Ulric Dahlgren

Ulric Dahlgren | |

|---|---|

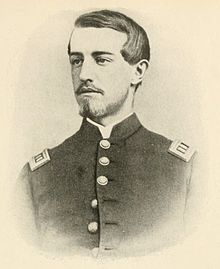

Col. Ulric Dahlgren (seen here as a captain) | |

| Born | April 3, 1842 Bucks County, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Died | March 2, 1864 (aged 21) near Stevensville, Virginia |

| Buried | Laurel Hill Cemetery, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S. |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1861–1862 (Union Navy) 1862–1864 (Union Army) |

| Rank | |

| Battles / wars | |

| Relations | John A. Dahlgren (father) Charles G. Dahlgren (uncle) |

Ulric Dahlgren (April 3, 1842 – March 2, 1864) was an American military officer who served as colonel in the Union Army during the American Civil War. He was the son of Union Navy Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren and nephew to Confederate Brigadier General Charles G. Dahlgren.

He fought in several key battles in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War and had his leg amputated below the knee after being wounded at the Battle of Gettysburg. He returned to military service and was killed in 1864 during the Battle of Walkerton while leading a raid on the Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia.

Confederate forces found documents on Dahlgren with orders to not only free Union prisoners from Belle Isle, but also allegedly to burn the city of Richmond and assassinate Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. The documents were published in the Richmond newspapers and caused outrage in the South with accusations that the orders came from President Lincoln. Union newspapers claimed the papers were forged and reports of mistreatment of Dahlgren's corpse inflamed public opinion in the North. The controversy became known as the Dahlgren Affair.

Early life

[edit]

Dahlgren was born on April 3, 1842, in Bucks County, Pennsylvania. He was the second son to Rear Admiral John A. Dahlgren and Mary Clement Bunker.[1] His uncle, Charles G. Dahlgren, settled in Mississippi and joined the Confederate Army as a general.

The family moved to Wilmington, Delaware, in 1843 and then to Washington, D.C. in 1848.[2] After completing school in 1858, Dahlgren's father instructed him in civil engineering and in 1859, he worked surveying land for his uncle, Charles G. Dahlgren, in Mississippi.[3] In September 1860, he moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, and worked in the law office of another uncle, Jasper W. Paul.[4]

American Civil War

[edit]Dahlgren entered military service in March 1861, and on July 24, 1861, joined the U.S. Navy. He was assigned to an expedition from the Washington Ship Yard to help in the defense of Alexandria, Virginia.[5] He returned to Philadelphia in September 1861 and resumed his legal studies. He was part of a light artillery company in Philadelphia.[6]

In May 1862, he was sent to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, and placed in charge of a battery of Navy howitzers.[7] On May 29, 1862, Dahlgren was sent back to Washington to obtain ammunition supplies. He visited his father who was meeting with President Abraham Lincoln and the U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton at the time. Lincoln asked Ulric for an overview of his experience in the military.[8] After Ulric's summary of his experience, Stanton offered him a position in the U.S. Army as captain and aide-de-camp to General Franz Sigel.[6]

He fought at the Second Battle of Bull Run, the Battle of Fredericksburg, the Battle of Chancellorsville, the Battle of Brandy Station, and the Battle of Gettysburg. During the Battle of Fredericksburg, he and sixty Union cavalry captured the city and held it for three hours. They were eventually forced to retreat, but were able to take thirty-one confederate prisoners.[6] On March 1, 1863, he joined the staff of General Joseph Hooker[9] and was retained on the staff of General George Meade when he took over the Army of the Potomac.[6] He was wounded in the foot on July 6, 1863, during the Battle of Gettysburg in a skirmish in Hagerstown, Maryland[10] and had his leg amputated below the knee.[11] For these efforts, Dahlgren received a Commission as colonel on July 24, 1863.[6]

Kilpatrick-Dahlgren raid

[edit]

After recovering from his injury, Dahlgren met Brig. Gen. Hugh Judson Kilpatrick on February 23, 1864, at a party and was invited to participate in an operation to attack Richmond, Virginia; rescue Union prisoners from Belle Isle and damage Confederate infrastructure.[12] The operation is also known as the Battle of Walkerton.[13]

On February 28, Kilpatrick and Dahlgren left from Stevensburg, Virginia. Kilpatrick was to attack Richmond from the North with 3,500 men and Dahlgren from the South with 500 men. Snow, sleet and rain from an unexpected winter storm slowed the attack.[14] Dahlgren's forces were led to a ford on the James River near Dover Mills by an African-American guide, Martin Robinson. The troops were not able to cross due to high water from recent rains. Dahlgren believed he had been tricked by the guide and had him hanged as punishment.[12]

Dahlgren redirected his troops to attack Richmond from the East. They heard the sound of battle and rushed to support Kilpatrick but ran directly into a Confederate Home Guard force which halted their advance.[14] Dahlgren retreated East in an attempt to connect with Kilpatrick's force.[12] The Union troops were continually harassed by Confederate forces during the retreat and became separated. On the night of March 3, Dahlgren and a portion of his troops were ambushed near King and Queen Court House by 150 men in the 9th Virginia Cavalry under the command of Lieutenant James Pollard. Dahlgren was shot by four bullets and died on the battlefield. Several other Union soldiers were killed in the ambush[14] and 135 were captured.[15]

Dahlgren affair

[edit]

Dahlgren's body was searched by a 13-year-old boy, William Littlepage. He was searching for valuables but found a packet of papers that he gave to his teacher Edward Halbach.[16] The papers were orders to free Union prisoners from Belle Isle, supply them with flammable material and torch the city of Richmond. The orders of Union troops purportedly were to capture and kill Confederate President Jefferson Davis and his cabinet. The papers were published in the Richmond Examiner and sparked outrage in the South.[17] The newspapers compared Dahlgren to Attila the Hun and speculated that Lincoln himself had given the orders.[14]

Dahlgren was originally interred where he was shot and killed.[18] An outraged mob disinterred his body and placed it on display at the York River Railroad depot in Richmond.[19] Dahlgren's wooden leg was displayed in a store window and his finger was cut off to remove a ring.[18] These reports of the mistreatment of Dahlgren's corpse inflamed Northern public opinion.[20]

Union newspapers claimed the orders were a forgery and Dahlgren's father strongly denied his son would be involved in such a scandal. Union Major General George Meade had to personally assure Confederate General Robert E. Lee that the orders were not sanctioned by the Union Army.[21] The controversy may have contributed to John Wilkes Booth's decision to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln a year later.[22]

It was never determined if the orders were written by Dahlgren, Kilpatrick, Edwin M. Stanton or President Lincoln. The papers misspelled Dahlgren's name which casts doubt that they were written by him. After the war, the papers of the Confederate Government were relocated to Washington, D.C. The Dahlgren papers were personally requested by Stanton and have not been seen since.[14]

Burial

[edit]

After the public display of his corpse, Dahlgren was interred in an unmarked grave at Oakwood Cemetery in Richmond.[18] His father petitioned to have Ulric's body returned for burial in Philadelphia. He made four trips to Fort Monroe to try to arrange an agreement and even contacted the Confederate Commissioner of Exchange to formally request the return of Ulric's remains.[23] The Union spy Elizabeth Van Lew used her connections in Richmond to secretly exhume his remains and reinter them at a farm 10 miles outside of Richmond[24] to prevent further desecration of his body.[18] Dahlgren was eventually interred at Laurel Hill Cemetery in Philadelphia.[25]

Citations

[edit]- ^ Dahlgren 1872, p. 11.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, pp. 11–13.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, p. 20.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, p. 27.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c d e Powell, William Henry (1893). Officers of the Army and Navy (volunteer) who Served in the Civil War, Volume 1. Philadelphia: L.R. Hamersly & Co. p. 64. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, p. 59.

- ^ Schultz 1998, p. 95.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, pp. 168–170.

- ^ Brock, R.A. (1909). Southern Historical Society Papers, Volumes 37-38. Richmond, Virginia: Southern Historical Society. p. 352. Retrieved 4 March 2021.

- ^ a b c "Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Wertz, Jay and Bearss, Edwin C. (1999). Smithsonian's Great Battles & Battlefields of the Civil War. HarperCollins Publisher. p. 693. ISBN 9780688170240. Retrieved 9 March 2021.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e McNeer, John. "Dahlgren's 1864 Raid on Richmond Generates an Ongoing Controversy". www.historyarch.com. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Ashe, Samuel A'Court (1925). History of North Carolina. Raleigh: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company. p. 877. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ "The Dahlgren Affair". www.historynaked.com. 4 August 2017. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Rhodes 1920, p. 514.

- ^ a b c d Suhr, Robert. "The Dahlgren Affair: Kilpatrick-Dahlgren Raid on Richmond". www.warfarehistorynetwork.com. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, p. 227.

- ^ "Van Lew, Elizabeth L. (1818-1900)". www.encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved 3 March 2021.

- ^ Rhodes 1920, p. 515.

- ^ Wittenberg, Eric J. "Ulric Dahlgren in the Gettysburg Campaign". Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ^ Schultz 1998, p. 190.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Dahlgren 1872, p. 287.

Sources

[edit]- Dahlgren, John Adolphus Bernard and Madeleine Vinton (1872). Memoir of Ulric Dahlgren. By His Father, Rear-Admiral Dahlgren. J.B. Lippincott & Co.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1920). History of the United States from The Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896. The MacMillan Company.

- Schultz, Duane (1998). The Dahlgren Affair: Terror and Conspiracy in the Civil War. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-04662-1.

- 1842 births

- 1864 deaths

- American amputees

- American failed assassins

- American people of Swedish descent

- Burials at Laurel Hill Cemetery (Philadelphia)

- Cavalry commanders

- Deaths by firearm in Virginia

- Military personnel from Bucks County, Pennsylvania

- People of Pennsylvania in the American Civil War

- Union army colonels

- Union military personnel killed in the American Civil War

- Union Navy sailors