University of Massachusetts Amherst

| |

Former names | Massachusetts Agricultural College (1863–1931)[1] Massachusetts State College (1931–1947) |

|---|---|

| Motto | Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem (Latin) |

Motto in English | "By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty." |

| Type | Public land-grant research university |

| Established | April 29, 1863[2] |

Parent institution | University of Massachusetts |

| Accreditation | NECHE |

Academic affiliations | Five Colleges |

| Endowment | $579 million (2024)[3] |

| Chancellor | Javier Reyes |

| Provost | Fouad Abd-El-Khalick[4] |

Academic staff | 1,550 (2023)[5] |

| Students | 31,810 (2023)[6] |

| Undergraduates | 23,936 (2023)[7] |

| Postgraduates | 7,874 (2023)[8] |

| Location | , , United States 42°23′20″N 72°31′40″W / 42.38889°N 72.52778°W |

| Campus | Large suburb, 1,463 acres (5.92 km2) |

| Newspaper | The Massachusetts Daily Collegian |

| Colors | Maroon and white[9] |

| Nickname | Minutemen and Minutewomen[10] |

Sporting affiliations |

|

| Mascot | Sam the Minuteman[11] |

| Website | www |

The University of Massachusetts Amherst (UMass Amherst) is a public land-grant research university in Amherst, Massachusetts, United States. It is the flagship campus of the University of Massachusetts system, and was founded in 1863 as the Massachusetts Agricultural College. It is also a member of the Five College Consortium, along with four other colleges in the Pioneer Valley.

UMass Amherst has the largest undergraduate population in Massachusetts with roughly 24,000 enrolled undergraduates.[12] The university offers academic degrees in 109 undergraduate, 77 master's, and 48 doctoral programs. Programs are coordinated in nine schools and colleges.[13] It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[14] According to the National Science Foundation, the university spent $211 million on research and development in 2018.[15][13]

The university's 21 varsity athletic teams compete in NCAA Division I and are collectively known as the Minutemen and Minutewomen. The university is a member of the Atlantic 10 Conference while playing ice hockey in Hockey East and football as an FBS independent school.

History

[edit]Foundation and early years

[edit]The university was founded in 1863 under the provisions of the Federal Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act to provide instruction to Massachusetts citizens in "agricultural, mechanical, and military arts." Accordingly, the university was initially named the Massachusetts Agricultural College. In 1867, the college had yet to admit any students and had not completed any buildings but had been through two presidents. That same year, William S. Clark was appointed president of the college and Professor of Botany. He appointed a faculty, coordinated the completion of construction, and, in the fall of 1867, welcomed the first class of approximately 50 students. Clark became the first president to serve long-term after the school's opening.[16] Of the school's founding figures, there are a traditional "founding four" – Clark, Levi Stockbridge, Charles Goessmann, and Henry Hill Goodell.[17][18]

The original buildings consisted of Old South College, North College, the Chemistry Laboratory, the Boarding House, the Botanic Museum, and the Durfee Plant House.[20]

The fledgling college grew under the leadership of President Henry Hill Goodell. In the 1880s, Goodell implemented an expansion plan, adding the College Drill Hall in 1883, the Old Chapel Library in 1885, and the East and West Experiment Stations in 1886 and 1890.

The early 20th century saw expansion in enrollment and curriculum. The first female student was admitted in 1875 on a part-time basis and the first full-time female student was admitted in 1892. In 1903, Draper Hall was constructed for the dual purpose of a dining hall and female housing. The first female students graduated with the class of 1905. The first dedicated female dormitory, the Abigail Adams House (on the site of today's Lederle Tower), was built in 1920.[21]

Modern era

[edit]By the 1970s, the University continued to grow and gave rise to a shuttle bus service on campus as well as many other architectural additions; this included the Murray D. Lincoln Campus Center complete with a hotel, office space, fine dining restaurant, campus store, and passageway to the parking garage, the W. E. B. Du Bois Library, and the Fine Arts Center.

Over the next two decades, the John W. Lederle Graduate Research Center and the Conte National Polymer Research Center were built and UMass Amherst emerged as a major research facility. The Robsham Memorial Center for Visitors welcomed thousands of guests to campus after its dedication in 1989. For athletic and other large events, the Mullins Center was opened in 1993.

21st century

[edit]In 2003, Massachusetts State Legislature designated the University of Massachusetts Amherst as a research university and the "flagship campus of the University of Massachusetts system".[22][23] The university was named a top producer of Fulbright Award winners in the 2008–2009 academic year. Additionally, in 2010, it was named one of the "Top Colleges and Universities Contributing to Teach For America's 2010 Teaching Corps."[24]

From World War II to 2023, the imagery on the official seal of the university was nearly identical to the state flag of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.[25] That image of the seal has been slowly removed starting in 2011, until March 2023 when a new image of the seal, featuring a profile of the Old Chapel spire, was ratified by the campus.[26]

Organization and administration

[edit]Colleges and schools

[edit]| College/School | Year founded |

| Stockbridge School of Agriculture | 1870 |

| College of Education | 1907 |

| College of Humanities & Fine Arts | 1915 |

| School of Public Health and Health Sciences | 1937 |

| College of Social and Behavioral Sciences | 1938 |

| Isenberg School of Management | 1947 |

| College of Engineering | 1947 |

| Elaine N. Marieb College of Nursing | 1953 |

| College of Natural Sciences | 2009 |

| Manning College of Information and Computer Sciences | 2015 |

| School of Public Policy | 2016 |

Since the University of Massachusetts Amherst was founded as the Massachusetts Agricultural College in 1863, 25 individuals have been at the helm of the institution.[27] Originally, the chief executive of UMass Amherst was a president. When UMass Boston was founded in 1963, it was initially reckoned as an off-site department of the Amherst campus and was headed by a chancellor who reported to the president. A 1970 reorganization transferred day-to-day responsibility for UMass Amherst to a chancellor as well, with both chancellors reporting on an equal basis to the president. The title "President of the University of Massachusetts" now refers to the chief executive of the entire five-campus University of Massachusetts system.

The current Chancellor of the Amherst campus is Javier Reyes.[28] The Chancellor resides in Hillside, the campus residence for chancellors.[29] Reyes is the first person of Hispanic descent to serve as Chancellor of the university.[28]

There are approximately 1,300 full-time faculty at the university.[13] The university is organized into nine schools and colleges and offers 111 bachelor's degrees, 75 master's degrees, and 47 doctoral degrees.[13]

Academics

[edit]Rankings and reputation

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[30] | 126 |

| U.S. News & World Report[31] | 58 |

| Washington Monthly[32] | 90 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[33] | 141 |

| Global | |

| ARWU[34] | 151–200 |

| QS[35] | 275 |

| THE[36] | 84 |

| U.S. News & World Report[37] | 175 |

U.S. News & World Report's 2025 edition of America's Best Colleges ranked UMass Amherst tied for 58th on their list of "Best National Universities", and tied for 26th among 225 public universities in the U.S.[38] UMass Amherst is accredited by the New England Commission of Higher Education.[39]

Commonwealth Honors College

[edit]Commonwealth Honors College at UMass provides students the opportunity to intensify their UMass academic curriculum. Membership in the honors college is not required to graduate from the University with designations such as magna or summa cum laude. In 2013, the University completed the Commonwealth Honors College Residential Community (CHCRC) on campus to serve the college, including classrooms, administration, and housing for 1,500 students and some faculty.[40]

Five College Consortium

[edit]UMass Amherst is part of the Five Colleges Consortium, which allows its students to attend classes, borrow books, work with professors, etc., at four other Pioneer Valley institutions: Amherst, Hampshire, Mount Holyoke, and Smith Colleges.

UMass Amherst holds the license for WFCR, the National Public Radio affiliate for Western Massachusetts. In 2014, the station moved its main operations to the Fuller Building on Main Street in Springfield, but retained some offices in Hampshire House on the UMass campus.[41]

Community service

[edit]The Community Engagement Program (CEP) offers courses that combine classroom learning and community service. Co-curricular service programs include the Alternative Spring Break, Engineers without Borders, the Legal Studies Civil Rights Clinical Project, the Medical Reserve Corps, Alpha Phi Omega, the Red Cross Club, the Rotaract Club, UCAN Volunteer, and the Veterans and Service Members Association (VSMA).

The White House has named UMass Amherst to the President's Higher Education Community Service Honor Roll for four consecutive years, in recognition of its commitment to volunteering, service learning, and civic engagement.[42] They have also been named a "Community-Engaged University" by the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.[43]

Research

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[44] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 61% | ||

| Asian | 11% | ||

| Hispanic | 8% | ||

| Foreign national | 7% | ||

| Other[a] | 7% | ||

| Black | 5% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[b] | 20% | ||

| Affluent[c] | 80% | ||

UMass research activities totaled more than $200 million in fiscal year 2014 ($257,407,928 in today's money).[13] In 2016, the faculty adopted an open-access policy to make its scholarship publicly accessible online.[45]

A team of scientists at UMass led by Vincent Rotello has developed a molecular nose that can detect and identify various proteins. The research appeared in the May 2007 issue of Nature Nanotechnology, and the team is currently focusing on sensors, which will detect malformed proteins made by cancer cells.[46] Also, UMass Amherst scientists Richard Farris, Todd Emrick, and Bryan Coughlin led a research team that developed a synthetic polymer that does not burn. This polymer is a building block of plastic, and the new flame-retardant plastic will not need to have flame-retarding chemicals added to its composition. These chemicals have recently been found in many different areas from homes and offices to fish, and there are environmental and health concerns regarding the additives. The newly developed polymers would not require the addition of potentially hazardous chemicals.[47]

Admissions and enrollment

[edit]In 2012, the university reported that applications to the school had more than doubled since the Fall of 2003 and increased more than 80% since 2005.[48][49]

The incoming Class of 2022 had an average high school GPA of 3.90 out of a 4.0 weighted scale, up from an average GPA of 3.83 the year before. The average SAT score of the Class of 2022 was 1294/1600, and on average the students ranked in the top fifth of their high school class. Acceptance to the Commonwealth Honors College program of UMass Amherst is more selective with an average SAT score of 1409/1600 and an average weighted high school GPA of 4.29.[50]

Campus

[edit]

The University's campus is situated on 1,450 acres of historically Pocumtuc land,[53] mainly in the town of Amherst, but also partly in the neighboring town of Hadley. The campus extends about 1 mile (1.6 km) from the Campus Center in all directions and may be thought of as a series of concentric rings, with the innermost ring harboring academic buildings and research labs, surrounded by a ring of the seven residential areas and two university-owned apartment complexes. These include North Apartments, Sylvan, Northeast, Central, Orchard Hill, Southwest, Commonwealth Honors College Residential Complex., The two university-owned apartment complexes, North Village and Lincoln Apartments were demolished. They were replaced by a private development called Fieldstone on the former Lincoln Apts. site for undergraduate and graduate students and university owned apartments for family housing called University Village on the former North Village site .[54][55] These are in turn surrounded by a ring of athletic facilities, smaller administration buildings, and parking lots.

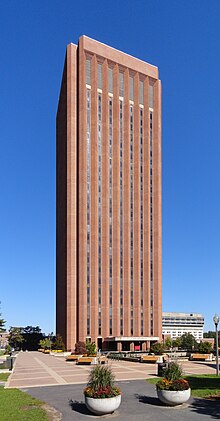

Libraries

[edit]The W.E.B. Du Bois Library is one of two library buildings on campus and the tallest academic research library in the world, standing 26 stories above ground and 286 feet (90.32 m) tall.[56] Before its construction in the late 1960s, Goodell Hall was the University library, which was built after the library had outgrown its space in the 1885 "Old Chapel" building. Originally known as Goodell Library, the building was named for Henry H. Goodell, who had served as College Librarian, Professor of Modern Languages and English Literature, and eighth President of the Massachusetts Agricultural College. The Library is well regarded for its innovative architectural design, which incorporates the bookshelves into the structural support of the building.[57] It is home of the memoirs and papers of the distinguished African-American activist and Massachusetts native W. E. B. Du Bois, as well as being the depository for other important collections, such as the papers of the late Congressman Silvio O. Conte. The library's special collections include works on movements for social change, African American history and culture, labor and industry, literature and the arts, agriculture, and the history of the surrounding region.[58]

The Science and Engineering Library is the other library building, located in the Lederle Graduate Research Center Lowrise.[citation needed]

UMass is also home to the DEFA Film Library, the only archive and study collection of East German films outside of Europe. It was founded in 1993 by Barton Byg, professor of film and German Studies, and so named after the Deutsche-Film Aktiengesellschaft, the East German film company founded in 1946. Some years after German reunification, in 1997, an agreement with two German partners led to the creation of a collection of East German film journals along with a large collection of 16mm and 35mm prints of DEFA films. More have been added since.[59]

The Shirley Graham Du Bois Library is located in the New Africa House.[citation needed]

Other buildings and facilities

[edit]The university has several buildings (constructed in the 1960s and 1970s) of importance in the modernist style, including the Murray D. Lincoln Campus Center and Hotel designed by Marcel Breuer, the Southwest Residential Area designed by Hugh Stubbins Jr. of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, The Fine Arts Center by Kevin Roche, the W.E.B. Du Bois Library by Edward Durell Stone, and Warren McGuirk Alumni Stadium by Gordon Bunshaft. Many of the older dorms and lecture halls are built in a Georgian Revival style such as French Hall, Fernald Hall, Stockbridge Hall, and Flint Laboratory.

The campus facilities underwent extensive renovations during the late 1990s. New and newly renovated facilities include student apartment complexes, the Hampshire Dining Commons, a library Learning Commons, a School of Management, an Integrated Science Building, a Nursing Building, a Studio Arts Building, the Combined Heat and Power (CHP) generation facility, a track facility, and a Recreation Center. Newly completed construction projects on campus include the new Campus Police Station, the George N. Parks Minuteman Marching Band Building, the Life Sciences Laboratories, and the Integrated Learning Center.[60]

Residential life

[edit]Residential Life at the University of Massachusetts Amherst is one of the largest on-campus housing systems in the United States. Over 14,000 students live in 52 residence halls, while families, staff, and graduate students live in 345 units in two apartment complexes (North Village and Lincoln). The fifty-two residence halls and four undergraduate apartment buildings are grouped into seven separate and very different residential areas: Central, Northeast, Orchard Hill, Southwest, Sylvan, North Apartments, and the Commonwealth Honors College Residential Community (CHCRC).

Located in the central corridor of campus, the Honors Community houses undergraduate members of Commonwealth Honors College.[61]

Major campus expansion

[edit]

The University of Massachusetts Amherst campus embarked on a 10-year, $1 billion ($1,613,107,822 in today's money) capital improvement program in 2004, setting the stage for re-visioning the campus's future.[62][63][64] This includes construction of $156 million New Science Laboratory Building, $30 million Champions Basketball Center, an $85 million academic building, and $30 million in renovations to the football stadium.[65]

In early 2016, the construction of a new electrical substation located near Tillson Farm was completed.[66] The purpose of the substation is to supply electricity to the university more efficiently and reliably, with estimated savings of $1 million per year ($1,269,551 in today's money).[66] The project was created in partnership with the utilities company Eversource, and cost approximately $26 million ($33,008,319 in today's money).[66]

In April 2017, the University of Massachusetts Amherst officially opened its new Design Building. Previously estimated at $50 million ($62,150,421 in today's money) the 87,000 square feet (8,100 m2) facility is the most advanced CLT building in the United States and the largest modern wood building in the northeastern United States.[67][68]

Mount Ida Campus of UMass Amherst

[edit]

On April 6, 2018, Mount Ida College announced that the University of Massachusetts would be absorbing its campus. Mount Ida students were given a guaranteed transfer to UMass Dartmouth, and the campus became part of UMass Amherst. The campus was named Mount Ida Campus of UMass Amherst and functions as a satellite campus for UMass Amherst. The campus primarily serves as a hub for Greater Boston-area career preparation and experiential learning opportunities for UMass Amherst students. The programs that are offered at the newly acquired campus will align the strengths of UMass Amherst with the growing demand for talent in areas that drive the Massachusetts economy, including health care, business, computer science, and other STEM specialties.[69]

Campus safety

[edit]Campus safety features include controlled dormitory access, emergency telephones, lighted sidewalks, and 24-hour campus police patrols on feet and by vehicle.[70]

Riots occurred after the Boston Red Sox lost the 1986 World Series and won in 2004 and 2007, after the Red Sox were eliminated in the 2003 and 2008 playoffs, after UMass' football team lost in the Division I-AA football championship game in 2006 and after the Patriots first Super Bowl victory over St. Louis in Super Bowl XXXVI. The majority of these riots have been non-violent on the side of the students, except for the 1986 riot in which an argument between hundreds of students intensified into racial altercations where a black student was attacked and beaten to unconsciousness by fifteen to twenty white students according to archives from The Republican. In the wake of these events, students have worked to have open dialogues with the administration and police department about campus safety, the right to gather, the police force, and better methods of crowd control.[71]

Iranian student admissions controversy

[edit]

UMass Amherst issued an announcement in early 2015 stating, "The University has determined that it will no longer admit Iranian national students to specific programs in the College of Engineering (i.e., Chemical Engineering, Electrical & Computer Engineering, Mechanical & Industrial Engineering) and in the College of Natural Sciences (i.e., Physics, Chemistry, Microbiology, and Polymer Science & Engineering) effective February 1, 2015."[72] The University claims that this announcement was posted because a graduate student entered Iran for a project and was later denied a visa. This event along with urging from legal advisers contributed to the belief that such incidents inhibited their ability to give Iranian students a "full program of education and research for Iranian students" and thus justified changing their admissions policies. The ensuing criticism on and off campus, as well as wide media publicity, changed the minds of school officials. As a result, UMass made a statement on February 18 committing to once again allowing Iranian students to apply to the aforementioned graduate programs.[73] On the same day, an official in the U.S. Department of State stated in an interview that: "U.S. laws and regulations do not prevent Iranian people from traveling to the United States or studying in engineering program of any U.S. academic institutions."[74] UMass Amherst replaced the ban with a policy aimed at designing specific curricula for admitted Iranian nationals based on their needs. While less controversial, this policy has still generated backlash, with one student saying, "This university that's supposed to be so open-minded forcing him to sign a document saying he won't go home and build a bomb or something is just really disappointing to see."[75]

Student life

[edit]Arts on campus

[edit]The UMass Amherst campus offers a variety of artistic venues, both performance and visual art. The most prominent is the Fine Arts Center (FAC) built in 1975. The FAC brings theater, music, and dance performances to campus throughout the year into its performance spaces (Concert Hall, Bezanson Recital Hall, and Bowker Auditorium). These include several performance series: Jazz in July Summer Music Program, The Asian Arts & Culture Program, Center Series, and Magic Triangle Series presenting music, dance, and theater performances, cultural arts events, films, talks, workshops, masterclasses, and special family events. University Museum of Contemporary Art in the FAC has a permanent contemporary art collection of about 2,600 works and hosts numerous visual arts exhibitions each year as well as workshops, masterclasses, and artist residencies.[76]

The 9,000-seat Mullins Center, the multi-purpose arena of UMass Amherst hosts a wide variety of performances including speakers, rock concerts, and Broadway shows. In addition, the Music, Dance, and Theater Departments, the Renaissance Center, and multiple student groups dedicated to the arts provide an eclectic menu of performances throughout the year.

The Interdepartmental Program for Film Studies has been organizing the Massachusetts Multicultural Film Festival on campus since 1991.[77]

Groups and activities

[edit]UMass Amherst has a history of protest and activism among the undergraduate and graduate population[78] and is home to over 200 registered student organizations (RSOs).

Student Government Association

[edit]The Student Government Association (SGA) is the undergraduate student governmental body and provides funding for the many registered student organizations (RSOs) and agencies, including the Student Legal Services Office (SLSO) and the Center for Student Business (CSB). The SGA also makes formal recommendations on matters of campus policy and advocates for undergraduate students to the Administration, non-student organizations, and local and state government. As of the 2023 school year, the SGA had a budget of over $7.5 million per year, which is collected from students in the form of the $266 per year Student Activities Fee.[79]

UMass permaculture

[edit]UMass permaculture is one of the first university permaculture initiatives in the nation and transforms marginalized landscapes on the campus into diverse, educational, low-maintenance, and edible gardens.[80] Rather than tilling the soil, a more sustainable landscaping method known as sheet mulching is employed. In November 2010, "about a quarter of a million pounds of organic matter was moved by hand", using all student and community volunteer labor and no fossil fuels on-site.[81] The process took about two weeks to complete. Now, the Franklin Permaculture Garden includes a diverse mixture of "vegetables, fruit trees, berry bushes, culinary herbs, and a lot of flowers that will attract beneficial insects."[81]

Minuteman Marching Band

[edit]UMass Amherst has the largest marching band in New England. The Minuteman Marching Band consists of over 390 members and regularly plays at football games. The band also performs in various other places and events like the Collegiate Marching Band Festival in Allentown, Pennsylvania, Bands of America in Indianapolis, Symphony Hall, Boston, The Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, Tournament of Roses Parade in Pasadena, California, and on occasion Montreal, Quebec, Canada.

Fraternities and sororities

[edit]Fraternities, sororities, and honor societies have been present on the campus almost since inception, with its first fraternity, the Latin letter-named Q.T.V. emerging in 1869, and the first sorority, Delta Phi Gamma (local) in 1916.[d] Approximately 1,500 students are active members each academic year.[82][83][84]

Several fraternities had houses on North Pleasant Street until 2007 when several lots owned by Alpha Tau Gamma were sold to the university for $2,500,000 ($3,673,568 in today's money).[85] Alpha Tau Gamma, a local fraternity associated with the Stockbridge School of Agriculture, then donated $500,001 to endow the salary for the director of the Stockbridge School.[85]

Criticism of sexual and alcohol abuse in Greek Life Organizations has appeared repeatedly in Bostonian and national news. The university has responded by creating a sorority and fraternity accreditation program and scorecard publishing community service, educational programming, grade reports, and conduct reports on their website.[86][87] Some students have called for changes in policy.[88]

Media

[edit]The Massachusetts Daily Collegian

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (October 2024) |

The Massachusetts Daily Collegian, the official newspaper of UMass Amherst, is published Monday through Thursday during the calendar semester. The Collegian is a non-profit student-run organization that receives no funding from the university or student fees. The Collegian operates entirely on advertising revenues. Founded in 1890, the paper began as Aggie Life, became the College Signal in 1901, the Weekly Collegian in 1914, and the Tri-Weekly Collegian in 1956. Published daily since 1967, the Collegian has been broadsheet since January 1994.

WMUA 91.1 FM

[edit]The student-operated radio station, WMUA, is a federally licensed, non-commercial broadcast facility serving the Connecticut River Valley of Western Massachusetts, Northern Connecticut, and Southern Vermont. Although the station is managed by full-time undergraduate students of the University of Massachusetts, station members can consist of various members of the university (undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and staff), as well as people of the surrounding communities. WMUA began as an AM station in 1949.[citation needed]

WSYL-FM

[edit]There were two student-run, extremely-low-power FM radio stations from the mid-1970s through the 1980s: one that used the self-assigned identifier "WSYL-FM" (With Songs You Like) which operated in the basement of Cashin, and WOCH (OrChard Hill, the dormitory area), which operated from Grayson.[89]

Athletics

[edit]

UMass is a member of Division I of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA). The university is a member of the Atlantic 10 Conference while playing ice hockey in the Hockey East Association. The football team joined the Mid-American Conference (MAC), to play at Football Bowl Subdivision (FBS; the sport's highest level) with games played at Gillette Stadium in 2012.[90] In March 2014, the MAC and UMass announced an agreement for the Minutemen football team to leave the conference after the 2015 season due to UMass declining an offer to become a full member of the conference. In the agreement between the MAC and the university, there was a contractual clause that had UMass playing in the MAC as a football-only member for two more seasons if UMass declined a full membership offer. UMass announced that it would look for a "more suitable conference" for the team.[91] UMass was unable to find a "suitable conference" for nearly a decade, remaining a full A-10 member and becoming an FBS independent, but during the early-2020s conference realignment entered into membership discussions with both the MAC and Conference USA.[92] On February 29, 2024, it was announced that UMass would join the MAC as a full member, including football, in July 2025.[93]

UMass originally was known as the Aggies,[94] later the Statesmen, then the Redmen. In a response to changing attitudes regarding the use of Native American–themed mascots, they changed their mascot in 1972 to the Minuteman, based on the historical "minuteman" relationship with Massachusetts; women's teams and athletes are known as Minutewomen.

The UMass Amherst Department of Athletics currently sponsors men's intercollegiate baseball, basketball, cross country, ice hockey, football, lacrosse, soccer, swimming, and indoor and outdoor track & field. They also sponsor women's intercollegiate basketball, softball, cross country, rowing, lacrosse, soccer, swimming, field hockey, indoor and outdoor track & field, and tennis. Club sports offered which are not also offered at the varsity level are men's wrestling, men's rowing, men's tennis, women's ice hockey, men's and women's rugby, men's and women's bicycle racing, and men's and women's fencing. Men's and women's downhill skiing have been re-certified as club sports following the April 2, 2009, announcement of their discontinuation as varsity sports.[95]

Notable alumni

[edit]As of 2014, there were 243,628 University of Massachusetts Amherst alumni worldwide.[96] Notable UMass Amherst alumni include Greg Landry, Jeff Corwin, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Taj Mahal, Bill Paxton, William Monahan, Kenneth Feinberg, Bill Cosby,[97] Natalie Cole,[98] Julius "Dr. J" Erving, Rick Pitino, Bill Pullman, Betty Shabazz, Briana Scurry, Jack Welch, John F. Smith Jr., Jean Worthley, Jeff Reardon, Mike Flanagan, Lawrence Mestel, and Richard Gere.

- Notable alumni

-

Julius Erving, Hall of Fame basketball player

-

LTG Jody Daniels (MSc 1993, PhD 1997, Hon DSc 2019), 34th Chief of Army Reserve

-

Zhou Qifeng, 13th president of Peking University

-

Bill Cosby, Stand-up comedian and actor

-

Jack Welch (BSc 1957, Hon DSc 1982), Former chairman and CEO of General Electric

-

Anshuman Jain (MBA 1985), Former co-CEO and co-chairman of Deutsche Bank

-

Russell Hulse (PhD 1975), Nobel Prize in Physics

-

Steven Sinofsky, Former president of Windows at Microsoft

-

Betty Shabazz, Civil rights advocate

-

Richard Gere, Film actor and producer

Notable faculty and staff

[edit]Notable faculty have included Sheila Bair, the former chairman of the US Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation; Chuck Close, celebrated photorealist; Samuel R. Delany, author and critic; Vincent Dethier, pioneer physiologist; Ted Hughes, British poet laureate; Max Roach, considered one of the most important jazz drummers in history; Lynn Margulis, famed biologist; Stephen Resnick and Richard D. Wolff, heterodox economists; James Tate, Pulitzer Prize–winning poet; and Robert Paul Wolff, in both philosophy and African-American studies. Current faculty of note include poet Peter Gizzi, T. S. Eliot Prize–winning poet Ocean Vuong, media critic Sut Jhally, and feminist economist Nancy Folbre.

See also

[edit]- University of Massachusetts Amherst Department of Food Science

- William P. Brooks (1851–1938), professor, eighth president of the Massachusetts Agricultural College, and second vice president of Sapporo Agricultural College, Japan

- Campus of the University of Massachusetts Amherst

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

- ^ This local sorority was eventually split into four descendent chapters, with one of these in 1941 becoming the first nationally-affiliated chapter, joining Chi Omega.

References

[edit]- ^ "UMass Amherst: History of UMass Amherst". Archived from the original on May 16, 2006.

- ^ "UMass Amherst Looks to the Past and the Future at Founders Day". University of Massachusetts Amherst. April 29, 2008. Archived from the original on January 10, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2020.

- ^ "Endowment Overview". Archived from the original on May 24, 2021. Retrieved February 27, 2022.

- ^ "UMass Amherst: The Office of the Provost – Meet the Provost". www.umass.edu.

- ^ "University of Massachusetts Amherst: At a Glance 2021–2022" (PDF). University of Massachusetts Amherst. December 1, 2021. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2021. Retrieved September 22, 2022.

- ^ "2023–2024 Common Data Set" (PDF). University of Massachusetts Amherst. University of Massachusetts. 2024. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ "2023–2024 Common Data Set" (PDF). University of Massachusetts Amherst. University of Massachusetts. 2024. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ "2023–2024 Common Data Set" (PDF). University of Massachusetts Amherst. University of Massachusetts. 2024. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ "University of Massachusetts Amherst Athletics Official Style Guide" (PDF). Retrieved July 4, 2021.

- ^ "University of Massachusetts Official Athletic Site – Traditions". umassathletics.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "Mascots Talk Back: Sam the Minuteman". PATRICK SISSON/patricksisson.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ McFadden, Sean (March 9, 2023). "Largest Colleges & Universities in Massachusetts". Boston Business Journal. Retrieved July 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "UMass at a Glance". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on April 19, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ^ "Carnegie Foundation Classifications". carnegiefoundation.org. Archived from the original on September 13, 2018. Retrieved September 13, 2018.

- ^ "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. Archived from the original on September 30, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Frank Prentice Rand, Yesterdays at Massachusetts State College, (Amherst: The Associate Alumni of Massachusetts State College, 1933), pp. 17–19.

- ^ Hill, Joseph L. (November 7, 1935). Goodell – I Knew Him, [Dedication of the Goodell Library] (Speech). Amherst, Mass.

- ^ Neal, Robert Wilson (March 1911). "The College that the Bay State Built". Western New England. Vol. 1, no. 4. pp. 85–86.

To nearly all graduates up to 1900, or possibly 1905, the names of four such men especially (omitting even reference to trustees) were living names: Clark, Stockbridge, Goessmann, and Goodell. These were the most prominent of the faculty leaders who, by making the old M.A.C. from year to year, made possible the new M.A.C. Each had his characteristic part ... Clark, the dashing soldier, in the spectacular campaigns that accompanied the founding of the college; Stockbridge, of shrewd mother-wit and stubborn will, an embattled farmer is the cause of more popular education in carrying forward the institution at a time when it seemed to have lost all vitality and to live only from day to day as its saviors breathed upon it; Goessmann, scientist and German, in forming within the college the standards of exact scientific investigation. Last of the "Big Four" was President Henry H. Goodell—classicist, modern thinker, lover of literature and the arts, disciplinarian, sympathizer, self-forgetter.

- ^ "Past Presidents". Office of the President, University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on July 21, 2021. Retrieved July 21, 2021.

- ^ Rand, p. 21.

- ^ Rand, p. 147

- ^ "150 Years of UMass Amherst History". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ "Amherst is now legally the flagship of UMass system". The Massachusetts Daily Collegian. Retrieved September 18, 2003.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 11, 2010. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "UMass soliciting ideas to change flagship's seal". gazettenet.com. October 31, 2022. Archived from the original on February 5, 2023. Retrieved February 5, 2023.

- ^ "New University Seal and Brand Mark Unveiled by UMass Amherst, Providing Distinctive Additions to University's Visual Identity System : UMass Amherst". Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ University of Massachusetts, Office of the Chancellor, Former Chancellors and Presidents of the Amherst Campus [1] Archived May 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Dr. Javier Reyes appointed Chancellor of UMass Amherst". University of Massachusetts Amherst. February 16, 2023.

- ^ "Hillside House [YouMass ]". Archived from the original on October 9, 2012. Retrieved July 9, 2012. Hillside House Last Updated: 2012. Accessed: July 9, 2012.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 23, 2024. Retrieved November 22, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "2024 Academic Ranking of World Universities". ShanghaiRanking Consultancy. August 15, 2024. Retrieved August 21, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. June 24, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "U.S. News Best Colleges Rankings: University of Massachusetts—Amherst". U.S. News & World Report. Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ Massachusetts Institutions – NECHE, New England Commission of Higher Education, archived from the original on October 9, 2021, retrieved May 26, 2021

- ^ "Commonwealth Honors College Residential Complex". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on February 2, 2013. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ^ Public radio station WFCR-FM plans move from Amherst to Springfield Archived October 18, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. masslive.com. Retrieved on October 31, 2013.

- ^ "Corporation for National and Community Service". learnandserve.gov. Archived from the original on February 14, 2008.

- ^ "Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching". Archived from the original on September 16, 2014.

- ^ "College Scorecard: University of Massachusetts Amherst". United States Department of Education. Archived from the original on June 25, 2022. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ Jerome, Erin (November 29, 2016). "University of Massachusetts Amherst". ROARMAP: Registry of Open Access Repository Mandates and Policies. UK: University of Southampton. Archived from the original on July 14, 2017. Retrieved July 24, 2018.

- ^ UMass Amherst Scientists Create Nano Nose With Aim of Sniffing Out Diseased Cells, UMass Amherst, April 23, 2007. Archived May 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ UMass Amherst Scientists Create Fire-Safe Plastic, UMass Amherst, May 30, 2007. Archived November 4, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "UMass Amherst Welcomes Highest-Achieving First-Year Class When School Opens Labor Day Weekend". UMass. August 28, 2012. Archived from the original on September 1, 2012. Retrieved August 29, 2012.

- ^ "For Fifth Straight Year, UMass Amherst Welcomes Highest-Achieving First-Year Class as Students Return to Flagship Campus". UMass. August 31, 2015. Archived from the original on September 1, 2015.

- ^ "UMass Amherst Welcomes its Most Academically Accomplished and Diverse First-Year Class". Archived from the original on September 12, 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ Oswald, Godfrey (2008). Library World Records, Second edition. McFarland. p. 656. ISBN 978-0-7864-3852-5.

- ^ "Ten Tallest Library Buildings" Archived January 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Scribd.com

- ^ "UMass Land Acknowledgement". UMass Amherst.

- ^ Appelstein, Leigh (April 20, 2021). "University takes next steps toward building new student housing". Massachusetts Daily Collegian. Archived from the original on July 4, 2023.

- ^ https://www.umass.edu/news/article/university-village-welcoming-first-residents

- ^ "W.E.B. Du Bois Library". Emporis. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ Letzler, B (November 30, 2006). "Colleges' moves to shake up libraries speak volumes". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on October 23, 2012. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ "Special collections and university archives (SCUA)". UMass Amherst. Archived from the original on December 17, 2009. Retrieved December 11, 2009.

- ^ "About us". DEFA Film Library, UMass Amherst. Retrieved November 8, 2024.

- ^ "UMass Amherst Lists Building and Renovations Projects". Office of News & Media Relations | UMass Amherst. Archived from the original on January 13, 2019. Retrieved June 6, 2018.

- ^ "Roots Café – UMass Dining". www.umassdining.com. Archived from the original on July 11, 2015.

- ^ "UMass Amherst Adopts Physical Master Plan, Creating Foundation for Development over the Next Half Century". University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original on February 1, 2013. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ "UMass Amherst: Master Plan final document" (PDF). University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2013. Retrieved January 19, 2013.

- ^ "Five-year construction plan totals $1.1 billion at UMass". Gazettenet.com. Archived from the original on April 15, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ "Building up: UMass-Amherst campus expands". University of Massachusetts Amherst. January 5, 2012. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2013.

- ^ a b c "New Electrical Substation Increases Reliable Supply of Electricity for Campus". Office of News & Media Relations | UMass Amherst. Archived from the original on August 13, 2019. Retrieved August 13, 2019.

- ^ "Photos: UMass Amherst opens new Design Building, largest modern wood structure in the Northeastern US". masslive.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved April 25, 2017.

- ^ "UMass Amherst has new projects in design phase, including physical sciences building". masslive.com. December 14, 2013. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 28, 2014.

- ^ "Mount Ida College Reaches Agreement with UMass Regarding Educational Continuity for Students with Acquisition of its Campus". April 6, 2018. Archived from the original on April 6, 2018. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- ^ "University of Massachusetts—Amherst Campus, Campus Life". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved September 24, 2024.

- ^ "Riot police disperse 1,500 students at UMass-Amherst following Super Bowl". masslive.com. February 6, 2012. Archived from the original on October 15, 2014.

- ^ UMass Amherst Procedures on Admission of Iranian Students Archived February 14, 2015, at the Wayback Machine. umass.edu. Retrieved on February 13, 2015

- ^ "UMass Amherst Will Accept Iranian Students into Science and Engineering Programs, Revising Approach to Admissions". February 18, 2015. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ U.S. foreign minister: There is no program or law that prevents Iranian from studying in U.S. Archived February 16, 2015, at the Wayback Machine bbc.co.uk. Retrieved February 14, 2015

- ^ Annear, Steve; Bosco, Eric (February 18, 2015). "UMass reverses policy on Iranian students". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on May 25, 2015. Retrieved May 25, 2015.

- ^ University of Massachusetts Fine Arts Center: UMCA page, 'About' Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Last Updated: 2011. Accessed: May 14, 2011.

- ^ Massachusetts Multicultural Film Festival Archived February 26, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Last Updated: 2013. Accessed: March 2, 2013.

- ^ Flint, Anthony (November 18, 1989). "UMASS STUDENT STRIKE FUELS SPIRIT OF ACTIVISM". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 29, 2011. Retrieved February 17, 2011.

- ^ Genovese, Alex (February 17, 2022). "UMass SGA votes to increase student fees". The Massachusetts Daily Collegian. Archived from the original on February 17, 2022. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ Permaculture garden at UMass gives new meaning to the phrase fresh vegetables Archived February 2, 2016, at the Wayback Machine The Daily Hampshire Gazette

- ^ a b UMass Embraces Permaculture[dead link] Food Service Director

- ^ "Sorority and Fraternity Life: History and Purpose". UMass Amherst. University of Massachusetts Amherst. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ William Raimond Baird; Carroll Lurding (eds.). "Almanac of Fraternities and Sororities (Baird's Manual Online Archive)". Student Life and Culture Archives. University of Illinois: University of Illinois Archives. The main archive URL is The Baird's Manual Online Archive homepage.

- ^ Anson, Jack L.; Marchenasi, Robert F., eds. (1991) [1879]. Baird's Manual of American Fraternities (20th ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Baird's Manual Foundation, Inc. p. II-108. ISBN 978-0-9637159-0-6.

- ^ a b Holly Angelo (October 6, 2006). "Facilities and Campus Planning UMass Buys 5 Houses". The Republican. Archived from the original on November 12, 2007. Retrieved April 24, 2007.

- ^ "UMass-Amherst Fraternity Indicted On Hazing, Alcohol Charges". CBS News. September 21, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2023.

- ^ Krantz, Laura; Carlin, Julia (November 27, 2021). "'It's baffling that they exist': Some students call on UMass to rein in fraternities, sharing disturbing experiences". Boston Globe.

- ^ McGrath, Cassie (February 21, 2023). "Five months after protests over sexual assault and Greek life erupted at UMass Amherst, what has changed?". Mass Live.

- ^ "Tiny Little Stations". UMass Magazine. Spring–Summer 2000. Archived from the original on October 24, 2022. Retrieved October 1, 2024.

- ^ Connolly, John (April 20, 2011). "UMass moves up to FBS". Boston Herald. Archived from the original on April 25, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ UMass Football Will Leave Mid-American Conference at End of 2015 – University of Massachusetts Official Athletic Site Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. Umassathletics.com (March 26, 2014). Retrieved on April 12, 2014.

- ^ Thamel, Pete (February 26, 2024). "Sources: UMass set to become 13th member of MAC for '25-26 season". ESPN.com. Retrieved February 26, 2024.

- ^ "Mid-American Conference to Add University of Massacusetts as Full Member" (Press release). Mid-American Conference. February 29, 2024. Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ "Hockey and Baseball Schedules are Announced". Bowdoin Orient. December 2, 1925. Retrieved May 24, 2023.

- ^ "UMass baseball program spared, but men's and women's skiing dropped from athletic budget". masslive.com. April 2, 2009. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016.

- ^ "FactBook 2013–2014: Alumni" (PDF). University of Massachusetts Amherst. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 12, 2014. Retrieved May 12, 2014.

- ^ Strauss, Valerie (November 24, 2014). "Bill Cosby's doctoral thesis was about using 'Fat Albert' as a teaching tool". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 4, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ^ Langer, Emily. "Natalie Cole, singer and daughter of Nat King Cole, dies at 65". Washington Post. Archived from the original on January 11, 2016. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

Further reading

[edit]- Einhorn Yaffee Prescott; Vanasse Hangen Brustlin, Inc.; Pressley Associates (August 2009). University of Massachusetts Amherst Historic Building Inventory: Final Survey Report (PDF) (Report). University of Massachusetts Special Collections & University Archives (SCUA). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 3, 2014. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- Greider, Katharine (2013). UMass Rising: The University of Massachusetts Amherst at 150. Amherst, Mass.: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-1-55849-989-8. OCLC 795756630.

- Sullivan, Steven R. (2004). University of Massachusetts Amherst. The Campus History Series. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 978-0-7385-3530-2. OCLC 57679532.

- Sullivan, Steven R. (2006). University of Massachusetts Amherst Athletics. Images of Sports. Charleston, SC: Arcadia. ISBN 9780738544687. OCLC 69173788.

External links

[edit]- University of Massachusetts Amherst

- 1863 establishments in Massachusetts

- Business schools in Massachusetts

- Flagship universities in the United States

- Land-grant universities and colleges

- Public universities and colleges in Massachusetts

- Universities and colleges established in 1863

- Universities and colleges in Amherst, Massachusetts

- University of Massachusetts Amherst schools

- University of Massachusetts campuses