User:AlasdairDaw/sandbox

Background

[edit]BUF announce march

[edit]The British Union of Fascists (BUF) had advertised a march to take place on Sunday 4 October 1936, the fourth anniversary of their organisation. Thousands of BUF followers, dressed in their Blackshirt uniform, intended to march through the heart of the East End, an area which then had a large Jewish population.[1]

The BUF would march from Tower Hill and divide into four columns, each heading for one of four open air public meetings where Mosley and other speakers would address gatherings of BUF supporters. The meetings were to be at Limehouse, Bow, Bethnal Green and Hoxton.[2]

Calls for a ban

[edit]The Jewish People's Council (and others, or among others)(Explain who they were) organised a petition, calling for the march to be banned, which gathered the signature of 100,000 East Londoners, including the Mayors of the five East London Boroughs (Hackney, Shoreditch, Stepney, Bethnal Green and Poplar)[3][4] in two days.[5] Home Secretary

The petition was presented to the Home office by representatives of a broad coalition of local groups:

Labour MP for Whitechapel and St Georges

Trade Unionist, Secretary of the London Trades Council

Anglican Priest at Christ Church on Watney Street, President of the Stepney Tenants Defence League and senior member of the Independent Labour Party

- Representatives of the Jewish Peoples Council

John Simon denied the request to outlaw the march.[6]

Counter-protest organised

[edit]Jewish chronicle says no (nat archives) Labour party said no (ref)

ILP - when Communists initially said no - changed

Background

[edit]The British Union of Fascists (BUF) had advertised a march to take place on Sunday 4 October 1936, the fourth anniversary of their organisation. Thousands of BUF followers, dressed in their Blackshirt uniform, intended to march through the heart of the East End, an area which then had a large Jewish population.[7]

The BUF would march from Tower Hill and divide into four columns, each heading for one of four open air public meetings where Mosley and other speakers would address gatherings of BUF supporters. The meetings were to be at Limehouse, Bow, Bethnal Green and Hoxton.[2]

The Jewish People's Council organised a petition, calling for the march to be banned, which gathered the signature of 100,000 East Londoners, including the Mayors of the five East London Boroughs (Hackney, Shoreditch, Stepney, Bethnal Green and Poplar)[8][9] in two days.[5] Home Secretary John Simon denied the request to outlaw the march.[10]

Tower Hill

[edit]The fascists were to gather from all over southern England, at and around Tower Hill for 2:30 p.m; the first to arrive did so in a piecemeal fashion from around 1:25 p.m; and were vulnerable to groups of hostile local people, around 500 in total, waiting for them. A party entering Tower Hill from nearby Mark Lane tube station was attacked, as was a group in Mansell Street.The anti-fascists also temporarily occupied the Minories.[11][12]

The fighting intensified as more as more anti-fascists and BUF members arrived, many BUF arriving in vans and cars whose windows had been reinforced with iron grilles. A private car bearing the slogan "Mosley shall not pass" drove onto Royal Mint Street, veering through the melee. A crowd of Fascists attacked it and Police cleared them away with a baton charge, the car making it's escape.

At 2pm the Police began the process of separating the factions, by the time which time there were already a significant number of injuries including Tommy Moran, who was leading the BUF force until Mosley's later arrival.[11]

There was fierce fighting as Police then moved on the counter-protesters to clear the crossroads where Royal Mint Street, Leman Street, Dock Street and Cable Street meet. The counter-protesters were moved onto these neighbouring streets, including a large number forced into Dock Street.[12]

Background

[edit]The British Union of Fascists (BUF) had advertised a march to take place on Sunday 4 October 1936, the fourth anniversary of their organisation. Thousands of BUF followers, dressed in their Blackshirt uniform, intended to march through the heart of the East End, an area which then had a large Jewish population.[14]

The BUF would march from Tower Hill and divide into four columns, each heading for one of four open air public meetings where Mosley and other speakers would address gatherings of BUF supporters. The meetings were to be at Limehouse, Bow, Bethnal Green and Hoxton.[15]

The Jewish People's Council organised a petition, calling for the march to be banned, which gathered the signature of 100,000 East Londoners, including the Mayors of the five East London Boroughs (Hackney, Shoreditch, Stepney, Bethnal Green and Poplar)[16][17] in two days.[5] Home Secretary John Simon denied the request to outlaw the march.[18]

Field of operations

[edit]A legacy of the City of London's long since demolished defensive wall, is that there are only three main routes into the East End from the direction of the City of London. From north to south these are; Bishopsgate, Aldgate (440 metres south-east of Bishopsgate) and Tower Hill (450 metres south of Aldgate).

The BUF was to gather its supporters at the southernmost of these three entrances; at Tower Hill and adjacent Royal Mint Street in East Smithfield, at 2:30. The intention was that Mosley would formally review the assembled force, after which time it would march from Tower Hill and divide into four columns, each heading for one of four open air public meetings where Mosley and other speakers, including William Joyce, John Beckett, Tommy Moran and Alexander Raven Thomson, would address gatherings of BUF supporters:[19][11][20]

- Salmon Lane, Limehouse at 5pm

- Stafford Road, Bow at 6pm

- Victoria Park Square, Bethnal Green at 6pm

- Aske Street, Hoxton at 6:30pm

In response, their opponents, who knew of the intended meetings but not the intended routes from Tower Hill, called on the main mass of their support to gather at the central of East End's three entry points, Aldgate for 2pm. In doing this the crowd could occupy the important road junctions in that area, most importantly Gardiner's Corner.

The aim of the Police was to allow the march to proceed as peacefully as possible. The head of the Metropolitan Police, Sir Philip Game, established his HQ at the junction of Mansell and Royal Mint Streets by Tower Hill. The Police also had a major Police Station halfway along Leman Street, between Tower Hill and Aldgate.[12]

Numbers involved

[edit]Very large numbers of people took part in the events, in part due to the good weather, but estimates of the numbers of participants vary enormously:

- Estimates of Fascist participants range from 2,000 to 3,000, up to 5,000.[11][21] The Fascists had a casualty dressing station at their Tower Hill assembly point.[11]

- There were 6,000–7,000 policemen, including the whole of the Metropolitan Police Mounted Division.[11][21][12] The Police had wireless vans and a spotter plane[11] sending updates on crowd numbers and movements to Sir Philip Game's HQ, at Tower Hill.[12]

- Estimates of the number of anti-fascist counter-demonstrators range from 100,000[11][22] to 250,000,[23] 300,000,[24] 310,000[25] or more.[26] The Independent Labour Party and Communists, like the Fascists, set up medical stations to treat their injured.[11]

so arranged local leadership along four of the most likely avenues of Fascist advance (Ref):

- Aldgate

- Leman Street

- Cable Street

- St Georges Highway (now called The Highway)

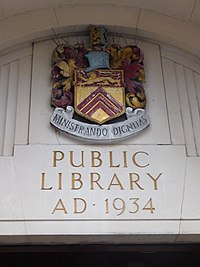

==Leyton Coat of Arms http://www.civicheraldry.co.uk/essex_ob.html#leyton_bc http://www.civicheraldry.co.uk/great_london.html#waltham%20forest%20lb https://www.heraldry-wiki.com/wiki/Leyton The coat of arms of the municipal borough were granted on 27 November 1926. The arms were described as "Or three Chevronels Gules on a Chief Gules a Lion passant Or".

The crest was: "On a Wreath Or and Gules a Lion rampant per pale Or and Sable supporting a Crozier Gold".

The Latin language motto was "MINISTRANDO DIGNITAS" meaning "dignity in service".

Elements of the arms commemorated various families who had held manors within the borough during the Middle Ages, and also the nearby Stratford Langthorne Abbey which had held lands in Leyton before the Dissolution of the Monasteries.[10] T

Which!

he lion and cross-staff on the crest of the Leyton arms have been preserved in the arms of the London Borough of Waltham Forest, which were granted on 1 January 1965.[11]

http://www.civicheraldry.co.uk/essex_ob.html Leyton consisted of the manors of Marks, Ruckholt and Leyton and the arms are derived from the heraldry of the various holders of these.

The Manor of Marks belonged until 1545 to the Priory of St. Helens, it was then granted to Paul Withipole and his son, whose family is recalled by the lion passant from their arms.

The Church of Leyton was given by Gilbert Montfitchet to the Abbey and Convent of Stratford in 1134. The gift was confirmed by the Charter of Henry II in 1182, and later in 1200 the Manor of Leyton was also given to the Abbey. The Abbey of Stratford was founded in William Montfitchet in 1134 and the chevronels are from his family's arms.

The crozier is another reference to the Abbey of Stratford. Although the object in the crest is blazoned as a crozier it is usually depicted as a cross-staff, such as borne before an archbishop.

The Manor of Ruckholt was held until his death in 1417 by Sir Adam Frauncey, from whose arms comes the gold and black lion. The crozier is another reference to the Abbey of Stratford. Although the object in the crest is blazoned as a crozier it is usually depicted as a cross-staff, such as borne before an archbishop.

Where is the cross-staff? https://www.heraldry-wiki.com/wiki/Waltham_Forest

Tower Hill

[edit]The well publicised Fascist plan was for their marchers to gather at Tower Hill and the immediate surroundings at 2pm. As the first groups arrived at around 1:25,(REF???) they found Tower Hill held against them by roughly 500 counter-protesters.(EE then and now) A large group of Fascists entering Tower Hil from Mark Lane tube station was attacked by a group of counter-protesters making their way from Aldgate to Tower Hill, while two Fascists were attacked in Mansell Street as they made their way to Tower Hill.(ELA)

1:25 Source

Armoured Vans...

Moran injured

Police secure Tower Hill After it was over a variety of improvised weapons were picked up from the gutters.

Police then attempt to secure the junction (Aldgate reinforcements)

Bit later

A private car bearing the slogan "Mosley shall not pass" drove into Tower Hill and Fascists attacked it before it made its escape\drove off (ELA)(Pathe news)

fascists began to gather at Tower Hill from approximately 2:00 p.m. There were clashes between fascists and anti-fascists at Tower Hill and Mansell Street as they did so, while the anti-fascists also temporarily occupied the Minories.[11]

Sir Thomas More Street

[edit]Sir Thomas More Street, formerly Nightingale Lane, is a road in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It was formerly the course of a brook, one of the lost rivers of London, whose name has not been recorded.

Toponymy and renaming

[edit]The name Nightingale Lane is first known to have been recorded as Nechtingal Leane in 1543.[28] The name is thought to derive from the Cnihtengild, a brotherhood of local knights who owned the land that would become the parish of St Botolph without Aldgate.[29]

London County Council renamed the street in 193X as part of a major programme of renaming across the LCC area - the LCC wished to ensure street names were not duplicated in other parts of the capital. Sir Thomas More had no particular connection to the local area.(Ref Darby)

The brook

[edit]The source, or sources, of the brook aren't known for certain, but it may have risen at Wellclose Square. At or close to the Hermitage Entrance (to the London Dock) Brook at Nightingale Lane (modern Sir Thomas More Street)

boundary feature

[edit]Events

[edit]Swans Nest (MLS) - Hermitage given its name to a number of local features such as the Hermitage basin and the Hermitage Entrance

Mill (MLS)

King Charles and the Hunt (Wanstead)

1780 - Gordon Riots

1820 - Tom and Jerry

London Docks - St Katherines and London Docks

Around 1821 the writer Pierce Egan wrote a semi-autobiographical account of a visit to the Coach and Horses public house on Nightingale Lane (now called Sir Thomas More Street) in East Smithfield. The story tells of three upper class friends who tiring of high society events decide to “see a bit of life at the East End of Town”. Egan compares the East Ends informal egalitarian nightlife favourably to the formality of the West End.

every cove that put in his appearance was quite welcome, colour or country considered no obstacle...the group motley indeed; Lascars, blacks, jack tars, coalheavers, dustmen, women of colour, old and young, and a sprinkling of the remnants of once fine girls, &c. were all jigging together

— Pierce Egan, The True History of Tom & Jerry: or, Life in London (1821)[30]

A-S Essex

[edit]The Kingdom of the East Saxons included not just the subsequent county of Essex, but also Middlesex (including the City of London), much of Hertfordshire and at times also the sub-Kingdom of Surrey. The Middlesex and Hertfordshire parts were known as the Province of the Middle Saxons since at least the early eighth century but it is not known if the province was previously an independent unit that came under East Saxon control. Charter evidence shows that the Kings of Essex appear to have had a greater control in the core area, east of the Lea and Stort, that would subsequently become the county of Essex. In the core area they granted charters freely, but further west they did so while also making reference to their Mercian overlords.

"It has generally been assumed that the modern county's River Stour boundary with Suffolk represented a continuation of the old boundary between the Kingdom's of the East Saxons and East Angles. However studies of trade patterns and subinfeudation suggest that this was only the case at the estuary, and that inland the rest of the Stour catchment was united under the Kingdom of Essex." REFx2

Elsewhere

[edit]The church was badly damaged by enemy action in 1940, during the Blitz, and demolished in 1952. Its traced stone footprint and former graveyard remain, as part of Altab Ali Park.[31][32]

The area was part of the historic (or ancient) county of Middlesex, but military and most (or all) civil county functions were managed more locally, by the Tower Division (also known as the Tower Hamlets), a historic ‘county within a county’, under the leadership of the Lord-Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets (the post was always filled by the Constable of the Tower of London). The military loyalty to the Tower meant local men served in the Tower garrison and Tower Hamlets Militia, rather than the Middlesex Militia.[33][34]

Anglo-Saxon London Wall

[edit]Anglo-Saxon city revival

[edit]

From c. 500, an Anglo-Saxon settlement known as Lundenwic developed in the same area slightly to the west of the old abandoned Roman city.[35] By about 680, London had revived sufficiently to become a major Saxon port. However, the upkeep of the wall was not maintained and London fell victim to two successful Viking assaults in 851 and 886.[36]

In 886 the King of Wessex, Alfred the Great, formally agreed to the terms of the Danish warlord, Guthrum, concerning the area of political and geographical control that had been acquired by the incursion of the Vikings. Within the eastern and northern part of England, with its boundary roughly stretching from London to Chester, the Scandinavians would establish Danelaw.

Anglo-Saxon London Wall restoration

[edit]In the same year, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle recorded that London was "refounded" by Alfred. Archaeological research shows that this involved abandonment of Lundenwic and a revival of life and trade within the old Roman walls. This was part Alfred's policy of building an in-depth defence of the Kingdom of Wessex against the Vikings as well as creating an offensive strategy against the Vikings who controlled Mercia. The burh of Southwark was also created on the south bank of the River Thames during this time.

The city walls of London were repaired as the city slowly grew until about 950 when urban activity increased dramatically.[37] A large Viking army that attacked the London burgh was defeated in 994.[36]

Influence (to shorten)

[edit]Like most other city walls around England, the London Wall has been largely lost, though a number of fragments remain (see interactive map). The long presence of these walls had had a profound and continuing effect of the character of the City of London, and surrounding areas.[38] The walls constrained the growth of the city, and the location of the limited number of gates and the route of the roads through them shaped development within the walls, and in a much more fundamental way, beyond them. With a few exceptions, the parts of the modern road network heading into the former walled area are the same as those which passed through the former medieval gates.

Whitechapel's spine is the old Roman Road, that ran from the Aldgate on London's Wall, to Colchester in Essex (Roman Britannia's first capital), and beyond. This road, which was later named the Great Essex Road, is now designated the A11. This route has the names Whitechapel High Street and Whitechapel Road as it passes through, or along the boundary, or Whitechapel.[39] For many centuries travellers to and from London on this route were accommodated at the many coaching inns which lined Whitechapel High Street.[31]

Political tensions between Charles I and Parliament in the second quarter of the 17th century led to an attempt by forces loyal to the King to secure the Tower and its valuable contents, including money and munitions. London's Trained Bands, a militia force, were moved into the castle in 1640. Plans for defence were drawn up and gun platforms were built, readying the Tower for war. The preparations were never put to the test. In 1642, Charles I attempted to arrest five members of parliament. When this failed he fled the city, and Parliament retaliated by removing Sir John Byron, the Lieutenant of the Tower. The Trained Bands had switched sides, and now supported Parliament; together with the London citizenry, they blockaded the Tower. With permission from the King, Byron relinquished control of the Tower. Parliament replaced Byron with a man of their own choosing, Sir John Conyers. By the time the English Civil War broke out in November 1642, the Tower of London was already in Parliament's control.[40]

Political tensions between Charles I and Parliament in the second quarter of the 17th century led to an attempt by forces loyal to the King to secure the Tower and its valuable contents, including money and munitions. London's Trained Bands, a militia force, were moved into the castle in 1640. Plans for defence were drawn up and gun platforms were built, readying the Tower for war. The preparations were never put to the test. In 1642, Charles I attempted to arrest five members of parliament. When this failed he fled the city, and Parliament retaliated by removing Sir John Byron, the Lieutenant of the Tower. The Trained Bands had switched sides, and now supported Parliament; together with the London citizenry, they blockaded the Tower. With permission from the King, Byron relinquished control of the Tower. Parliament replaced Byron with a man of their own choosing, Sir John Conyers. By the time the English Civil War broke out in November 1642, the Tower of London was already in Parliament's control.[41]

History

[edit]Archaeological finds

[edit]In February 2022, archaeologists from the Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) announced the discovery of a well-preserved massive Roman mosaic which is believed to date from A.D. 175–225. The dining room (triclinium) mosaic was patterned with knot patterns known as the Solomon's knot and dark red and blue floral and geometric shapes known as guilloche.[42][43][44][45]

Archaeological work at Tabard Street in 2004 discovered a plaque with the earliest reference to 'Londoners' from the Roman period on it.

End of Roman Southwark

[edit]Londinium was abandoned at the end of the Roman occupation in the early 5th century and both the city and its bridge collapsed in decay. The settlement at Southwark, like the main settlement of London to the north of the bridge, had been more or less abandoned, a little earlier, by the end of the fourth century.[46]

Parishes in Middlesex were grouped into Hundreds, with Hackney part of Ossulstone Hundred. Rapid Population growth around London saw the Hundred split into several "Divisions" during the 1600s, with Hackney part of the Tower Division (aka Tower Hamlets). The Tower Division was noteworthy in that the men of the area owed military service to the Tower of London - and had done even before the creation of the Division.[47]

The area was part of the historic (or ancient) county of Middlesex, but military and most (or all) civil county functions were managed more locally, by the Tower Division (also known as the Tower Hamlets), under the leadership of the Lord-Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets (the post was always filled by the Constable of the Tower of London).

Cable Street

Spartacus background on mosley's growing A-S

Daily Worker - great Alie str

- In 1191 William Longchamp surrendered the Tower to Prince\King after a three day siege.

- In 1214 an under-strength garrison held the force for King John, against a hostile force led by Robert Fitzwalter.

- In 1267 Cardinal Ottobuon held the castle against a strong besieing army?

- In 1381 the castle was taken by around four hundred rebels during the Peasants Revolt. The gates were left open and the garrison did not content the entrance of the rebels.

- 1460 siege link

- In 1471, during the Siege of London, the Tower's Yorkist garrison exchanged fire with Lancastrians holding Southwark, and sallied from the fortress to take part in a pincer movement to attack Lancastrians who were assaulting Aldgate on London's defensive wall.

Tudor and Stuart actions

- In 1571 the Lieutenant of the Tower fired his cannon at City crowds engaged in the xenophobic Evil May Day riots, in which the properties of foreign residents were ransacked. It's not thought that any rioters were hurt by the gunfire, which was was probably meant to merely intimidate the mob.[48]

- Civil war (Skippon?)

Background

[edit]The British Union of Fascists (BUF) had advertised a march to take place on Sunday 4 October 1936, the fourth anniversary of their organisation. Thousands of BUF followers, dressed in their Blackshirt uniform, intended to march through the heart of the East End, an area which then had a large Jewish population.[49]

The BUF would march from Tower Hill and divide into four columns, each heading for one of four open air public meetings where Mosley and others would address gatherings of BUF supporters:[50][11]

- Salmon Lane, Limehouse at 5pm

- Stafford Road, Bow at 6pm

- Victoria Park Square, Bethnal Green at 6pm

- Aske Street, Shoreditch at 6:30pm

The Jewish People's Council organised a petition, calling for the march to be banned, which gathered the signature of 100,000 East Londoners, including the Mayors of the five East London Boroughs (Hackney, Shoreditch, Stepney, Bethnal Green and Poplar)[51][52] in two days.[5] Home Secretary John Simon denied the request to outlaw the march.[53]

Numbers involved

[edit]Very large numbers of people took part in the events, in part due to the good weather, but estimates of the numbers of participants vary enormously:

- Estimates of Fascist participants range from 2,000–3,000[21] up to 5,000.[11]

- There were 6,000–7,000 policemen, including the whole of the Metropoltan Police Mounted Division.[21][11][12] The Police had wireless vans and a spotter plane[11] sending updates on crowd numbers and movements to Sir Philip Game's HQ, established on a side street by Tower Hill.[11]

- Estimates of the number of anti-fascist counter-demonstrators range from 100,000[54][11] to 250,000,[55] 300,000,[56] 310,000[57] or more.[58]

Events

[edit]Tower Hill

[edit]The fascists began to gather at Tower Hill from approximately 2:00 p.m., there were clashes between fascists and anti-fascists at Tower Hill and Mansell Street as they did so, while the anti-fascists also temporarily occupied the Minories. The BUF set up a casualty dressing station in the Tower Hill area, as did their Independent Labour Party and Communist opponents who each had a dressing station.[11]

1:25 BUF begin to arrive but around 500 waiting for them - clashes (Then & Now) ELA says 2pm

1:40 Roughly 500 surged from Aldgate in the direction of the Minories (Then & Now)

At what point does the car 2pm, police begin to segregate the factions, heavy fighting and counter-protestors pushed into side streets like Dock Street (which led to St George's Highway) (Then & Now)

2:15 - at Aldate shouting "All to Cable Street" - many of whom went by way of leman Street (Then & Now) Assemble at 2?

Aldgate - Still clashes? Just after 3pm - Fenner Brockway makes call. (Battle for EE) 4pm - Headed west (Then & Now)

Other sites such as Limehouse etc (East London Adveriser) Speakers went on for two hours surrounded by police and then hecklers Defused when people told there was no march - close to 5pm 200 waited at Bow (ELA) Various meetings at Hoxton\Shoreditch (ELA)

Cable Street

[edit]Protesters built a number of barricades on narrow Cable Street and its side streets. The main barricade was by the junction with Christian Street, about 300 metres along Cable Street in the St George in the East area of Wapping. Just west of the main barricade, another barricade was erected on Back Church Lane; the barrier was erected under the railway bridge, just north of the junction with Cable Street.[59]

The Police attempts to take and remove the barricades were resisted in hand-to-hand fighting and also by missiles, including rubbish, rotten vegetables and the contents of chamber pots thrown at the police by women in houses along the street.[60]

Decision at Tower Hill

[edit]Mosley arrived in an open topped black sports car, escorted by Blackshirt motorcyclists, just before 3:30.[13] By this time, his force had formed up in Royal Mint Street and neighbouring streets into a column nearly half a mile long, and was ready to proceed.[13]

However, the police, fearing more severe disorder if the march and meetings went ahead, instructed Mosley to leave the East End, though the BUF were permitted to march in the West End instead.[5] The BUF event finished in Hyde Park.[61]

Arrests

[edit]About 150 demonstrators were arrested, with the majority of them being anti-fascists, although some escaped with the help of other demonstrators. Around 175 people were injured including police, women and children.[62][63]

Aftermath

[edit]The anti-fascists celebrated the community's united response, in which large numbers of East-Enders of all backgrounds; Protestants, Catholics and Jews successfully resisting Mosley. There were few Muslims in London at the time, so they were also delighted when Muslim Somali seaman join the anti-fascist crowds.[64]

The event is frequently cited by modern Antifa movements as "...the moment at which British fascism was decisively defeated".[65][66] The Fascists presented themselves as the law-abiding party who were denied free speech by a weak government and police force in the face of mob violence. After the event the BUF experienced an increase in membership, although their activity in Britain was severely limited.[67]

Following the battle, the Public Order Act 1936 outlawed the wearing of political uniforms and forced organisers of large meetings and demonstrations to obtain police permission. Many of the arrested demonstrators reported harsh treatment at the hands of the police.[68]

Long Ref [11] Short Ref: The Police had wireless vans[69]

next?

Legends around the Roding and lea

A legend St Erkenwald, Bishop of London (E - S)

St Æthelburh, abbess of Barking Abbey

- ^ "The Battle of Cable Street". cablestreet.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ a b "Cable Street". History Workshop. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Website shows the original BUF leaflet including exact locations and times

- ^ "Sir Oswald Mosley". Jewish Chronicle. 9 October 1936.

- ^ "ILP souvenir leaflet". Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Sir Philip Game. "'No pasarán': the Battle of Cable Street". National Archives. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ Piratin, Phil (2006). Our Flag Stays Red. Lawrence & Wishart. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-905007-28-8. cited by Smith, Lottie Olivia (July 2021). Exploring Anti-Fascism in Britain Through Autobiography from 1930 to 1936 (PDF) (MRes). Bournemouth University. p. 72.

- ^ "The Battle of Cable Street". cablestreet.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Sir Oswald Mosley". Jewish Chronicle. 9 October 1936.

- ^ "ILP souvenir leaflet". Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Piratin, Phil (2006). Our Flag Stays Red. Lawrence & Wishart. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-905007-28-8. cited by Smith, Lottie Olivia (July 2021). Exploring Anti-Fascism in Britain Through Autobiography from 1930 to 1936 (PDF) (MRes). Bournemouth University. p. 72.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Lewis, Jon E. (2008). London, The Autobiography. Constable. p. 401. ISBN 978-1-84529-875-3. Lewis uses the East London Advertiser as primary source, and also provides editorial commentary. This source only gives the districts where the meetings would take place, not times or the exact locations. Cite error: The named reference "London, The Autobiography" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c d e f g Ramsey, Winston G. (1997). The East End, Then and Now. Battle of Britain Prints International Limited. pp. 381–389. ISBN 0 900913 99 1. Cite error: The named reference "The East End, Than and Now" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b c "Fascist march stopped after disorderly scenes". Guardian newspaper. 5 October 1936. Retrieved 18 April 2022.

- ^ "The Battle of Cable Street". cablestreet.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Cable Street". History Workshop. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Website shows the original BUF leaflet including exact locations and times

- ^ "Sir Oswald Mosley". Jewish Chronicle. 9 October 1936.

- ^ "ILP souvenir leaflet". Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Piratin, Phil (2006). Our Flag Stays Red. Lawrence & Wishart. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-905007-28-8. cited by Smith, Lottie Olivia (July 2021). Exploring Anti-Fascism in Britain Through Autobiography from 1930 to 1936 (PDF) (MRes). Bournemouth University. p. 72.

- ^ "Cable Street". History Workshop. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Website shows the original BUF leaflet including exact locations and times

- ^ Rosenburg, David (2011). The Battle for the East End. Five Leaves Publications. p. Chapter 8. ISBN 978-1-907869-18-1.

- ^ a b c d Jones, Nigel, Mosley, Haus, 2004, p. 114

- ^ Marr, Andrew (2009). The Making of Modern Britain. Macmillan. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-230-70942-3.

- ^ "The official interpretation board at the Cable Street mural". Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Independent Labour Party leaflet". Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Daily Chronicle, cited in a TUC Book on Cable Street" (PDF). pp. 11–12. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "TUC Book on Cable Street" (PDF). pp. 11–12. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

It makes reference to contemporary estimates as high as half a million, but does not give a primary source.

- ^ Waeppa's People – a History of Wapping by Madge Darby – ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- ^ The Place Names of Middlesex - English Place name Society - Vol 18 - Gover Maw and Stenton - Cambridge University Press - p157 - 1942

- ^ Waeppa's People – a History of Wapping by Madge Darby – ISBN 0-947699-10-4

- ^ Egan P, The True History of Tom & Jerry: or, Life in London, London, Charles Hindley, 1821 https://www.gutenberg.org/files/43504/43504-h/43504-h.htm

- ^ a b Ben Weinreb and Christopher Hibbert (eds) (1983) "Whitechapel" in The London Encyclopaedia: 955-6

- ^ Andrew Davies (1990) The East End Nobody Knows: 15–16

- ^ The London Encyclopaedia, 4th Edition, 1983, Weinreb and Hibbert

- ^ East London Papers, Volume 8, Number 2, The Name 'Tower Hamlets'. M.J. Power, December 1965

- ^ "The early years of Lundenwic". Museum of London. Archived from the original on 10 June 2008.

- ^ a b Wheeler, Kip. "Viking Attacks". Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ^ Vince, Alan (2001). "London". In Lapidge, Michael; Blair, John; Keynes, Simon; Scragg, Donald (eds.). The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Anglo-Saxon England. Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-22492-1.

- ^ Citadel of the Saxons, the Rise of Early London. Rory Naismith, p31

- ^ 'Stepney: Communications', A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 11: Stepney, Bethnal Green (1998), pp. 7–13 accessed: 9 March 2007

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 74

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, p. 74

- ^ Jeevan Ravindran. "London's largest Roman mosaic in 50 years discovered by archaeologists". CNN. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Sharp, Sarah Rose (2022-02-24). "Large Roman Mosaic Discovered in Central London". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Goldstein, Caroline (2022-02-24). "Digging in the Shadows of London's Shard, Archaeologists Discovered a 'Once-in-a-Lifetime Find': a Shockingly Intact Roman Mosaic". Artnet News. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Solomon, Tessa (2022-02-24). "Archaeologists Uncover London's Largest Roman Mosaic in 50 Years". ARTnews.com. Retrieved 2022-02-27.

- ^ Citadel of the Saxons, Rory Naismith p 35, 2019

- ^ The London Encyclopaedia, 4th Edition, 1983, Weinreb and Hibbert

- ^ John Edward Bowle, Henry VIII, 1964

- ^ hate, HOPE not. "The Battle of Cable Street". www.cablestreet.uk. Archived from the original on 27 May 2018. Retrieved 16 May 2018.

- ^ "Cable Street". History Workshop. 8 January 2011. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

Website shows the original BUF leaflet including exact locations and times

- ^ "Sir Oswald Mosley". Jewish Chronicle. 9 October 1936.

- ^ "ILP souvenir leaflet". Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- ^ Piratin, Phil (2006). Our Flag Stays Red. Lawrence & Wishart. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-905007-28-8. cited by Olivia, Lottie Smith (July 2021). Exploring Anti-Fascism in Britain Through Autobiography from 1930 to 1936 (PDF) (MRes). Bournemouth University. p. 72.

- ^ Marr, Andrew (2009). The Making of Modern Britain. Macmillan. pp. 317–318. ISBN 978-0-230-70942-3.

- ^ "The official interpretation board at the Cable Street mural". Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Independent Labour Party leaflet". Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "Daily Chronicle, cited in a TUC Book on Cable Street" (PDF). pp. 11–12. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

- ^ "TUC Book on Cable Street" (PDF). pp. 11–12. Retrieved 17 June 2022.

It makes reference to contemporary estimates as high as half a million, but does not give a primary source.

- ^ "Recollections and sketches of James Boswell". Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- ^ "Torah For Today: The Battle of Cable Street". Jewish News. 30 April 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Eight decades after the Battle of Cable Street, east London is still united". The Guardian. 16 April 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Brooke, Mike (30 December 2014). "Historian Bill Fishman, witness to 1936 Battle of Cable Street, dies at 93". News. London. Hackney Gazette. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ^ Levine, Joshua (2017). Dunkirk : the history behind the major motion picture. London. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-00-825893-1. OCLC 964378409.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Wadsworth-Boyle, Morgan. "The Battle of Cable Street". https://jewishmuseum.org.uk/. Retrieved 2023-11-09.

{{cite web}}: External link in|website= - ^ Penny, Daniel (2017-08-22). "An Intimate History of Antifa". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2017-08-26.

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

:0was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Webber, G.C. (1984). "Patterns of Membership and Support for the British Union of Fascists". Journal of Contemporary History. 19 (4). Sage Publications Inc.: 575–606. doi:10.1177/002200948401900401. JSTOR 260327. S2CID 159618633. Retrieved 2 December 2021.

- ^ Kushner, Anthony and Valman, Nadia (2000) Remembering Cable Street: fascism and anti-fascism in British society. Vallentine Mitchell, p. 182. ISBN 0-85303-361-7

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

The East End, Then and nowwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ The East End then and Now, Winston G Ramsey, Battle of Britain Prints International Limited. 1997, ISBN 0 900913 99 1, p381-389