User:Beatrizsborges/sandbox

|

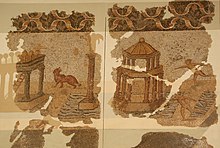

The Carthage Circus Mosaic is a Roman mosaic dating from the 1st or 2nd century, discovered

on the archaeological site of Carthage, in present-day Tunisia, in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Little is known about the archaeological context of the find, with archaeologists concentrating on the object itself, and little is known about the building that contained it, although it may have been a domus, given its location not far from a residential area now being developed as part of an archaeological park.

The work depicts both a circus seen from the outside and the show inside, offering a double perspective of the building and a representation unique in ancient mosaic art. The mosaicist depicted the building and its characters distortedly but in accordance with the aesthetic criteria of his time. The scene depicts a circus race coming to an end, a snapshot of the moment of victory for the Les Bleus team.

The mosaic, deposited in the Bardo National Museum immediately after its discovery, is considered by most specialists to be a representation of the city's circus, which left only faint traces on the archaeological site. This edifice in the capital of the African province was partially excavated in the 20th century, and the mosaic provides a plausible representation of the building. In particular, an exhaustive study of the way in which certain elements, such as the spina, were depicted, makes it possible to link the edifice to a series found in other cities in Roman Africa with the same type of entertainment building.

History and location[edit]

The mosaic is one of the important pieces on display at the Musée National du Bardo, located in the suburbs of Tunis, as part of the presentation of circus games.

Ancient history[edit]

According to Jean-Claude Golvin and Fabricia FauquetM 1,[1] the work dates "at the earliest" from the 1st century; according to Hédi Slim,[2] from the late 1st or early 2nd century; and according to Aïcha Ben Abed,[3][4] from the 2nd century. Representations of entertainment buildings in the mosaics of provincial cities were undoubtedly inspired by nearby buildings.[5] According to Mohamed Yacoub,[6] the mosaics were the work of local artists.

The archaeological context is not well known, as the room was "poorly excavated "A 1. The mosaic was located in a small room interpreted as the vestibuleA 1,M 2[7] within a building whose function is not specified, although it probably belonged to a domus, located in the area of a residential quarter, part of which is now preserved in the archaeological park of Roman villas.

Rediscover[edit]

The mosaic was found on the Odéon hillL 2 ,[8] a hundred meters from the theater and the Odéon, in March 1915, "at the bottom of the Dahr-Morali plot "A 1. Following Alfred Merlin's intervention, it immediately joined the collections of the Musée du BardoA 1. The publication of the mosaic in 1916 gave no further details on the context of its discovery.

In the 1980s, the mosaic was identified as a combination of amphitheater and circus, and this theory was subsequently taken up by a number of specialists, including John H. HumphreyM 3.[9] However, it was rejected by several specialists in circus games and performance buildings, including Mohamed Yacoub and Jean-Claude Golvin, as no building of this combined form has been attested in the Roman EmpireM 4.[10] Fights have indeed been documented in circuses, but amphitheaters could not have been used for racesL 3,[11] as "the arena of an amphitheater [was] ridiculously small for even small-scale races to have been organized there "M 3.

Description[edit]

The mosaic depicts the circus building and what happens in the ring.

Composition[edit]

Measuring 2.70 m by 2.25 m,[12] the mosaic is composed of marble and glass tesserae, the smallest being glass. The border is 0.20 mA 1 wide.

The artist uses perspective to show three sides of the buildingA 2. A semblance of the building's shadow is shown, as well as the figures and quadrigas on the track, the shadow coming from the left of the buildingA 3.[13] The perspective used, "conventional with several points of view "C 1,[14] is aerial and oblique: it is the spectators' point of view that is adopted for the vision of the building's interiorF 1.[15]

Its composition seems dictated by the layout and function of the room in which the work was found, and the presence of two doors, one to the south providing access to the building, the other to the westL 5,M 2.[16][17] For the artist, the aim was to "[accompany] [...] the turning movement that one would necessarily make when crossing the room "M 2 between the two doors, south and west, the curves being intended to accentuate itL 5.[18]

Description of the exterior building[edit]

The cirque de Carthage faces north-west-south-east and, according to Léopold-Albert Constans, "the moment chosen by the artist corresponds to the early hours of the afternoon "A 3.[19]

The building is massiveF 1,[20] with two storeysD 2,J 1[21][22] of arcaded galleries[23]M 5 and an atticJ 2, 32 arched openingsA 2 and two towers seen from the frontC 1. The roof of the top floor is also shown by Fabricia FauquetL 6.[24]

According to some specialists, including Léopold-Albert Constans and Mohamed Yacoub, on three of the sides is a velum designed to protect spectators from the sun or bad weatherC 1, while the last side is not shown, either because this façade was oriented so as not to need it, or because of an artistic choice designed to show the tiers of the performance buildingA 3. Only the spectators are protected, not the trackA 4. The velum's fastening system is also shown: it comprises transverse ropes with a horizontal separationA 4.[25] The mosaicist would have depicted the details of the fastening system according to Léopold-Albert Constans, with rings connected to pulleys and masts located in the upper parts of the buildingA 5. More recent research, such as that by Fabricia Fauquet and Jean-Claude Golvin, refutes the existence of such a velum, due to the absence of rings allowing such an installation to be hung on equipment whose track would be too wideL 2,M 5.[26][27] The roof of the carceres would have been made of tilesL 7,M 1[28][29] and that of the cellaraL 8,[30] pink and red in colorM 2.[31]

At the bottom of the side from which the bleachers can be seen, the artist has depicted the seven vomitoriesA 5.[32] These vomitories are designed to lead spectators to their seatsF 1. Unusually, the artist has not depicted any spectators in this part of the buildingC 1.

As the two buildings above the cavea are tetrastyle and pedimented, Leopold-Albert Constans identifies them as temples. The Circus Maximus, the Circus FlaminiusA 6[33] and the Theater of Pompey all feature cult buildings. According to Mohamed Yacoub, these aediculae may have been referees' boxesC 1 or temples, although specialists are divided on the subjectF 1. One of the buildings would be the pulvinar and the other a temple "dedicated to a major circus deity" according to Jean-Claude GolvinJ 3,[34] or SolL 8.[35] The editoris tribunal is not representedM 6.[36]

There are also eight carceres to the north-west of the building, divided into two sections: the carceres are enclosed by gates and clerestory doorsC 1, and a wide passage separates the two sections. At the opposite end of the building is a triumphal gatewayA 7,F 1.[37] The mosaic shows the porta pompæ wide open and larger than the carceresM 3. Current experts on the building believe that there were twelve carceres and a porta pompæ similar to that in the circus of MaxentiusL 6,M 3.[38] The mosaic does not depict any towers, known as oppida, although such installations have been identified on some circuses, such as that of Maxentius, but were not attested until the fourth centuryL 9,M 1.[39] Similarly, the representation does not include a secondary lodge built above the carceresL 10.[40]

Description of the runway and the show[edit]

The representation of the spina is only partly preserved on the rightA 7 and divides the space representing the showF 2 in two. By symmetry, Jean-Claude Golvin and Fabricia Fauquet were able to propose a reconstruction of the representation of this lost part of the mosaicM 6.[41]

The central spina, which ends in a semicircle, stands out on the track, as does a bollard made up of three cones, the meta secunda, placed on a baseL 4,M 6. In the middle of the spina is not an obelisk, as in RomeC 1, but a statue identified with Cybele seated on a lionJ 1, even though it has been partially lost; this divinity presides over chariot races. While traces of her crown remain, she holds a sceptre in one arm and the other is outstretched, perhaps towards the end of the raceA 8.[42] The mosaic in Piazza Armerina, like the one in Barcelona, suggests the presence of an obelisk and a statue of Cybele for the Circus MaximusL 11.[43] The mosaic from the Villa of the Bull at Silin in Tripolitania shows only a representation of Cybele on a lion and refers to an "African circus", perhaps that of Leptis Magna, where the remains of a base that may have belonged to a monumental statue of a lion have been foundM 7.[44] The statue of Cybele is in the middle of the spina on the mosaicL 12, testifying to the divinity's "prime importance in Africa "M 7.

There are also basins on the spinaF 2. The podium of the spina has a concave shape at the endL 4. The meta prima was located in the lacuna present on the workL 4. In addition to the insured elements, the spina included a round temple and "one or two elements", perhaps a chapel and a monumental columnL 13,M 7.[45] The spina was richly decorated with statuesL 1.

One column has a statue of Victory that has disappearedM 6. Two other columns bear an architrave with a tower-counting system made up of seven dolphinsF 2. Parallel to this, in the gap in the mosaic, must have been an architrave bearing seven eggsA 9.[46] After the columns is a hexagonal aedicule called a fala by ConstansA 10,L 14.[47][48] The revolution counter system, a "dolphin monument", was in the form of a gallowsL 11 as on the Silin mosaicM 6. The elements depicted on the mosaic are also present on the "iconography of the Circus Maximus", but a gap prevents us from confirming the presence of an obeliskJ 4. The building may have included "egg aediculae", which are included in the gap in the mosaic and have been documented on the Silin mosaic, the Lyon mosaic and the remains of the Merida spinaL 11.

Around the bollard run four quadrigas, one of which is going in the opposite direction to the othersD 3,C 2.[49] Three quadrigas are going from right to left, and one of them is stoppingA 11.[50] The quadriga that has completed the seven lapsC 2 is the winner: it wears a palmA 12[51] and has the reins around its waistF 2. The charioteers wear a helmet with a crest and the harnessed horses have a plume of feathersA 12.

When the creta, the finishing line on which the referees stood, was crossed, the winner had to make a U-turn to be presented with the palm by a magistrate and prepare to parade in front of the standsE 1;[52] he then had to return to the carceres, to the left of the entrance gate: the charioteer in the mosaic stands back to slow his horses and prepares to ride around the meta secundaA 13.[53] A rider is standing in front of the winning quadriga: this is the jubilator or hortator (or, according to Mohamed Yacoub, the propulsorF 2), whose job it is to encourage the winnerA 12.

The quadriga that came second was in the process of stopping, "with its body leaning heavily backwards "F 3 ,[54] and joining the carceres, but had to stop at the invitation of a figure holding an amphora and a whip, a "track official "F 4 , the morator ludi according to Léopold-Albert Constans or a sparsor according to Mohamed YacoubC 2 : This person stops the quadriga by spraying the axles of the chariot and cares for the equines, giving them water to cool their nostrils. On the opposite side of the track, another morator (or sparsor), partially preserved, stops a quadriga whose driver raises his arm in acceptance of defeat. This is a normal intervention, as "the outcome of the race was already known "C 2. The third quadriga appears to be whipping its horses, hoping to win a placeA 14.[55]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 286)

- ^ Slim & Fauqué (2001, p. 182)

- ^ Ben Abed-Ben Khedher (1992, pp. 62–63)

- ^ Hassine Fantar, Aounallah & Daoulatli (2015, p. 118)

- ^ Constans (1916, p. 249)

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 429)

- ^ Golvin & Fauquet (2003, p. 287)

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ Fauquet (2002, p. 426)

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]

- ^ [[#CITEREF|]]