"), a king has seven daughters, the youngest of which he loves the best of all, to her sisters' jealousy. One day, their father is ready to go to Mecca, and asks what presents he can bring him. They each ask for material gifts, but the youngest seems uncertain about her gift. Her elder sisters consult with a sorceress, who advises them to suggest a rosebush for their sister. The youngest princess follows her sisters' suggestion and asks the king for a rosebush, and curses her father not to come back until he finds her gift. The king goes to Mecca and buys gifts for his six elder daughters, but cannot seem to find the specific rosebush, and his camel does not move at all. The king is advised by an old man to stop by a cave entrance, sacrifice a ram and wait until a white dog comes to take the meat. It happens thus: the king sees a black dog and a white dog come out of the cave and take the meat. He enters the cave and meets a prince, who asks him the purpose of his visit. The king explains about his search for a gift for his daughter, and the prince says he is the rosebush, and orders the man to return home, for he will come to his daughter through the air and with the storm and the rain. The king returns home and tells his youngest daughter about the prince. The youngest princess waits in her room for the rosebush prince, talks to him all night and he flies away, leaving her some gold in the morning. As time passes, her elder sisters begin to envy her good fortune, and place needles by the window. The next time the rosebush prince flies in, he injures himself in the needles and has to fly back to his kingdom. The youngest princess decides to seek him out, and stops by a lion's den. She overhears a conversation between a lion and a lioness about the rosebush prince and how their liver and heart can cure him. After the lions sleep, the princess kills them to take their heart and liver to cure the prince.[24]

In a tale collected in Algers and translated to French as Djebel Lakhdar, la Montaigne Verte ("Djebel Lakhdar, Green Mountain"), on her weaving teacher's request, a young woman named Zineb kills her mother to allow for her teacher to marry her father. However, after the woman marries the girl's father, she begins to mistreat her former student, now her stepdaughter. Zineb regrets having agreed to do her teacher's request to marry her father, now that she suffers her fury. Some time later, Zineb's father decides to go on a pilgrimage, and asks Zineb and his seven stepdaughters what gifts he can bring them: they ask for precious objects, while Zineb asks her father to greet sompne named Djebel Lakhdar for her. After he leaves, Zineb's stepmother expels her from the house. Zineb's father returns home with Djebel Lakhdar's return gift: seven nuts for Zineb. The girl breaks open each one and produces a large palace, servants, carpets, and two vases, one of silver and the other of gold. In the same night, Djebel Lakhdar flies in through Zineb's window in the shape of a green bird, dives into the vases of silver and gold, which are filled with water, and turn into a person. In time, Zineb's stepmother learns of the clandestine affairs, and places some ground powder in the vases for the next time Djebel Lakhdar returns. It happens thus: the man dives in bird form, is severely injured, and makes a turn back home. Zineb discovers her lover is missing and goes after him: wearing male garments, she reaches his kingdom, where she learns prince Djebel Lakhdar is injured. Zineb, in the disguise of a male doctor, tends to the prince's body and heals him. She returns home to the palace produced by the magic nut, and waits for her lover. Djebel Lakhdar rides a horse back to Zineb, intent on killing her for a supposed betrayal, but Zineb reveals she was the doctor who cured him. They reconcile.[25][26]

America

[edit]Author Elsie Spicer Eells recorded a Brazilian variant titled The Parrot of Limo Verde (Portuguese: "O Papagaio do Limo Verde"): a beautiful princess receives the visit of a parrot (in fact, a prince in disguise).[27]

Mentions in other works

[edit]In the autobiography The Words from Jean-Paul Sartre, The Blue Bird was mentioned by the author as one of the first books he liked as a child.

In the ballet, The Sleeping Beauty, the Bluebird and Princess Florine make an appearance at Aurora's wedding celebration.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Miss Annie Macdonell and Miss Lee, translators. "The Blue Bird Archived 2020-02-21 at the Wayback Machine" The Fairy Tales of Madame D'Aulnoy. London: Lawrence and Bullen, 1892.

- ^ Andrew Lang, The Green Fairy Book, "The Blue Bird"

- ^ Buczkowski, Paul (2009). "The First Precise English Translation of Madame d'Aulnoy's Fairy Tales". Marvels & Tales. 23 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1353/mat.2009.a266895. JSTOR 41388901.

- ^ Palmer, Nancy; Palmer, Melvin (1974). "English Editions of French 'Contes de Fees' Attributed to Mme D'Aulnoy". Studies in Bibliography. 27: 227–232. JSTOR 40371596.

- ^ Planché, James Robinson. Fairy Tales by The Countess d'Aulnoy, translated by J. R. Planché. London: G. Routledge & Co. 1856. p. 610.

- ^ Thirard, Marie-Agnès (1993). "Les contes de Madame d'Aulnoy : lectures d'aujourd'hui". Spirale. Revue de recherches en éducation. 9 (1): 87–100. doi:10.3406/spira.1993.1768.

- ^ Shimer, Edgar Dubs. Fairy stories my children love best of all. New York: L. A. Noble. 1920. pp. 213-228.

- ^ Feipel, Louis N. (September 1918). "Dramatizations of Popular Tales". The English Journal. 7 (7): 439–446. doi:10.2307/801356. JSTOR 801356.

- ^ Buczkowski, Paul (2001). "J. R. Planché, Frederick Robson, and the Fairy Extravaganza". Marvels & Tales. 15 (1): 42–65. doi:10.1353/mat.2001.0002. JSTOR 41388579. S2CID 162378516.

- ^ MacMillan, Dougald (1931). "Planché's Fairy Extravaganzas". Studies in Philology. 28 (4): 790–798. JSTOR 4172137.

- ^ Adams, W. H. Davenport. The Book of Burlesque. Frankfurt am Main, Germany: Outlook Verlag GmbH. 2019. p. 74. ISBN 978-3-73408-011-1

- ^ Planché, James (1879). Croker, Thomas F.D.; Tucker, Stephen I. (eds.). The extravaganzas of J. R. Planché, esq., (Somerset herald) 1825-1871. Vol. 4. London: S. French. pp. Vol 4, pp. 89–90.

- ^ Delarue, Paul. Le conte populaire français: catalogue raisonné des versions de France et des pays de langue française d'outre-mer: Canada, Louisiane, îlots français des États-Unis, Antilles françaises, Haïti, Ile Maurice, La Réunion. Érasme, 1957. pp. 112-113.

- ^ Delarue, Paul. Le conte populaire français: catalogue raisonné des versions de France et des pays de langue française d'outre-mer: Canada, Louisiane, îlots français des États-Unis, Antilles françaises, Haïti, Ile Maurice, La Réunion. Maisonneuve & Larose, 1997. p. 114.

- ^ Delarue, Paul. Le conte populaire français: catalogue raisonné des versions de France et des pays de langue française d'outre-mer: Canada, Louisiane, îlots français des États-Unis, Antilles françaises, Haïti, Ile Maurice, La Réunion. Maisonneuve & Larose, 1997. p. 114.

- ^ Baring, Maurice. The Blue Rose Fairy Book. New York: Maude, Dodd and Company. 1911. pp. 193-218.

- ^ Seklemian, A. G. (1898). The Golden Maiden and Other Folk Tales and Fairy Stories Told in Armenia. New York: The Helmen Taylor Company. pp. 49–53.

- ^ Хачатрянц, Яков Самсонович. "Армянские сказки". Moskva, Leningrad: ACADEMIA, 1933. pp. 60-63.

- ^ Macler, Frédéric. Contes arméniens. Paris: Ernest Leroux Editeurs. 1905. pp. 65–70.

- ^ Грузинские народные сказки [Georgian Folk Tales]. Сост., вступит, статья, примеч. и типолог. анализ сюжетов Т. Д. Курдованидзе. Book 1. Moskva: Главная редакция восточной литературы издательства «Наука», 1988. pp. 199-204 (tale nr. 50), 356 (classification).

- ^ Ben Odeh, Hikmat. Classic Fairy Tales from Ancient Palestine and Jordan. H. Ben Odeh, 1995. pp. 58-78.

- ^ Сказки и предания Ирака. Сост., пер. с араб., вступит, ст. и примеч. В. А. Яременко. М.: Наука. Главная редакция восточной литературы, 1990. p. 32 (note on Tale nr. 3).

- ^ El-Shamy, Hasan. Tales Arab Women Tell and the Behavioral Patterns They Portray. Indiana University Press, 1999. pp. 262-269, 442. ISBN 9780253335296.

- ^ Scelles-Millie, Jeanne. Contes sahariens du Souf. G.-P. Maisonneuve et Larouse, 1963. pp. 291-297.

- ^ Dermenghem, E. "Le mythe de Psyché dans le folklore nord-africain". In: Revue africaine 1º—2e trim., 1945, p. 48.

- ^ Sari Mohammed, Leila (2017). Contes Et Récits Du Maghreb Territoires De L’imaginaire Et Enjeux Socioculturels (PDF) (Doctor's Thesis) (in French). Tlemcen: Université Abou Bekr Belkaid. pp. 217–218.

- ^ Eells, Elsie Spicer. The Brazilian Fairy Book. New York: Frederick A. Stokes company, 1926. pp. 132-139.

External links

[edit] Media related to The Blue Bird (fairy tale) at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to The Blue Bird (fairy tale) at Wikimedia Commons The full text of The Blue Bird at Wikisource

The full text of The Blue Bird at Wikisource