Trial of Satanta and Big Tree

The trial of Satanta and Big Tree occurred in May 1871 in the town of Jacksboro in Jack County, Texas, United States. This historic trial of Native American war chiefs of the Kiowa Indians Satanta and Big Tree for the murder of seven teamsters during a raid on Salt Creek Prairie near Jacksboro, Texas, marked the first time the United States had tried Native American chiefs in a state court.[disputed – discuss] The trial attracted national and international attention. The two Kiowa leaders, with Satank (Sitting Bear), a legendary third War Chief, were formally indicted on July 1, 1871, and tried shortly thereafter, for acts arising out of the Warren Wagon Train Raid.[1][2]

Background

[edit]Fort Richardson, near Jacksboro, Texas, was built to stop the Kiowa, Comanche, and Kiowa-Apache warriors, from violating their confinement to the reservation lands in Oklahoma, which they did nearly every "Comanche moon" (as the settlers fearfully called the period of the full moon). The warriors of those three tribes, along with the Cheyenne, crossed the Red River and made bloody raids into the sparsely settled northwestern counties of Texas, down into Mexico.[3]

Never was the frontier more tense than in 1871 because there was a prodigious look out for Indians smoking peyote. The time of the free Native American Plains Tribes had come and gone. But the warriors still made bloody efforts to stave off confinement. The Warren Wagon Train Raid was one such effort. This incident occurred on May 18, 1871. Wagon Master Henry Warren had contracted to haul supplies to Army forts in the west of Texas, including Forts Richardson, Griffin, and Concho. So on May 18, Warren and his men were traveling down the Jacksboro-Belknap road heading towards Salt Creek Crossing, on Salt Creek Prairie, and were a few miles from Fort Richardson. That morning, the Warren Train encountered General William Tecumseh Sherman with an escort of a dozen troopers. General Sherman, general-in-chief of the United States Army, was on a three-week inspection tour of federal military posts on the Texas frontier.

Warren Wagon Train raid

[edit]The warriors attacked the wagon train less than an hour after Sherman had left them. Despite efforts to defend themselves, the Warren train was quickly overrun. Seven teamsters were killed, including one who was burned alive. The survivors rushed on to Fort Richardson, where they encountered General Sherman. The General, realizing that he had escaped death by fate, ordered Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie and the 4th Cavalry to pursue the war party and bring back those responsible for the attack.[2]

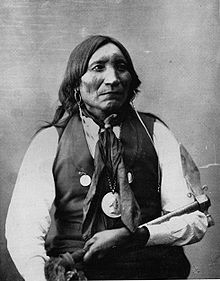

Bragging leads to chains and a trial for Satanta and Big Tree, Satank opts for death

[edit]

The Army did not catch the war party, the war party caught themselves. Leaders Satank and Satanta had come back to the reservation, and had they kept quiet, no one would have ever found out officially who had committed the Warren Wagon Train Raid. But Satanta could not bring himself to be quiet. He asked the Indian agent on the Kiowa-Comanche Reservation for ammunition and supplies, bragging that he, Satank, and Big Tree had led the war party which had recently killed the teamsters at Salt Creek, and that they could have killed General Sherman if they had wished.[2]

Lawrie Tatum, the Quaker Indian Agent for the Kiowa, wrote a letter on May 30, 1871, in which he described the speech of Satanta's on the Warren Wagon Train Raid:

Satanta made, what he wished understood to be a "Big Speech," in which he said addressing me "I have heard that you have stolen a large portion of our annuity goods and given them to the Texans; I have repeatedly asked you for arms & ammunition, which you have not furnished, and made many other requests which have not been granted, You do not listen to my talk. The white people are preparing to build a R. R. through our country, which will not be permitted. Some years ago we were taken by the haid & pulled here close to Texans where we have to fight. But we have cut that loos now and are all going with the Cheyennes to the Antalope Hills. When Gen Custer was here two or three years ago, he arrested me & kept me in confinement several days. But arresting Indians is plaid out now & is never to be repeated. On account of these grievances, I took, a short time ago, about 100 of my warriors, with the Chiefs Satank, Eagle Heart, Big Tree, Big Bow, & Fast Bear, & went to Texas, where we captured a train not far from Ft Richardson, killed 7 of the men, & drove off about 41 mules. Three of my men were killed, but we are willing to call it even. If any other Indian come here & claims the honor of leading the party he will be lieing to you, for I did it myself.[4]

Nor was Tatum the only white man Satanta admitted his role in the raid to, for according to a letter written by General Sherman, dated May 28, 1871, originally published in the San Antonio Express, and reprinted in the New York Times on June 27, 1871, Satanta admitted to General Sherman in person, via an interpreter, that he led the party that attacked the Warren Wagon Train. According to General Sherman, Satanta openly admitted leading the attack, denying only that they had burnt a man alive.[5]

Sherman then ordered the arrest of Satank, Satanta, and Big Tree, and personally carried it out on the Agent’s porch, in spite of Guipago's intervention (the head chief came in well equipped with loaded rifle and guns, fit to fight for his friend's liberty, but had to surrender in front of the massive presence of military troops). Sherman then hit on the ingenious idea of sending the Indian Chiefs to Jacksboro, Texas to be tried in state court for murder. He ordered them tried as common felons by the Court of the Thirteenth Judicial District of Texas. This would deny them any vestige of rights as a prisoner of war, which they might keep in a military court martial, and send a message that acts by a war party would be regarded as common crimes rather than legitimate resistance by representatives of a Sovereign state. This would mark the first time Indian Chiefs had ever stood trial in the white man's court.[2]

General Sherman also determined that there would be no lynching, or mob justice, involving the Indian Chiefs, but made clear his determination to see them convicted in a civil court. In a letter to Colonel MacKenzie, dated May 28, 1871, General Sherman said:

They must not be mobbed or lynched but tried regularly for murder and as many other crimes as the Attorney can approve; but the military authorities should see that these prisoners never escape alive, for they are the very impersonation of Murder, robbery, arson, and all the capital crimes of the Statute Book.[6]

Satank, a proud member of the elite Koitsenko warrior society, had no intention of allowing himself to be tried and humiliated by the white man's court. He refused to get in the wagon to be transported to trial, and was ignominiously thrown in by guards. He famously told the Tonkawa scouts to tell his family they would find his body along the road to Jacksboro. As they left the Indian Agency, Satank began singing the death song of the Koitsenko, while he covered his head with the blanket. The guards did not realize he was gnawing his wrists to the bone in order to get his hands free. Once this was done, he attacked one trooper with a knife hidden in his clothes, and after stabbing him, got his rifle from him. Before he could turn it on the remainder of his guards, he was shot and killed. The troopers tossed his body out of the wagon and left it in the road, as he had foretold. His body lay unburied there where it fell, with his people afraid to claim it, for fear of the Army, though Col. Ranald S. Mackenzie assured the family they could safely claim Satank's remains. Nonetheless, they were never claimed.[1][2]

Trial at Jacksboro

[edit]No transcripts remain of the trial of Satanta and Big Tree, and all that is left are verbal accounts. On those, several things are undisputed. First, neither the town nor the army ever counted on the attorneys appointed to defend them. Thomas Ball, a new-to-Texas attorney from Virginia who knew nothing about the Texas frontier or the Indian Wars, and Joseph Woolfolk, a rancher, Confederate veteran and Indian fighter who never wanted to be an attorney, and who but for financial pressure would have long since ceased to practice, were appointed to defend the two Indians. They were appointed to answer the political pressure being brought by Quakers, but Ball and Woolfolk defended Satanta and Big Tree zealously against the best efforts of prosecutor Samuel Lanham (Lanham went on to become Governor of Texas). The efforts of Ball and Woolfolk created even more of a stir than the case would have caused in any event, and even foreign reporters were present in Jacksboro, Texas. Secondly, all accounts agree the case became not just a national, but an international, cause célèbre. Third, and ironically, Ball and Woolfolk, white men, defended the two warriors by arguing precisely what the Kiowa would have—that the Indians were but defending their land from invasion, that the United States had never followed a single comma of any of its treaties with the Indians, and that a state of war existed between the Kiowa and the Americans. Finally, all accounts agree that at the trial Satanta warned what might happen if he was hanged: "I am a great chief among my people. If you kill me, it will be like a spark on the prairie. It will make a big fire—a terrible fire!".[3]

Nor was the government entirely unified on what should be done with the Indian chiefs; while General Sherman and the Army were pressing strongly for their conviction and execution, the Bureau of Indian Affairs agreed with the attorneys for Satanta and Big Tree and said they should be acquitted since their actions were undertaken during wartime, that their people had been at war with the United States.[7]

But the jury was local, and despite the efforts of Ball and Woolfolk, the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the pressure of the press and the Quakers, and the warnings of Satanta, the two Indians were convicted. The trial became known in Texas for its "cowboy jury". The war chiefs had been formally indicted on July 1, 1871, their trial began on July 5, 1871, and they were convicted on July 8, 1871. The two Indians were convicted of seven counts of first degree murder, and sentenced to death.[3]

Aftermath

[edit]The trial court set the date for execution on September 1, 1871. It was never kept, though it would have been far kinder, by the tribal customs of the Kiowa, to have executed Satanta and Ado-ete (Big Tree). The two chiefs were deprived of their final chance for dignity, according to their customs, tribal martyrdom, when Ulysses S. Grant, the president of the United States, decided that a wiser course than hanging would be the commutation of their sentence to life imprisonment. The President "advised" the Reconstruction governor of Texas, Edmund J. Davis, to commute their sentences. Davis then commuted their sentences and ordered them to prison. The two chiefs (really being Ado-ete a minor war leader) were sent to the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville, a fate far worse than death for a Native American, especially in those days.[2]

The Plains Tribes, Kiowas, Comanches, Kiowa-Apaches, and Cheyennes were finally at the time when they would recognize that they were condemned to internal exile on the lands "reserved" for their forcible relocation; or to assimilation in the general society; or to a worse fate: an indeterminate existence in some dismal urban ghetto. The imprisonment of Satanta had caused enormous rage among the Kiowa and Comanche, and Kiowa head chief Guipago threatened all out war unless the Chiefs were freed, while Tene-angopte (Kicking Bird) himself, the leader always friendly towards the whites, lost much of his influence. Guipago refused to go to Washington before having met with Satanta and Big Tree, and was allowed to meet them in St. Louis; in Washington he was firm and steady, until the Secretary of the Interior asked if they were freed, if the Kiowa would walk the "peace path." Guipago and Kicking Bird promised they would, and so Texas authorities released Satanta and Big Tree on parole from the Huntsville penitentiary in late 1873. General Sherman, along with most Texans, was enraged, and he wrote to the Governor, "I believe Satanta and Big Tree will have their revenge, if they have not already had it, and if they are to take scalps, I hope that yours is the first that will be taken." In spite of this general protest, the officials were following the advice of the Secretary of the Interior, who was so anxious to secure peace on the frontier that he accepted a pledge by the Kiowas and Comanches that upon the release of the two chiefs, they would yield and follow the path of peace.[2][8]

Hostilities continued nonetheless, and a year after their release Big Tree and Satanta were arrested for parole violation, participating in the attack on Adobe Walls and other acts occurring during the so-called Red River War. After an investigation Big Tree's parole was reinstated, but Satanta was returned to Huntsville for his involvement in the Second Battle of Adobe Walls. The Kiowa People deny he was involved in that battle, other than being present. He yielded up his war lance and other symbols of leadership to younger, more aggressive men, and did not take an active part in the battle. But his very presence there broke the terms of his parole, and back to prison he went. By 1878, Satanta could not go on any longer. The Kiowa chief who had been named the "orator of the Plains" at Medicine Lodge was reported by guards to be in a state of despair. In his book, the History of Texas, Clarance Wharton reports of Satanta in prison:

After he was returned to the penitentiary in 1874, he saw no hope of escape. For awhile he was worked on a chain gang which helped to build the M.K. & T. Railway. He became sullen and broken in spirit, and would be seen for hours gazing through his prison bars toward the north, the hunting grounds of his people.

The details of the story of his suicide are fairly well known, that he managed to crawl through a high window of the Huntsville facility and leap headfirst to his death on the bricks of the prison yard.[3]

While Satanta suffered in prison, Big Tree, returning to the reservation and accepting pacification, lived on in the sadness of a warrior in exile. He later became a Christian and eventually a minister in the Baptist church. There were days he would proudly recount his cruel acts against the white man, although it is faithfully recorded that he always concluded those tales with the solemn note that God had forgiven him for those "hideous" acts.[3]

Satanta is buried near Satank's remains (which were finally gathered from the road by the army, on Colonel MacKenzie's order) on Chief's Knoll, in the Fort Sill Cemetery, at Fort Sill, Oklahoma.[3]

Surviving his comrade Satanta by fifty years, Big Tree died in 1929. Fort Richardson, its purpose gone with the surrender of the Plains Tribes, was closed in 1876.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Wharton, Clarance. History of Texas

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Satanta (White Bear)". Archives and Manuscripts. Texas State Library & Archives Commission. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Boggs, Johnny. Spark on the Prairie

- ^ Peery, Dan W. "Chronicles of Oklahoma". March 1935. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on July 9, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ "Satanta (White Bear)" (PDF). "The New York Times", 27 June 1871. June 27, 1871. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ "Indian Relations in Texas". Texas State Library & Archives Commission. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ "Satanta (1830-1878)". Native American Ways. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- ^ "Kiowa Chief Satanta". Native American History. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

Literature

[edit]- Boggs, Johnny, Spark on the Prairie

- Haseloff, Cynthia, The Kiowa Verdict

- Mooney, James (1898). "Calendar History of the Kiowa Indians: Summer 1871". In J. W. Powell (ed.). Seventeenth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 328–333.

- Tatum, Lawrie (1899). Chapter VI, Our Red Brothers and the Peace Policy of President Ulysses S. Grant. Philadelphia: John C. Winston & Co. pp. 165–202. An account of the events as described by the first Indian Agent to the Kiowa. Also see United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Indian Affairs (1871). Item No. 80-1/2, Report from Lawrie Tatum, United States Indian Agent, Office Kiowa Agency, Indian Territory in Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs For The Year 1871. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 918–920., and United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Indian Affairs (1872). Papers, Item No. 23, Report from Lawrie Tatum, United States Indian Agent, Office Kiowa Agency, Indian Territory in Annual Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs For The Year 1872. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 247–248.

- Wharton, Clarance, History of Texas