Timeline of religion

This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2016) |

Religion has been a factor of the human experience throughout history, from pre-historic to modern times. The bulk of the human religious experience pre-dates written history, which is roughly 70,000 years old.[1] A lack of written records results in most of the knowledge of pre-historic religion being derived from archaeological records and other indirect sources, and from suppositions. Much pre-historic religion is subject to continued debate.

Religious practices in prehistory

[edit]Middle Paleolithic (200,000 BCE – 50,000 BCE)

[edit]Despite claims by some researchers of bear worship, belief in an afterlife, and other rituals, current archaeological evidence does not support the presence of religious practices by modern humans or Neanderthals during this period.[2]

- 100,000 BCE: Earliest known human burial in the Middle East.

- 78,000 BCE – 74,000 BCE: Earliest known Homo sapiens burial of a child in Panga ya Saidi, East Africa.

- 70,000 BCE – 35,000 BCE: Neanderthal burials take place in areas of Europe and the Middle East.[3]

50th to 11th millennium BCE

[edit]- 40,000 BCE: The remains of one of the earliest known anatomically modern humans to be discovered cremated, was buried near Lake Mungo.[4][5][6][7][8]

- 38,000 BCE: The Aurignacian[9] Löwenmensch figurine, the oldest known zoomorphic (animal-shaped) sculpture in the world and one of the oldest known sculptures in general, was made. The sculpture has also been interpreted as anthropomorphic, giving human characteristics to an animal, although it may have represented a deity.[10]

- 35,000 BCE – 26,001 BCE: Neanderthal burials are absent from the archaeological record. This roughly coincides with the appearance of Homo sapiens in Europe and decline of the Neanderthals;[3] individual skulls and/or long bones began appearing, heavily stained with red ochre and separately buried. This practice may be the origin of sacred relics.[3] The oldest discovered "Venus figurines" appeared in graves. Some were deliberately broken or repeatedly stabbed, possibly representing the murders of the men with whom they were buried,[3] or owing to some other unknown social dynamic.[citation needed]

- 25,000 BCE – 21,000 BCE: Clear examples of burials are present in Iberia, Wales, and eastern Europe. These, too, incorporate the heavy use of red ochre. Additionally, various objects were included in the graves (e.g. periwinkle shells, weighted clothing, dolls, possible drumsticks, mammoth ivory beads, fox teeth pendants, panoply of ivory artifacts, "baton" antlers, flint blades etc.).[3]

- 13,000 BCE – 8,000 BCE: Noticeable burial activity resumed. Prior mortuary activity had either taken a less obvious form or contemporaries retained some of their burial knowledge in the absence of such activity. Dozens of men, women, and children were being buried in the same caves which were used for burials 10,000 years beforehand. All these graves are delineated by the cave walls and large limestone blocks. The burials share a number of characteristics (such as use of ochre, and shell and mammoth ivory jewellery) that go back thousands of years. Some burials were double, comprising an adult male with a juvenile male buried by his side. They were now beginning to take on the form of modern cemeteries. Old burials were commonly re-dug and moved to make way for new ones, with the older bones often being gathered and cached together. Large stones may have acted as grave markers. Pairs of ochred antlers were sometimes mounted on poles within the cave; this is compared to the modern practice of leaving flowers at a grave.[3]

10th to 6th millennium BCE

[edit]- 10,000 BCE – 8,000 BCE: The Baghor stone from presumably one of the oldest Shakti shrines in India, and one of the oldest sites of worship yet discovered in the world, is estimated to have been formed during this period (9000-8000 BCE). However, it may predate 10,000 BCE as samples were dated to 11,870 (± 120) YBP in a 1983 publication.[11] The living shrine at which it was found is currently used as a place for worshipping Devi by both Hindus and Indian Muslims. The triangular shape of the stone is that of the Kali Yantra which is also still in use across India. The Kol and Baiga tribes consider the triangular shape to symbolise the mother goddess 'Mai', variously named Kerai, Kari, Kali, Kalika or Karika.[12]

- 9130 BCE – 7370 BCE: This was the apparent period of use of Göbekli Tepe, one of the oldest human-made sites of worship yet discovered; evidence of similar usage has also been found in another nearby site, Nevalı Çori.[13]

- 7500 BCE – 5700 BCE: The settlements of Çatalhöyük developed as a likely spiritual center of Anatolia. Possibly practising worship in communal shrines, its inhabitants left behind numerous clay figurines and impressions of phallic, feminine, and hunting scenes.[citation needed]

- 7250 BCE – 6500 BCE: The Ayn Ghazal statues were made in Jordan during the Neolithic.[14] These statues were argued to have been gods, legendary leaders, or other figures of power. They were suggested to have been a representation of a fusion of previously separate communities by Gary O. Rollefson.[15]

Before Common Era(BCE)

[edit]

- Late 4th millennium BCE: Sumerian Cuneiform emerged from the proto-literate Uruk period, allowing the codification of beliefs and creation of detailed historical religious records.[16]

- 3200 BCE – 3100 BCE: Newgrange, the 250,000 short tons (230,000 t) passage tomb aligned to the winter solstice in Ireland, was built.[17]

- 3100 BCE: The initial form of Stonehenge was completed. The circular bank and ditch enclosure, about 110 metres (360 ft) across, may have been completed with a timber circle.

- 2900 BCE: The second phase of Stonehenge was completed and appeared to function as the first enclosed cremation cemetery in the British Isles.

- 2635 BCE – 2610 BCE: The oldest surviving Egyptian pyramid was commissioned by Pharaoh Djoser.[18]

- 2600 BCE: Stonehenge began to take on its final form. The wooden posts were replaced with bluestone. It began taking on an increasingly complex setup (including an altar, a portal, station stones, etc.) and shows consideration of solar alignments.

- 2560 BCE: This is the approximate time accepted as the completion of the Great Pyramid of Giza, the oldest pyramid of the Giza Plateau.

- 2400 BCE – 2300 BCE: The first of the oldest surviving religious texts, the Pyramid Texts, was composed in Ancient Egypt.[19][20]

- 2200 BCE: The Minoan civilization developed in Crete. Citizens worshipped a variety of goddesses.

- 2150–2000 BCE: The earliest surviving versions of the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh—originally titled He who Saw the Deep (Sha naqba īmuru) or Surpassing All Other Kings

(Shūtur eli sharrī)—were written.

- 1800 BC Birth of Abraham following the foundation of Judaism and the Abrahamic religions

- 1600 BCE: The ancient development of Stonehenge came to an end.

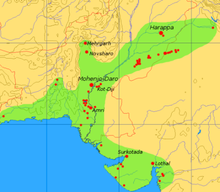

- 1500 BCE: The Vedic period began in India after the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilisation.

- 1500 BCE – 1000 BCE: The oldest of the Hindu Vedas (scriptures), the Rigveda was composed.[21][22][23] This is the first mention of Rudra, a fearsome form of Shiva as the supreme god.

- 1353 BCE or 1351 BCE: The beginning of the reign of Akhenaten, sometimes credited with starting the earliest known recorded monolatristic religion, in Ancient Egypt.[24][25]

- 1300 BCE – 1046 BCE: The polytheistic religion of the Chinese Shang dynasty reached its mature form.

- 1300 BCE – 1000 BCE: The "standard" Akkadian version of the Epic of Gilgamesh was edited by Sîn-lēqi-unninni.[26]

- 1200 BCE: The Greek Dark Age began.[27]

- 1200 BCE: The Olmecs built the earliest pyramids and temples in Central America.[28]

- 877 BCE – 777 BCE: The life of Parshvanatha, 23rd Tirthankara of Jainism.[29][30]

- 800 BCE – 300 BCE: The Upanishads (Vedic texts) were composed, containing the earliest emergence of some of the central religious concepts of Hinduism and Buddhism.

- 800 BCE: The Greek Dark Age ends.[31][32]

- 8th to 6th centuries BCE: The Chandogya Upanishad is compiled, significant for containing the earliest to date mention of Krishna. Verse 3.17.6 mentions Krishna Devakiputra (Sanskrit: कृष्णाय देवकीपुत्रा) as a student of the sage Ghora Angirasa.

- 5th centuries BCE: The first five books of the Jewish Tanakh, the Torah (Hebrew: תורה), are probably compiled.[33]

- 6th century BCE: Possible start of Zoroastrianism;[34] Zoroastrianism flourished under the Persian emperors known as the Achaemenids. The emperors Darius (ruled 522–486 BCE) and Xerxes (ruled 486–465 BCE) made it the official religion of their empire.[35]

- 600 BCE – 500 BCE: The earliest Confucian writing, Shu Ching, incorporates ideas of harmony and heaven.

- 599 BCE – 527 BCE: The life of Mahavira, 24th and last Tirthankara of Jainism.[36]

- c. 570 BCE: Pythagoras, founder of Pythagoreanism, was born.

- 563 BCE – 400 BCE: Siddharta Gautama, founder of Buddhism, was born.[37][38][39]

- 515 BCE – 70 CE: Second Temple period. The synagogue and Jewish eschatology can all be traced back to the Second Temple period.

- 551 BCE: Confucius, founder of Confucianism, was born.[28]

- 447 BCE: The Parthenon is dedicated to the goddess Athena.

- 399 BCE: Socrates was tried for impiety.

- 369 BCE – 372 BCE: Birth of Mencius and Zhuang Zhou.

- 300 BCE: The oldest known version of the Tao Te Ching was written on bamboo tablets.[40]

- 300 BCE: Theravada Buddhism was introduced to Sri Lanka by the Venerable Mahinda.[citation needed]

- c. 250 BCE: The Third Buddhist council was convened by Ashoka. Ashoka sends Buddhist missionaries to faraway countries, such as China, mainland Southeast Asia, Malay kingdoms, and Hellenistic kingdoms.

- c. 200 BCE: Worship of Yahweh's consort Asherah ends in Israel.

- 140 BCE: The earliest grammar of Sanskrit literature was composed by Pāṇini.[41]

- 140 BCE – 200 CE: The Development of the Hebrew Bible canon.

- 100 BCE – 500 CE: The Yoga Sūtras of Patanjali, one of the oldest texts in Yoga, were composed.

Common Era (CE)

[edit]1st to 5th centuries

[edit]- 6 BCE – 33 CE: The life of Jesus of Nazareth, the central figure of Christianity.

- 8 CE: Ovid's Metamorphoses chronicles the history of the world from its creation to the deification of Julius Caesar.

- 27 CE – 31 CE: The death of John the Baptist.

- 12 CE – 38 CE: According to the Haran Gawaita, Nasoraean Mandaean disciples of John the Baptist flee persecution in Jerusalem and arrive in Media during the reign of a Parthian king identified as Artabanus II who ruled between 12 and 38 CE.[42][43]: IX

- 50 CE – 62 CE: The first Christian Council was convened in Jerusalem.

- 55 - 90 CE: The gospel of Mark is written, (55-62) Gospels of Luke and Mathew are written. John is written later, likely towards the end of his life.

- 70 CE: The Siege of Jerusalem, the Destruction of the Temple, and the rise of Rabbinic Judaism.

- 150 – 250: Nagarjuna, Indian Mahayana Buddhist, philosopher and founder of Madhyamaka-Sunyavada Buddhism

- 200: Some of the oldest parts of the Ginza Rabba, a core text of Mandaeism, were written.

- 216: Mani, founder and prophet of Manichaeism, is born.

- 250 – 900: Classic Mayan step pyramids were constructed.

- 313: The Edict of Milan decreed religious toleration in the Roman empire.

- 325: The first ecumenical council (the Council of Nicaea) was convened to attain a consensus on doctrine through an assembly representing all Christendom. It established the original Nicene Creed and fixed the date of Easter. It also confirmed the primacy of the Sees of Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, and granted the See of Jerusalem a position of honour.

- c. 350: The oldest record of the complete biblical texts (the Codex Sinaiticus) survives in a Greek translation called the Septuagint, dating to the 4th century CE.

- 380: Theodosius I declared Nicene Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire.

- 381: The second ecumenical council (the First Council of Constantinople) reaffirmed and revised the Nicene Creed, repudiating Arianism and Pneumatomachi.

- 381 – 391: Theodosius outlaws paganism within the Roman Empire. Laws enacted requiring death penalty for acts of Divination.

- 393: A council of early Christian bishops listed and approved a biblical canon for the first time at the Synod of Hippo.

- 400: Saint Augustine exhorts his congregation to smash all pagan artefacts, saying "for that all superstition of pagans and heathens should be annihilated is what God wants, God commands, God proclaims!"

Middle Ages (5th–15th centuries)

[edit]5th to 10th centuries

[edit]- 405: Jerome completed the Vulgate, the first Latin translation of the Bible.

- 410: The Western Roman Empire began to decline, signalling the onset of the Middle Ages.

- 424: The Church of the East in Sasanian Empire (Persia) formally separated from the See of Antioch and proclaimed full ecclesiastical independence.

- 431: The third ecumenical council (the First Council of Ephesus) was convened as a result of the controversial teachings of Nestorius of Constantinople. It repudiated Nestorianism, proclaimed the Virgin Mary as the Theotokos (the God-bearer or Mother of God). It also repudiated Pelagianism and again reaffirmed the Nicene Creed.

- 449: The Second Council of Ephesus declared support for Eutyches and attacked his opponents. Originally convened as an ecumenical council, its ecumenical nature was rejected by the Chalcedonians, who denounced the council as latrocinium.

- 451: The fourth ecumenical council (the Council of Chalcedon) rejected the Eutychian doctrine of monophysitism, adopting instead the Chalcedonian Creed. It reinstated those deposed in 449, deposed Dioscorus of Alexandria and elevated the bishoprics of Constantinople and Jerusalem to the status of patriarchates.

- 451: The Oriental Orthodox Church rejected the Christological view put forth by the Council of Chalcedon and was excommunicated.

- 480 – 547: Benedict of Nursia wrote his Rule, laying the foundation of Western Christian monasticism.

- 553: The fifth ecumenical council (the Second Council of Constantinople) repudiated the Three Chapters as Nestorian and condemned Origen of Alexandria.

- 570 – 632: The life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

- 632: Work began on the compilation of the Quran into the form of a book (soon to be known as Mashaf-ul-Hafsa), in the era of Abu Bakr, the first Caliph of Islam.

- 632 – 661: The Rashidun Caliphate heralded the Arab conquest of Persia, Egypt and Iraq, bringing Islam to those regions.

- 661 – 750: The Umayyad Caliphate brought the Arab conquest of North Africa, Spain and Central Asia, marking the greatest extent of the Arab conquests and bringing Islam to those regions.

- 680 – 681: The sixth ecumenical council (the Third Council of Constantinople) rejected Monothelitism and Monoenergism.

- c. 680: The division between Sunni Islam and Shia Islam developed.[citation needed]

- 692: The Quinisext Council (also known as the Council in Trullo), an amendment to the 5th and 6th ecumenical councils, established the Pentarchy.

- 712: The Kojiki, the oldest Shinto text, was written.[28]

- 754: The latrocinium Council of Hieria supported iconoclasm.

- 787: The seventh ecumenical council (the Second Council of Nicaea) restored the veneration of icons and denounced iconoclasm.

- 788 – 820: The life of Hindu philosopher Adi Shankara, who consolidated the doctrine of Advaita Vedanta.

- c. 850: The oldest extant manuscripts of the vocalised Masoretic text, upon which modern editions are based, date to 9th century CE.[citation needed]

11th to 15th centuries

[edit]- 1017 – 1137: Life of the founder of Vishishtadvaita Vedanta, philosopher and social reformer Ramanuja

- c. 1052 – c. 1135: The life of Milarepa, one of the most famous yogis and poets of Tibetan Buddhism.

- 1054: The Great Schism between the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches was formalised.

- 1095 – 1099: The First Crusade led to the capture of Jerusalem.

- 1107 – 1110: Sigurd I of Norway led the Norwegian Crusade against Muslims in Spain, the Balearic Islands and in Palestine.

- 1147 – 1149: The Second Crusade was waged in response to the fall of the County of Edessa.

- 1189 – 1192: In the Third Crusade European leaders attempted to reconquer the Holy Land from Saladin.

- 1200: The earliest Mabinogion texts are compiled, cataloguing Celtic mythology in Middle Welsh.

- 1202 – 1204: The Fourth Crusade, originally intended to recapture Jerusalem, instead led to the sack of Constantinople, capital of the Byzantine Empire.

- 1206: The Delhi Sultanate was established.

- 1209 – 1229: The Albigensian Crusade was conducted to eliminate Catharism in Occitania, Europe.

- 1217 – 1221: With the Fifth Crusade, Christian leaders again attempted (but failed) to recapture Jerusalem.

- 1220: Snorri Sturluson authors the Prose Edda, cataloguing the beliefs of Norse Paganism.

- 1222 – 1282: The life of Nichiren Daishonin, the Buddha of the Latter Day of the Law and founder of Nichiren Buddhism. Based at the Nichiren Shoshu Head Temple Taisekiji (Japan), this branch of Buddhism teaches the importance of chanting the mantra Nam Myōhō Renge Kyō.

- 1228 – 1229: The Sixth Crusade won control of large areas of the Holy Land for Christian rulers, more through diplomacy than through fighting.

- 1229: The Codex Gigas was completed by Herman the Recluse in the Benedictine monastery of Podlažice near Chrudim.

- 1238 – 1317: Life of philosopher Madhvacharya, founder of Dvaita Vedanta

- 1244: Jerusalem was sacked again, instigating the Seventh Crusade.

- 1270: The Eighth Crusade was launched by Louis IX of France but largely petered out when Louis died shortly after reaching Tunis.

- 1271 – 1272: The Ninth Crusade failed.

- 1300 – 1521: During the Aztecs' existence in the post-classic period from 1300 to 1521, they practised a religion which encompassed a complex range of practices and beliefs, being generally polytheistic. Human sacrifice was practised on a grand scale throughout the Aztec Empire, which was performed in honour of their gods.[44]

- 1320: Pope John XXII laid the groundwork for future witch-hunts with the formalisation of the persecution of witchcraft.

- 1378 – 1417: The Roman Catholic Church split during the Western Schism.

- 1415: The death of Jan Hus who is considered as the first reformer of the Western Christianity. This event is often considered as the beginning of the Reformation.[45][46]

- 1469 – 1539: The life of Guru Nanak, founder of Sikhism.

- 1484: Pope Innocent VIII marked the beginning of the classical European witch-hunts with his papal bull Summis desiderantes.

- 1486 – 1534: Chaitanya Mahaprabhu popularised the chanting of the Hare Krishna and composed the Shikshashtakam (eight devotional prayers) in Sanskrit. His followers, Gaudiya Vaishnavas, revere him as a spiritual reformer, a Hindu revivalist and an avatar of Krishna.

Early modern and Modern eras

[edit]16th century

[edit]- 1500: In the Spanish Empire, Catholicism was spread and encouraged through such institutions as the missions and the Inquisition.

- 1517: Martin Luther posted The Ninety-Five Theses on the door of All Saints' Church, Wittenberg, launching the Protestant Reformation.

- 1526: African religious systems were introduced to the Americas, with the commencement of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

- 1534: Henry VIII separated the English Church from Rome and made himself Supreme Head of the Church of England.[47]

- 1562: The Massacre of Vassy sparked the first of a series of French Wars of Religion.[48][49]

17th century

[edit]- 1674: Chatrapati Shivaji Maharaj became 1st Chatrapati of Maratha Kingdom

- 1699: Guru Gobind Singh Ji created the Khalsa in Sikhism.[50]

18th century

[edit]- 1708: Guru Gobind Singh, the last Sikh guru, died after instituting the Sikh holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib, as the eternal Guru.

- 1770: Baron d'Holbach published The System of Nature said to be the first positive, unambiguous statement of atheism in the West.[51]

- 1781: Ghanshyam, later known as Sahajanand Swami/Swaminarayan, was born in Chhapaiya at the house of Dharmadev and Bhaktimata.

- 1789 – 1799: in the Dechristianisation of France[52][53] the Revolutionary Government confiscated Church properties, banned monastic vows and, with the passage of the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, removed control of the Church from the Pope and subordinated it as a department of the Government. The Republic also replaced the traditional Gregorian Calendar and abolished Christian holidays.

- c. 1790 – 1840: The Second Great Awakening, a Protestant religious revival in the United States.

- 1791: Freedom of religion, enshrined in the Bill of Rights, was added as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, forming an early and influential secular government.

- 1794: the Cult of the Supreme Being in France is founded by Maximilien Robespierre.[54]

19th century

[edit]- 1801: the French Revolutionary Government and Pope Pius VII entered into the Concordat of 1801. While Roman Catholicism regained some powers and became recognised as "the religion of the great majority of the French", it was not afforded the latitude it had enjoyed prior to the Revolution and was not re-established as the official state religion. The Church relinquished all claims to estate seized after 1790, the clergy was state salaried and was obliged to swear allegiance to the State. Religious freedom was restored.

- 1819 – 1850: The life of Siyyid 'Alí Muḥammad Shírází (Persian: سيد علی محمد شیرازی), better known as the Báb, the founder of Bábism.

- 1817 – 1892: The life of Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Baháʼí Faith.

- 1823: Joseph Smith claims to receive visions and golden plates to be translated as the Book of Mormon.

- 1830s: Adventism was started by William Miller in the United States.[55]

- 1830: the Church of Christ was founded by Joseph Smith on 6 April – initiating the Latter Day Saint restorationist movement.

- 1835 – 1908: the life of Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, the founder of the Ahmadiyya Movement.

- 1836 – 1886: the life of Ramakrishna, saint and mystic of Bengal.

- 1844: Joseph Smith was murdered, reportedly by John C. Elliott,[56] on 27 June, resulting in a succession crisis in the Latter Day Saint movement.

- 1857: first great popular uprising against British colonial government in India. Also called Indian Rebellion of 1857.

- 1875: the Theosophical Society was formed in New York City by Helena Blavatsky, Henry Steel Olcott, William Quan Judge and others.

- 1879: Christian Science was granted its charter in Boston, Massachusetts.

- 1881: Zion's Watch Tower Tract Society was formed by Charles Taze Russell, initiating the Bible Student movement.

- 1889: the Ahmadiyya Community was established.

- 1893: Swami Vivekananda's first speech at The Parliament of the World's Religions, Chicago, brought the ancient philosophies of Vedanta and Yoga to the western world.

- 1899: Aradia (aka The Gospel of the Witches), one of the earliest books describing post witchhunt European religious Witchcraft, was published by Charles Godfrey Leland.[57]

20th century

[edit]- 1901: The incorporation of the Spiritualists' National Union legally representing Spiritualism in the United Kingdom.

- 1904: Thelema was founded by Aleister Crowley.[58]

- 1905: In France the law on the Separation of the Churches and the State was passed, officially establishing state secularism and putting an end to the funding of religious groups by the state.[59]

- 1907: Formation of BAPS (Bochasanwasi Shri Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha), a major sect in the Swaminarayan Sampradaya by Shastriji Maharaj

- 1908: The Khalifatul Masih was established in the Ahmadiyya Muslim Community as the "Second Manifestation of God's Power".

- 1913: The Moorish Science Temple of America is founded in Newark, New Jersey.

- 1917: The October Revolution in Russia led to the annexation of all church properties and subsequent religious suppression.[citation needed]

- 1920: The Self-Realization Fellowship Church of all Religions with its headquarters in Los Angeles, CA, was founded by Paramahansa Yogananda.

- 1922 – 1991: Persecution of Christians in the Soviet Union. The total number of Christian victims under the Soviet regime has been estimated to range around 12 to 20 million.

- 1926: Cao Dai founded.

- 1929: The Cristero War, fought between the secular government and religious Christian rebels in Mexico, ended.

- 1930: The Rastafari movement began following the coronation of Haile Selassie I as Emperor of Ethiopia.

- 1930: After previously failing to claim the leadership of the Moorish Science Temple of America, Wallace Fard Muhammad creates the Nation of Islam in Detroit, Michigan.

- 1931: Jehovah's Witnesses emerged from the Bible Student movement under the influence of Joseph Franklin Rutherford.[60]

- 1932: A neo-Hindu religious movement, the Brahma Kumaris or "Daughters of Brahma", started. Its origin can be traced to the group "Om Mandali", founded by Lekhraj Kripalani (1884–1969).

- 1939 – 1945: Millions of Jews were relocated and murdered by the Nazis during the Holocaust.

- 1947: Pakistan, the first nation-state in the name of Islam was created. British India was partitioned into the secular nation of India with a Hindu majority and the Muslim-majority nation of Pakistan (the eastern half of whom would later become Bangladesh).

- 1948: The modern state of Israel was established as a homeland for the Jews.

- 1954: The Church of Scientology was founded by L. Ron Hubbard.[61]

- 1954: Wicca was publicised by Gerald Gardner.[62]

- 1955: The Urantia Book was published by the Urantia Foundation.[63]

- 1956: Navayana Buddhism (Neo-Buddhism) was founded by B. R. Ambedkar, initially attracting some 380,000 Dalit converts from Hinduism.

- 1959: The 14th Dalai Lama fled Tibet amidst unrest and established an exile community in India.

- 1960s: Various Neopagan and New Age movements gained momentum.[vague][citation needed]

- 1961: Unitarian Universalism was formed from the merger of Unitarianism and Universalism.[64]

- 1962: The Church of All Worlds, the first American neo-pagan church, was formed by a group including Oberon Zell-Ravenheart, Morning Glory Zell-Ravenheart, and Richard Lance Christie.

- 1962 – 1965: The Second Vatican Council was convened.[65][66][67][68]

- 1965: Srila Prabhupada established the International Society for Krishna Consciousness and introduced translations of the Bhagavad-Gita and Vedic scriptures in mass production all over the world.

- 1966: The Church of Satan was founded by Anton LaVey on Walpurgisnacht.[69]

- 1972 – 1984: The Stonehenge free festivals started.[70]

- 1972 – 2004: Germanic Neopaganism (aka Heathenism, Heathenry, Ásatrú, Odinism, Forn Siðr, Vor Siðr, and Theodism) began to experience a second wave of revival.[71][72][73][74][75]

- 1973: Claude Vorilhon established the Raëlian Movement and changed his name to Raël following a purported extraterrestrial encounter in December 1973.

- 1975: The Temple of Set was founded in Santa Barbara, California.

- 1979: The Iranian Revolution resulted in the establishment of an Islamic Republic in Iran.[76]

- 1981: The Stregherian revival continued. "The Book of the Holy Strega" and "The Book of Ways", Volumes I and II, were published.

- 1984: Operation Blue Star in the holiest site of the Sikhs, the Golden Temple in Amritsar, led to Anti-Sikh riots in Delhi and adjoining regions, following the assassination of Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

- 1985: The Battle of the Beanfield forced an end to the Stonehenge free festivals.[70][77][78]

- 1989: Following the revolutions of 1989, the overthrow of many Soviet-style states allowed a resurgence in open religious practice in many Eastern European countries.[79]

- 1990s: Reconstructionist Pagan movements (Celtic, Hellenic, Roman, Slavic, Baltic, Finnish, etc.) proliferate throughout Europe.

- 1993: The European Council convened in Copenhagen, Denmark, agreed to the Copenhagen Criteria, requiring religious freedom within all members and prospective members of the European Union.[80]

- 1993: The World Union of Deists is founded in the United States.[81]

- 1995: First Traditional Hindu Mandir outside of India created in London by Pramukh Swami Maharaj (1921–2016) Guru of BAPS.

- 1998: The Strega Arician Tradition was founded.[82]

21st century

[edit]- 2002: Joy of Satan Ministries was founded by Andrea Dietrich following her conception of the ideology of "spiritual Satanism".[83]

- 2005: Becoming a place of pilgrimage for neo-druids and other pagans, the Ancient Order of Druids organised the first recorded reconstructionist ceremony in Stonehenge in 2005.[84]

- 2006: Sectarian rivalries exploded in Iraq between Sunni Muslims and Shias, with each side targeting the other in terrorist acts, and bombings of mosques and shrines.[85]

- 2008: Nepal, the world's only Hindu Kingdom, was declared a secular state by its Constituent Assembly after declaring the state a Republic on 28 May 2008.[86]

- 2009: The Church of Scientology in France was fined €600,000 and several of its leaders were fined and imprisoned for defrauding new recruits of their savings.[87][88][89] The state failed to disband the church owing to legal changes occurring over the same time period.[89][90]

- 2011: Civil war broke out in Syria over domestic political issues. The country soon split along sectarian lines between Sunni Muslims, Alawite and Shiites.[91] War crimes and acts of genocide were committed by both parties as religious leaders on each side condemned the other as heretics.[92] The Syrian civil war soon became a battleground for regional sectarian unrest, as fighters joined the fight from as far away as North America and Europe, as well as Iran and the Arab states.[93]

- 2013: The Satanic Temple was founded by Lucien Greaves and Malcolm Jarry (pseudonyms).

- 2014: A supposed Islamic Caliphate was established by the self-proclaimed Islamic State in regions of war torn Syria and Iraq, drawing global support from radical Sunni Muslims.[94][95] This was a modern-day attempt to re-establish Islamic self-rule in accordance with strict adherence to Shariah-Islamic religious law.[96] In the wake of the Syrian civil war, Islamic extremists targeted the indigenous Arab Christian communities. In acts of genocide, numerous ancient Christian and Yazidi communities were evicted and threatened with death by various Muslim Sunni fighter groups.[97] After ISIS terrorist forces infiltrated and took over large parts of northern Iraq from Syria, many ancient Christian and Yazidi enclaves were destroyed.[97][98]

- 2019: The Orthodox Church of Ukraine is granted independence from the Russian Orthodox Church by the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople.[99]

See also

[edit]- Axial Age

- Evolutionary origin of religion

- History of religion

- Holocene calendar

- Chibanian

- Paleolithic religion

- Prehistoric religion

- Religion and mythology

- Late Pleistocene

Notes

[edit]- ^ "Historic writing". British Museum. Retrieved 4 May 2016.

- ^ Wunn, Ina (2000). "Beginning of Religion" (PDF). Numen. 47 (4): 417–452. doi:10.1163/156852700511612. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 August 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f Pettitt, Paul (August 2002). "When Burial Begins". British Archaeology. No. 66. Archived from the original on 2 June 2007.

- ^ Bowler JM, Jones R, Allen H, Thorne AG (1970). "Pleistocene human remains from Australia: a living site and human cremation from Lake Mungo, Western New South Wales". World Archaeol. 2 (1): 39–60. doi:10.1080/00438243.1970.9979463. PMID 16468208.

- ^ Barbetti M, Allen H (1972). "Prehistoric man at Lake Mungo, Australia, by 32,000 years BP". Nature. 240 (5375): 46–8. Bibcode:1972Natur.240...46B. doi:10.1038/240046a0. PMID 4570638. S2CID 4298103.

- ^ Bowler, J.M. 1971. Pleistocene salinities and climatic change: Evidence from lakes and lunettes in southeastern Australia. In: Mulvaney, D.J. and Golson, J. (eds), Aboriginal Man and Environment in Australia. Canberra: Australian National University Press, pp. 47–65.

- ^ Bowler JM, Johnston H, Olley JM, Prescott JR, Roberts RG, Shawcross W, Spooner NA (2003). "New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia". Nature. 421 (6925): 837–40. Bibcode:2003Natur.421..837B. doi:10.1038/nature01383. PMID 12594511. S2CID 4365526.

- ^ Olleya JM, Roberts RG, Yoshida H, Bowler JM (2006). "Single-grain optical dating of grave-infill associated with human burials at Lake Mungo, Australia". Quaternary Science Reviews. 25 (19–20): 2469–2474. Bibcode:2006QSRv...25.2469O. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2005.07.022.

- ^ "Images for Chapter 20 Hominids". ucdavis.edu. Archived from the original on 19 May 2008.

- ^ Bailey, Martin (31 January 2013). "Ice Age Lion Man is the world's earliest figurative sculpture". The Art Newspaper. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Kenoyer, J. M.; Clark, J. D.; Pal, J. N.; Sharma, G. R. (1 July 1983). "An upper palaeolithic shrine in India?" (PDF). Antiquity. 57 (220): 88–94. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00055253. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 163969200.

- ^ Som, Adheer (2023). "Baghor Kali: The timeless roots of Sanatana Dharma". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 November 2023.

- ^ "The World's First Temple", Archaeology magazine, Nov/Dec 2008 p 23.

- ^ "Material Worlds: Art and Agency in the Near East and Africa".

- ^ Rollefson, Gary O (January 2002). "Ritual and Social Structure at Neolithic 'Ain Ghazal". In Kujit, Ian (ed.). Life in Neolithic Farming Communities: Social Organization, Identity, and Differentiation. New York, New York: Springer. p. 185. ISBN 9780306471667.

- ^ "Beginning in the pottery-phase of the Neolithic, clay tokens are widely attested as a system of counting and identifying specific amounts of specified livestock or commodities. The tokens, enclosed in clay envelopes after being impressed on their rounded surface, were gradually replaced by impressions on flat or plano-convex tablets, and these in turn by more or less conventionalized pictures of the tokens incised on the clay with a reed stylus. The transition to writing was complete W. Hallo; W. Simpson (1971). The Ancient Near East. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. p. 25.

- ^ "PlanetQuest: The History of Astronomy – Newgrange".

- ^ A History of Ancient Egypt: From the First Farmers to the Great Pyramid, John Romer, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Shaw, Ian, ed. (2002). The Oxford history of ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- ^ Allen, James P.; Der Manuelian, Peter, eds. (2005). The ancient Egyptian pyramid texts. Writings from the ancient world. Atlanta: Soc. of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-182-7.

- ^ Flood, Gavin D. (1996). An Introduction to Hinduism. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse The Wheel And Language. How Bronze-Age Riders From the Eurasian Steppes Shaped The Modern World. Princeton University Press.

- ^ Thapar, Romila; Witzel, Michael; Menon, Jaya; Friese, Kai; Khan, Razib (2019). Which of us are Aryans? rethinking the concept of our origins. New Delhi: Aleph. ISBN 978-93-88292-38-2.

- ^ Montserat, Dominic (2003). Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt (1st paperback ed.). London, UK; New York, NY: Routledge (published 2000). p. 36. ISBN 0415301866.

- ^ Dorman, Peter F. (22 April 2024). "Akhenaton (King of Egypt)". Britannica.com. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ The Epic of Gilgamesh. Translated by Andrew R. George (reprinted ed.). London: Penguin Books. 2003 [1999]. pp. ii, xxiv–v. ISBN 0-14-044919-1.

The Babylonians believed this poem to have been the responsibility of a man called Sîn-liqe-unninni, a learned scholar of Uruk whom modern scholars consider to have lived some time between 1300–1000 BC.

- ^ Knodell, Alex R. (2021). Societies in Transition in Early Greece: An Archaeological History. Oakland, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-5203-8053-0.

- ^ a b c Smith, Laura (2007). Illustrated Timeline of Religion. Sterling Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4027-3606-3.

- ^ Fisher 1997, p. 115.

- ^ "Parshvanatha". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 2007. Retrieved 22 October 2007.

- ^ "The History of Greece". Hellenicfoundation.com. Archived from the original on 7 December 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2024.: "The period from 1100 to 800 B.C. is known as the Dark Age of Greece. As described in the Ancient Greek Thesaursus: Throughout the area there are signs of a sharp cultural decline. Some sites, formerly inhabited, were now abandoned."

- ^ Martin, Thomas R., (October 3, 2019). "The Dark Ages of Ancient Greece" Archived 2020-10-26 at the Wayback Machine: "...The Near East recovered its strength much sooner than did Greece, ending its Dark Age by around 900 B.C...The end of the Greek Dark Age is traditionally placed some 150 years after that, at about 750 B.C..." Retrieved October 24, 2020

- ^ Old Testament Canon, Texts, and Versions. Encyclopaedia Britannica. 16 August 2024.

- ^ Nigosian, S. A.; Nigosian, Solomon Alexander (1993). The Zoroastrian Faith: Tradition and Modern Research. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 3. ISBN 978-0-7735-1144-6.

- ^ The Encyclopedia of World Religions (Revised ed.). DWJ Books. 2007.

- ^ "Mahavira." Britannica Concise Encyclopedia. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 2006. Answers.com 28 November 2009. http://www.answers.com/topic/mahavira

- ^ Rawlinson, Hugh George. (1950) A Concise History of the Indian People, Oxford University Press. p. 46.

- ^ Muller, F. Max. (2001) The Dhammapada And Sutta-nipata, Routledge (UK). p. xlvii. ISBN 0-7007-1548-7.

- ^ India: A History. Revised and Updated, by John Keay: "The date [of Buddha's meeting with Bimbisara] (given the Buddhist 'short chronology') must have been around 400 BCE."

- ^ Chan, Alan (21 September 2018). "Laozi". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 3 August 2024.

- ^ Ashtadhyayi, Work by Panini. Encyclopædia Britannica. 2013. Archived from the original on 5 August 2017. Retrieved 23 October 2017.

Ashtadhyayi, Sanskrit Aṣṭādhyāyī ("Eight Chapters"), Sanskrit treatise on grammar written in the 6th to 5th century BCE by the Indian grammarian Panini.

- ^ Buckley, Jorunn Jacobsen (2010). Turning the Tables on Jesus: The Mandaean View. In Horsley, Richard (March 2010). Christian Origins. Fortress Press. ISBN 9781451416640.(pp94-111). Minneapolis: Fortress Press

- ^ Drower, Ethel Stefana (1953). The Haran Gawaita and the Baptism of Hibil-Ziwa. Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana.

- ^ Ingham, John M. "Human Sacrifice at Tenochtitlan"

- ^ "Jan Hus – Bohemian religious leader". 30 April 2024.

- ^ "Jan Hus". 11 June 2014.

- ^ Liles, Jessie. "The Marriage of Power and Reform in Henry VII's Act of Supremacy, 1534". ProQuest. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ Pettegree, Andrew. "The Reformation World". Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ "Act of Supremacy". Britannica. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur. "The Birth of the Khalsa: A Feminist Re-Memory of Sikh Identity". State University of New York Press. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ Jonathan Miller in Atheism: A Rough History of Disbelief

- ^ Tallet, Frank Religion, Society and Politics in France Since 1789 p. 1, 1991 Continuum International Publishing

- ^ Tallet, Frank Religion, Society and Politics in France Since 1789 p. 2, 1991 Continuum International Publishing

- ^ Alpaugh, Micah (2021). The French Revolution: A History in Documents. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 181. ISBN 978-1-350-06531-4.

- ^ Mead, Frank S; Hill, Samuel S; Atwood, Craig D (1975). "Adventist and Sabbatarian (Hebraic) Churches". Handbook of Denominations in the United States (12th ed.). Nashville: Abingdon Press. pp. 256–76. ISBN 9780687165698.

- ^ Cone, Stephen (1896). Biographical and historical sketches; a narrative of Hamilton and its residents from 1792 to 1896. Hamilton, Ohio: Republican Publishing Company. p. 184.

- ^ Clifton, Chas (1998). "The Significance of Aradia". in Mario Pazzaglini. Aradia, or the Gospel of the Witches, A New Translation. Blaine, Washington: Phoenix Publishing, Inc.. p. 73. ISBN 0-919345-34-4.

- ^ Lingan, Edmund B. (2014). Aleister Crowley's Thelemic Theatre. pp. 101–130. doi:10.1057/9781137448613_5. ISBN 978-1-349-49727-0. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ "100th Anniversary of Secularism in France". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 9 December 2005.

- ^ Leo P. Chall, Sociological Abstracts, vol 26 issues 1–3, "Sociology of Religion", 1978, p. 193 col 2: "Rutherford, through the Watch Tower Society, succeeded in changing all aspects of the sect from 1919 to 1932 and created —a charismatic offshoot of the Bible student community."

- ^ "What is Scientology and who was L. Ron Hubbard?". The Telegraph. 6 October 2016. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 3 January 2018.

- ^ Gardner, Gerald B (1999) [1954]. Witchcraft Today. Lake Toxaway, NC: Mercury Publishing. OCLC 44936549

- ^ Gooch, Brad (2002). Godtalk: Travels in Spiritual America. A.A. Knopf. p. 34. ISBN 9780679447092.

- ^ "About Oberon Zell". 24 November 2007. Archived from the original on 24 November 2007.

- ^ Faculty of Catholic University of America, ed (1967). "Vatican Council II". New Catholic Encyclopedia. XIV (1 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 563. OCLC 34184550.

- ^ Alberigo, Giuseppe; Sherry, Matthew (2006). A Brief History of Vatican II. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. pp. 69. ISBN 1-57075-638-4.

- ^ Hahnenberg, Edward (2007). A Concise Guide to the Documents of Vatican II. City: Saint Anthony Messenger Press. pp. 44. ISBN 0-86716-552-9.

- ^ Alberigo, Giuseppe; Sherry, Matthew (2006). A Brief History of Vatican II. Maryknoll: Orbis Books. pp. 1. ISBN 1-57075-638-4.

- ^ The Church of Satan: A History of the World's Most Notorious Religion by Blanche Barton (Hell's Kitchen Productions, 1990, ISBN 0-9623286-2-6)

- ^ a b McKay, George (1996) Senseless Acts of Beauty: Cultures of Resistance since the Sixties, ch.1 'The free festivals and fairs of Albion', ch. 2 two 'O life unlike to ours! Go for it! New Age travellers'. London: Verso. ISBN 1-85984-028-0

- ^ Icelandic, "Hugmyndin að Ásatrúarfélaginu byggðist á trú á dulin öfl í landinu, í tengslum við mannfólkið sem skynjaði ekki þessa hluti til fulls nema einstöku menn. Það tengdist síðan þjóðlegum metnaði og löngun til að Íslendingar ættu sína trú, og ræktu hana ekki síður en innflutt trúarbrögð." Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson (1992:140).

- ^ "Fyrirspurnartími". Morgunblaðið, 27 November 1973.

- ^ Ólafur Jóhannesson. Stjórnskipun Íslands. Hlaðbúð, 1960. Page 429.

- ^ Icelandic, "fór fram með tilþrifum og atorku", "Reiddust goðin?" Vísir, 7 August 1973.

- ^ ÞS. "Blótuðu Þór í úrhellisrigningu." Vísir, 7 August 1973.

- ^ "Iran 1979: the Islamic revolution that shook the world". Al Jazeera. 11 February 2024. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ Ed. Andy Worthington, 2005, The Battle of the Beanfield, Enabler Publications, ISBN 0-9523316-6-7

- ^ Hippies clash with police at Stonehenge (1985), BBC News archive Accessed 22 January 2008.

- ^ E. Szafarz, "The Legal Framework for Political Cooperation in Europe" in The Changing Political Structure of Europe: Aspects of International Law, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 0-7923-1379-8. p.221.

- ^ Lassen, Eva Maria (23 April 2020). "Limitations to Freedom of Religion or Belief in Denmark". Religion & Human Rights. 15 (1–2): 134–152. doi:10.1163/18710328-BJA10008. Retrieved 22 September 2024.

- ^ Hodge, Bodie; Patterson, Roger (2015). World Religions and Cults Volume 1: Counterfeits of Christianity. New Leaf Publishing. ISBN 9781614584605. Retrieved 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Arician tradition". Witchvox. Retrieved 7 February 2006.

- ^ Lewis, James (2016). The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements: Volume II. Oxford University Press; 2nd edition. p. 448. ISBN 978-0190466176.

- ^ Pearce, Q. L. (11 December 2009). Stonehenge. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-7377-5500-8. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ "Iraq War Timeline, 2006". infoplease.com.

- ^ George Conger (18 January 2008). "Nepal moves to become a secular republic". Religious Intelligence. Archived from the original on 30 January 2009.

- ^ Susan Sachs (27 October 2009). "Paris court convicts Scientology of fraud". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ "Scientologists convicted of fraud". BBC. 27 October 2009. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ a b Steven Erlanger (27 October 2009). "French Branch of Scientology Convicted of Fraud". New York Times. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ Devorah Lauter (27 October 2009). "French Scientology group convicted of fraud". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 October 2009.

- ^ "The Religious Component of the Syrian Conflict: More than Perception". georgetown.edu.

- ^ The Real News Network. "In Syria Both Sides Fear Annihilation If They Lay Down Arms". The Real News Network.

- ^ "20,000 foreign fighters flock to Syria, Iraq to join terrorists". cbsnews.com. 10 February 2015.

- ^ How ISIS Governs Its Caliphate(subscription required)

- ^ "One Year of the Islamic State Caliphate, Mapped". Foreign Policy. 16 May 2024.

- ^ "From Paper State to Caliphate: The Ideology of the Islamic State" (PDF).

- ^ a b "The Real War on Christianity". Foreign Policy. 16 May 2024.

- ^ Raya Jalabi (11 August 2014). "Who are the Yazidis and why is Isis hunting them?". the Guardian.

- ^ Paris, Francesca (5 January 2019). "Ukrainian Orthodox Church Officially Gains Independence From Russian Church". NPR. Retrieved 28 March 2023.

Bibliography

[edit]- Smith, Laura (2007), Illustrated Timeline of Religion, Sterling Publishing Company, ISBN 978-1-4027-3606-3

- Bowker, John (2006), World Religions, DK Pub., ISBN 0-7566-1772-3

- Sangave, Dr. Vilas Adinath (2001), Facets of Jainology: Selected Research Papers on Jain Society, Religion, and Culture, Mumbai: Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-81-7154-839-2

- Glasenapp, Helmuth Von (1999), Jainism, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-1376-2

- Fisher, Mary Pat (1997), Living Religions: An Encyclopedia of the World's Faiths, London: I.B.Tauris, ISBN 1-86064-148-2

- Deo, Shantaram Bhalchandra (1956), History of Jaina monachism from inscriptions and literature, Pune: Deccan College Post-graduate and Research Institute

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1952), Joseph Campbell (ed.), Philosophy of India, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd,

Not in copyright