User:Cdjp1/sandbox/sleih beggey

https://eu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bozate Bozate is a neighborhood in the town of Arizkun in the municipality of Baztan, Navarre.

It is located in the Merindad de Pamplona and 56.9 km from the capital city of Navarre, Pamplona. Its population in 2017 was 96 inhabitants.[1]

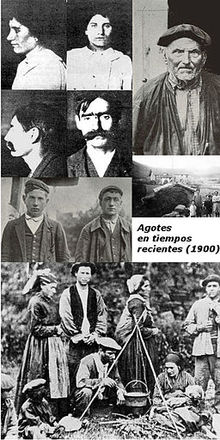

It is famous for having been the last known enclave of a population of Agotes in Spain, a social group discriminated against for obscure reasons. The neighborhood is home to the Museo Etnográfico de los Agotes (Ethnographic Museum of the Agotes), promoted by the Navarrese sculptor Xabier Santxotena Alsua.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xabier_Santxotena_Alsua https://eu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Xabier_Santxotena Xabier Santxotena Alsua (born 5 October 1946, Bozate, Navarre) is an Agote sculptor and poet and researcher of Agotes.

Biography

[edit]Xabier Santxotena Alsua was born to a family of Agote craftsmen - a group discriminated against for centuries for unclear reasons. He was trained as a carpenter, like his father or his maternal grandfather.

While Jorge Oteiza was displaying his work of the apostles in the Sanctuary of Arantzazu, he met Santxotena in the cafe that Santxotena ran at the time in Zumárraga and was impressed by the low-relief carvings that Santxotena made. As a result of this, Oteiza encouraged and supported Santxotena's development as a sculptor.

Museums

[edit]In 1998, in the family home of Xabier Santxotena with the support of the painter Teresa Lafragua they conceived the first museum in the Bozate de Arizcun neighborhood called Gorrienea. This first museum is a tribute to the exhausts .

The second museum saw the light in 2003 also in the Bozate neighborhood. It is a sculpture park about art and nature from Basque mythology. In this museum the work of Xabier Santxotena is displayed as a monumental sculpture in wood, steel, bronze and concrete.

The third Santxotena museum is located in the Alavesa de Arceniega town and opened in 2010. This museum was born as a workshop where the work begins and is finally exhibited. The work on display is monumental and the sketches of all the sculptor's historical work are also displayed.

https://eu.wikipedia.org/wiki/Santxotena_Museoa

Caquins de Bretagne

[edit]In parish records of births, they were listed at the end, upside-down with illegitimate children.[2]

Pages to translate

[edit]Sacred Spain Trasterminance Navarrese Romance Pasiego Maragato

Franz Xaver von Zach : Some news from the Cagots in France

[edit]https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/rsc/viewer/jportal_derivate_00200951/AGE_1798_Bd01_0509.tif

|author-first=Franz Xaver |author-last=von Zach |author-link=Franz Xaver von Zach |title=Einige Nachrichten von den Cagots in Frankreich |language=de |trans-title=Some news from the Cagots in France |journal=Allgemeine geographische Ephemeriden |volume=1 |number=5 |date=March 1798 |pages=509–524 |url=https://zs.thulb.uni-jena.de/rsc/viewer/jportal_derivate_00200951/AGE_1798_Bd01_0509.tif

German

[edit]Der Stolz der vornehmen, und die Geringschätzung der niedrigen Classen scheint, aller Geschichte zu Folge, mit dem Unterscheide der Stände von gleichem Alter zu seyn, und entsteht aus sehr natürlichen Ursachen und Gründen. Auch hat es, seitdem es Kriege und Eroberer gibt, Knechte und Leibeigene gegeben, welche zu verschiedenen Zeiten und bey verschiedenen Völkern nicht selten mit einer ausserordentlichen Härte behandelt wurden. Selbst in der vollkommensten aller politischen Verfassungen, in der Spartanischen Staatsverwaltung, werden wir in Hinsicht auf ihre Iloten Verfügungen gewahr, welche unser Gefühl von Menschlichkeit empören, und mit der mit Recht gerühmten Weisheit dieses Staates in einen sonderbaren Widerspruche stehen. Diess also, dass ein Mensch dem andern dient und unterworfen ist, dass die Herrschsucht keine Gränzen kennt, darf niemand befremden. Immer hat der Stärkere sich des Schwächern bemächtigt, und die Regierung soll noch gefunden werden, in welcher aller Unterschied zwischen Starken und Schwachen verschwindet. Dieser Unterschied, und mit ihm die Unterdrückung des einen Theils werden auch für künstige Zeiten, wie es scheint, so lange fortdauern, als es Menschen von ungleichen Kräften und Anlagen, sammt einem Eigenthum gibt - Hindernisse, welche nicht so leicht gehoben werden können. Aber dass ein Volk gegen einen ansehnlichen Theil seiner Mitbürger in seinem Hasse und Abscheu und in seiner Verachtung so weit gehen könne, dass es eben diese Menschen nicht einmahl der Unterjochung und Knechtschaft würdig halte; dass es ihnen aus dieser Ursache die ersten und wesentlichsten Menschen-Rechte verweigere; dass diess sogar unter sehr policirten Nationen geschehe, - diese Erscheinung ist so sonderbar und auffallend, dass sie kein Mensch vermuthen sollte, wenn sie nicht leider! eine Thatsache wäre. Sie ist zu gleicher Zeit von der Art, dass sie für den Philosophen sowohl, als für den Geschichtforscher ein sehr verwickeltes Problem darbietet, dessen Auflösung seinen Schafsinn von mehr als einer Seite hinlänglich beschäftigen kann.

Diese geographische Seltenheit finden wir zuerst in Indien. Es muss unsern Lesern aus Sonnerat* und andern Reisebeschreibern eine sehr bekannte Sache seyn, in welchem Zustande der tiefsten Erniedrigung und Verachtung in Hindostan die Parias, oder, wie eben diese Elenden an der Küste von Malabar heissen, die Puliats leben. Sie find es, aus welchen die letzte der Indischen Casten besteht; von welchen, sehr gegründeten Vermuthungen zu Folge, das in allen Europäischen Ländern so berüchtigte Volk der Zigeuner seinen Ursprung ableitet.

Diese Caste ist der Auswurf aller übrigen. Nichts geht daher über die Verachtung, welche sie erfahren. Nichts würdigt so sehr herab, als der Umgang mit dieser Gattung von Menschen. Die Europäischen Missionarien sind dadurch sammt ihrer Lehre dem Indier zum Scheusal geworden. Die Menschen, aus welchen diese Caste besteht, verrichten die niedrigsten und ekelhaftesten Dienste. Sie begraben die Todten, sie schaffen allen Koth und Unrath hinweg; sie nähren sich sogar vom Fleische gefallener Thiere. Diess verursacht, dass sie von allen übrigen getrentt leben. Sie dürfen nie unter andern Menschen, und nur im höchsten Nothfalle vor ihrem Herrn, aber allezeit, wie sich versteht, in hinlänglicher Entfernung erscheinen, und nicht anders sprechen, als indem sie die Hand vor den Mund Bringen. Hat ein Paria Verrichtungen in einem Hause, so kann er nicht anders, als durch eine eigens dazu bestimmte Thüre, und mit niedergeschlagenen Augen in das Haus kommen. Würde man bemerken, dass er einen Blick in die Küche geworfen, so müsste augenblicklich alles vorhandene Geschirr zerschlagen und hinausgeworfen werden. Sogar der Gebrauch der Gemeinde-Brunnen bleibt ihnen untersagt. Sie haben in der Nähe von den Wohnungen ihrer Herren eigene Wohnungen, unter der Verbindlichkeit, dass sie Thierknochen umherstreuen, auf dass jeder anderesie daren erkenne und vermeide. Sie leben entweder in elenden Hütten auf dem Felde zerstreut, oder am äussersten Ende der Stadt. Sie können sich zwar gleich den übrigen Indiern auch auf den Ackerbau legen, aber nie ein Felm eigenthümlich besitzen oder in Pacht nehmen. Der Abscheu gegen diese Unglücklichen geht so weit, dass sie Gefahr laufen, selbst das Leben zu verlieren, sobald sie auch nur von ungefähr einen andern berühren. So wenig habeu selbst die Gesetze für ein Leben gesorgt, welches zu gering scheint, als dass es ihre Aufmerksamkeit verdienen sollte. Man sollte glauben, dass eine so empörende Unterscheidung wenigstens in den der Gottheit geweiheten Tempeln aufhören würde, an diesen Orten, wo all Menschen ohne Ausnahme als Kinder eines gemeinschaftlichen Vaters und folglich als Brüder erscheinen, wo daher mit grossem Rechts alles, was an Unterscheidung erinnert, hinweg fallen sollte. Aber wie wollen wir, um billig zu feyn, von dem Aberglauben der Indier eine Wirkung erwarten, welche eine bessere Überzeugung in den Gemüthern der Europär noch lange nicht bewirkt hat? auch in den Tempeln der Europäischen Christen erinnert der Luxus der Grossen und Reichen den Unvermögenden und Schwachen nur zu sehr an seine Niedrigkeit und Schwäche. Was Wunder also, dass den Indier seine groben unbesiegten Vorurtheile noch weiter treiben, dass er seine Tempel den Parias verschliesst, und sie der Beobachtung aller gottesdienstlichen Gebräuche und Pflichten entledigt und davon freyspricht? Was Wunder, dass es in der Meinung der vornehmern Indier für solche Menschen so wenig einen Gott und eine Kirche, als eine Seligkeit und einen Staat gibt?

Noch tiefe ist die Erniedrigung, in welcher die Puliats and der Küste von Malabar leben. Diese letzten beschäftigen sich mit dem Reifsbau. Nahe an den Feldern, welche sie bearbeiten, steht eine niedrige Hütte, in welche sich der Puliat beym geringsten Geräusch von der Annäherung seines Eigenthümers flüchten und verbergen muss. In dieser versteckt, hört er seine Befehle und Aufträge, und antwortet, ohne seinen Zufluchtsort zu verlassen. Diese Vorsicht ist die nämliche, so oft sich, wer nur immer, seinem Bezirke nähert. Er muss sich sogar zur Erde auf das Angesicht werfen, im Falle er so schnell überrascht würde, dass er nicht sogleich entfliehen könnte. Wenn die Erndte der Habsucht und Gierigkeit seines Eigenthümers nicht entspricht, so legt dieser nicht selten Feuer an sein Haus und drückt sogar sein Gewehr auf ihn los, wenn er es versuchen wollte, den Flammen zu entgehen. Die Art, mit welcher man diese herabgewürdigten Menschen nöthigt, für ihre dringendsten Bedürfnisse zu sorgen, ist nicht weniger schrecklich. Mit dem Anbrechen der Nacht kommen sie in mehr oder weniger zahlreichen Hausen, nähern sich dem Markt-Platze, und fangen in einiger Entfernungn füchterlich zu heulen an. Auf dieses Signal nähern sich die Verkäufer, und die Puliats verlangen, was und so viel sie benöthiget sind. Man befriedigt ihre Wünsche, indem man die Waare an die Stelle hinlegt, an welcher von ihrer Seite der Werth baar hingelegt worden. Die Liebe zum Gelde macht, dass der Kaufmann sich über alle Vorurtheile hinwegsetzt und den Betrag ohne Scheu zu sicht nimmt. Sobald die Käufer glauben, dass sie ungesehlen erscheinen können, treten sie aus ihrem Hinterhalte hervor, und ergreifen mit grosser Hastigkeit, was sie auf diese sonderbare Weise erhalten haben.

Aber auch diese so tief gebeugten Menschen - wer sollte es glauben, auch sie verfolgen ihres Gleichen, und dünken sich besser, als anere aus ihrem Mittel zu feyn. So sehr hat selbst der Elendestem si weit es möglich ist, einen noch Elendern nöthig, um nicht alles Gefühl seiner selbst zu verlieren! So sehr verfolgt die Begierde über andere zu herrschen, und der Wunsch, etwas vorzustellen und zu feyn, jeden Menschen in allen Ständen, durch alle Situationen des Lebens! Diese Elenden, welche allen übrigen ein Scheusal sind, auch diese Menschen find nicht frey von Casten-Stolz, und stossen einige aus ihrem Mittel aus. Diesen ausgesonderten, welche Pulichis heissen, ist sogar der Gebrauch des Feuers untersagt. Eben so wenig wird ihnen gestattet, sich Hütten zu bauen. Sie sind daher gezwungen, entweder in Höhlen, oder in den Wäldern auf Bäumen zu wohnen. Hier heulen sie vom Hunger gepeinigt, gleich den wilden Thieren, um das Mitleiden der Vorübergehen den zu erwecken. Diese bringen sodann Reiss oder andere Nahrung an den Ort, und entfernen sich in möglicher Eile, damit der Hungernde danach greifen könne, ohne seinem Wohlthäter zu begegnen, welchen er durch seine Gegenwart verunreinigen würde.

Raynal, aus dessen Histoire philosophique et politique etc. ich die meisten dieser Nachrichten geschöpft habe, nennt diese sonderbare Erscheinung ein unauflösliches Räthfel, mit dessen Auflösung sich bisher der Geist der scharfsehendsten Menschen vergeblich beschäftiget habe. *) Er versucht eine eigene Erklärung, welche sinnreich, aber nicht über alle Zweifel und Einwürfe erhaben ist. Er glaubt, alle Parias seyen ursprünglich von den übrigen Casten ausgestossene Verbrecher. Es kommt darauf an, ob diese Meinung mit Thatsachen aus der Indischen Geschechte könne belegt werden. Aber selbst in diesem Falle würde, da jede Rehabilitation ohne Beyspiel ist, dieses Verfahren angeerbt und nicht angeerbt und nicht minder grausam, als die Todesstrafe seyn, indem die Schnuldlosen Nachkommen dieser Verbrecher bis in die entferntesten Generationen mit gleicher Strafe belegt werden.

Doch hier ist der Ort nicht, diese Meinung zu prüfen. Verwundern müssen wir uns vielmehr, wie es einem nem Raynal entgehen konnte, dass ähnliche Dinge in Europa, dass sie sogar in seinem Vaterlande, unter seinen Augen geschehen; dass auch Frankreich seine Parias hat. *)*) Auch der Druck und die Verachtung, in welcher in den meisten Ländern von Europa die Juden leben, scheint hierher zu gehören und verdient auf gleiche Art gerügt zu werden.

(Page 516) An der westlichen Küste dieses Landes, von St. Malo an, bis tief die Pyrenäen hinauf, befindet sich eine Classe von Manschen, welche den Indischen Parias sehr nahe kommt, und mit diesen auf gleicher Stufe der Erniedrigung steht. Sie leben in diesen Gegenden zerstreut, seit undenklichen Zeiten bis auf den heutigen Tag unter fortdauernder Herabwürdigung von Seiten ihrer mehr begünstigten Mitbürger. Sie heissen mit ihrer bekanntesten und allgemeinsten Benennung Cagots, und es bleibt zweifelhaft, ob die Heuchler ihnen, oder sie diesen ihren Namen mitgetheilt haben, obgleich das letzte mir glaublicher scheint. Man findet sie nicht allein in gebirgigen Ländern, sondern auch in den flachen Gegenden dieses Reichs, ein Umstand, welcher nicht übergangen werden darf, indem sie sich dadurch von den Cretins oder den Walliser Tölpeln merklich unterscheiden, und nicht, wie einige dafür halten, mit diesen verwechselt werden können. Man kennt sie in Bretagne unter der Benennung von Cacous oder Caqueux. Man findet sie in Aunis, vorzüglich auf der Insel Maillezais, so wie auch in La Rochelle, wo sie Coliberts gennent werden. In Guyenne und Gascogne in der Nähe von Bordeaux erscheinen sie unter dem Namen der Cahets, und halten sich in den unbewohnbarsten Morästen, Sümpfen und Heiden auf. In den beyden Navarren heissen sie Caffos, Cagotes, Agotes. Am hänfigsten werden sie in den Thälern von Comminges, Bigorre und Bearn, vorzüglich im Luchoner-Thal gefunden. Ungeachtet diese Elenden durch einen ansehnlichen Strich von Frankreich zerstreut leben, so ist doch ihr Daseyn, wie das oben angeführte Beyspiel von Raynal beweist, selbst vielen Franzosen, welche nicht aus jenen Gegenden sind, gänzlich unbekannt. Die Nachrichten und Zeugnisse von diesen Menschen in Büchern und Schriftstellern sind daher äusserst selten und sparsam. Ja, wenn wir einige zerstreute Winke, welche in öffentlichen Urkunden vorkommen, abrechnen, so lassen sich alle Nachrichten davon nur aus zwey Quellen herleiten. Die erste und älteste Quelle ist die Histoire de Bearn par Pierre de Marca L.1. Chap/16. Was in Menage Dictionnaire etymologique unter dem Artikel Cagot vorkommt, ist wörtlich aus dieser Quelle genommen. Die neuesten, und wie man von einem Augenzeugen vermuthen kann, auch die zuverlässigsten Nachrichten vom J. 1787. verdanken wir Ramond in seinen Reisen nach den Pyrenäen. Die Verfasser der Encyclopédie méthodique haben diesem Schrifftsteller das verdiente Lobertheilt, und seine Nachrichten über die Cagots unter die medicinischen Artikel T. IV. S. 266 unter Anführung der Quelle wörtlich aufgenommen. Die Beschreibung, welche wir unsern Lesern mittheilen, ist ebenfalls aus den angeführten Quellen erborgt, und läuft bey dem Mangel umständlicherer Nachrichten in der Kürze auf folgendes hinaus.

(518) Die Bewohner der Pyrenäen erzählten Ramond mit einer Art von Beschämung: ihre Thäler enthielten eine Anzahl von Familien, welche seit undenklichen Zeiten angesehen würden, als ob sie zu einem ehrlosen und verwünschten Geschlecht gehörten. Diesen Verworfenen sey der Gebrauch der Waffen aller Orten untersagt. Ausser dem Holzspalten und Zimmern sey ihnen kein anderes Handwerk erlaubt: diese beyden Beschäftigungen seyen aber eben dadurch verächtlich und ehrlos geworden. In Bretagne, wo man sie ebenfalls seit den ältesten Zeiten, und immer unter dem ärgsten Drucke findet, haben sie sich, dem Seiler- und Fassbinder-Handwerk gewidmet. Die Verachtung und der Druck gingen in dieser Provinz so weit, dass selbst das Parlement von Rennes sich in das Mittel legen musste, um diesen Unglücklichen Begräbnisse zu verschaffen. Und die Herzoge von Bretagne haben verordnet, dass sie nie ohne ein unterscheidendes Merkinahl, einen Fleck von rothem Tuche auf ihren Kleidern, unter andern erscheinen sollen. In Navarra trugen die Priester im J. 1514 Bedenken, ihre Beichte anzuhören, und ihnen die Sacramente zu ertheilen. Der darüber entstandene Streit war so heftig, dass dieser Handel an den Papst Leo X. gebracht wurde, welcher zu ihrem Vortheil entschied. Da, wo sie als Zimmerleute dienen, sind sie verbunden, bey Feuersbrünsten an der Spritze zu arbeiten, sie müssen auch als Sclaven der Gemeinde für diese alle schimpflichen Dienste verrichten. Elend und Krankheiten aller Art, körperliche Gebrechen und vorzüglich Kröpfe sind so zu sagen ihr beschiedenes Erbtheil, auch behandelt sie der gemeine Mann als solche, welche (519) mit dem Aussatze behaftet seyen. Im eilften Jahrhundert wurden sie als Sclaven verschenkt, verkauft und in Testamenten vermacht. In Bearn unter Gaston II. schenkte ein Edelmann, welcher sich verheirathen wollte, und dazu die Einwilligung einiger Verwandten nöthing hatte, denselben unter andern Dingen auch einen Cagot.

Was sie aber den Indischen Parias sehr ähnlich macht, ist, dass sie gleich diesen mit ihren elenden Wohnungen in die Sitten sich gemildert, und die Vorurtheile nachgelassen haben, doch jede Verbindung mit diesen Unglücklichen noch immer den lebhaftesten Ekel und Abscheu erregt; dass sie in die Kirchen nicht anders, als durch abgesonderte Thüren hineintreten durften, und in diesen ihre eigenen Weihbecken und Stühle für sich und ihre Familie hatten. Diese Thüren findet man noch ein vielen Kirchen, und zu Luz findet mad die, welche zu diesem Gebrauch diente, vermauert. Sie gleichen noch ferner den Indischen Parias darin, dass dies Bearnsche Gerichtsordnung ihnen eine besondere Gnade zu beweisen glaubte, wenn sie sieben von ihren Zeugen für ein einziges Zeugniss gelten liess; dass sie im J. 1460 der Gegenstand einer Beschwerde der Bearner Landstände waren, welche verlangten, dass man ihnen wegen zu besorgender Ansteckung verbiete, mit blossen Füssen zu gehen, unter Bedrohung der Strafe, dass ihnen im Betretungsfalle die Füsse mit einem Eisen sollten durchschlagen werden. Auch drangen die Stände darauf, dass sie auf ihren Kleidern (520) ihr ehemahliges unterscheidendes Merkmahl, den Gänse - oder Aenten - Fuss fernerhin tragen sollten. *)

* ) Dass hier nicht von einer eigenen Kleidung, welche Pate d'oye heisst, sondern, wo nicht von wirklichen Gänse- und Aenten-Füssen, doch von einem Bilde derselben, welches auf dem Kleide getragen werden musste, die Rede sey, beweist folgende Stelle aus der oben angeführten Histoire de Bearn.

In Betreff dieser für den Weltweisen, so wie für den Geschichtforscher gleich merkwürdigen Menschen-Gattung entstehen nun verschiedene, zum Theil wichtige Fragen. Um das Nachdenken und den Forschungsgeist gelehrter und sachkundiger Männer zu reitzeu, werden wir einige derselben berühren. Sie verdienen eine genauere Untersuchung, und wir gestehen freymüthig, dass uns alle bisher bekannt gewordenen Auftösungen so wenig befriedigen, als wir uns selbst aus Mangel hinlänglicher Nachrichten ausser Stande sehen, etwas besseres und befriedigenderes zu geben.

Die erste und natürlichste Frage entsteht über den Namen. Woher die sonderbare Benennung Cagot? Scaliger's Meinung, welcher sie von Caas Goth, Canis Gothus ableitet, scheint ihren Gothischen Ursprung, welcher doch erst bewiesen werden sollte, als ausgemacht voraus zu setzen, auch scheint diese Ableitung zu künstlich und erzwungen zu seyn. Im Spanischen Navarra heissen die Cagots unter andern auch Agotes, ein Name, welcher wie mir jeder gestehen muss, mit Cagot die grösste Ähnlichkeit hat. Agote heisst aber in der Spanischen Sprache ein Aussätziger. Und diess ist es eben, wessen die Cagots beschuldigt, und wesswegen sie so sehr verabscheut werden. Nach einer andern Meinung führt der Bretanische Name Cacou und Caqueux näher auf die Spur. Menage leitet diese beyden Worte von cacosus und cacatus ab, und betrachtet sie als Ausdrücke, um die Verachtung zu bezeichnen, welche diese Menschen um ihres Gestanks willen erfahren. Auch Marca beruft sich in der angeführten Stelle auf das in dem Salischen Gesetze befindliche Wort Concagatus.

Es fragt sich 2) gehören die Caquets oder Caqueux in Bretagne und die Cagots in Bearn, so wie Cassos in Navarra zu einem und demselben Geschlechte? Wir glauben die Frage mit Ramond bejahen zu können. Die grosse Verwandtschaft der Namen, die Ähnlichkeit ihres Zustandes, die aller Orten gleiche Verachtung, und derselbe Geist, der aus allen Verordnungen in Betreff ihrer herverleuchtet scheinen diess zu beweisen.

Es fragt sich 3) welches ist ihr Ursprung? Diese Frage lässtsich wol am schwersten, und nicht ohne tiefe und weitläuftige Untersuchungen beantworten. Indessen hält es schwer, zu glauben, dass sie die unglucklichen Nachkommen einiger aussätzigen Familien seyn sollten. Wenn auch diese Menschen wirklich stinkend und mit ansteckenden Hautkrankheiten behastet wären, so bleibt noch die Frage zu entscheiden, ob diese diese Krankheiten nicht erst in der Folge durch Unsauberkeit, elende Lebensart und Nahrung unter ihnen herrschend geworden sind. Dazu kommt noch, dass sie seit undenklichen Zeiten nicht allein von der menschlichen Gesellschaft ausgeschlossen leben, sondern auch noch überdiess, was nie mit Aussätzigen geschehen ist, auch verschenkt und vermacht worden sind. Diess scheint auf einen kenntlichen Ursprung zu führen und lässt vermuthen, dass ihre ersten Stamm-Eltern von einen spätern Volke unterjocht wurden.

4) Welches wäre nun dasjenige Volk, welches nach seiner Unterjochung nur in diesen Elenden vorhande wäre? In keinem stücke sind die Meinungen der Schriftsteller so-sehr getheilt. Einige halten sie für die Abkömmlinge der von den Römern und späterhin von den Franken unterjochen ersten Bewohner - der Gallier. Court de Gebelin in seinem Monde primitif wählt die Alanen und führt die Schlacht vom Jahr 463 an, in welcher diese mit den Visigothen überwunden wurden. Marca betrachtet sie als Überreste der von Carl Martel unter Anführung des Abdalrahman besiegten Sarazanen. Ramond in seiner Reise nach den Pyrenäen leitet sie von den Arianisch gesinnten Völkern ab, welcher unter dem Clodoveus im Jahr 507 bey Vouglé (in Campo oder Campania Vocladensi) unter der Anführung Alarichs zehn Meilen von Poitiers geschlagen, zerstreut, misshandelt, und von den Bewohnern der Loire und der Sévre mit gleicher Erbitterung und Verachtung gegen die Mündungen dieser (523) beyden Flüsse getrieben wurden. Wer hier Recht hat, muss erst in der Folge entschieden, und ehe diess geschehen kann, die Sache noch genauer untersucht werden. Dann erst kann auch 5) die weitere Frage beantwortet werden: welches die Quelle und Veranlassung eines so weit getriebenen und zum Theil sortdauernden Hasses sey?

Es fragt sich endlich 6) welches das gegenwärtige Schicksal dieser Menschen sey? Um zu bestimmen, wie vield die Revolution und die Gleichheits - und Freyheits - Begriffe darin geändert haben; ob in einem Lande, wo der Casten-Geist so sehr bestritten wird, auch diese Spuren der gröbsten und beleidigendsten Unterscheidung vertilgt worden sind, mangeln uns gegnwärtig alle Nachrichten. Wir haben uns daher, um die Neugierde unsere Leser auch in diesem Stücke zu befriedigen, an die Quelle selbst gewendet. Wir hoffen in kurzer Zeit von Ramond selbst, welcher jetzt in den Pyrenäen lebt, die verlangten Aufschlüsse darüber zu erhalten. Wir werden nicht unterlassen, sie sogleich unsern lesern in den Correspondenz-Nachrichten mitzutheilen. Indessen bis diess geschehen kann, geben wir, was wirkönnen. Die letzten und neuesten Nachrichten schreiben sich vom J. 1787 und sind ebenfalls in Ramond's Reisen enthalten.

"Ich habe, schreibt dieser Augenzeuge, einige Familien dieser Unglücklichen gesehen. Sie nähern sich unmerklich den Dörfen aus welchen sie verbannt worden. Die Seiten-Thüren, durch welche sie in die Kirchen gingen, werden unnütz. Es vermischt sich endlich ein wenig Mitleid mit der Verachtung und dem Abscheu, welchen sie einflössen. (524) Doch habe ich auch entlegene Hütten angetrossen wo diese Unglücklichen sich 'noch fürchten, vom Vururtheile misshandelt zu werden, und nur vom Mitleiden Besuche erwarten. Ich habe daselbst vielleicht die ärmsten Geschöpfe gefunden, die es auf der Oberflache der Erde gibt, welche die Thorheit der Menschen so ungleich unter ihren Besitze vertheilt hat. Ich habe da einige Geschöpfe gesehen, welche die Gesellschaft nicht so sehr verunedeln konnte, als sie es gewollt hat. Ich habe da Brüder gefunden, die sich mit einer Zärtlichkeit lieben, die bey isolirten Menschen ein weit dringenderes Bedürfniss ist. Ich habe da Weiber gesehen, deren Liebe etwas unterwürfiges und ergebenes hatte, welches Schwachheit und Elend einflössen. Nicht ohne Entsetzen erkannte ich in der Halbvernichtung dieser Wesen meiner Art die fürchteliche Macht, welche ein Mensch über das Deseyn eines andern hat, den engen Kreis, in welchen er die Kenntnisse und das Glück seiner Brüder einschliessen, das Theilchen von Vervollkommnung, auf das er ihn einschränken kann. Ich sahe, was aus einem ganzen Menschenleben wird, wenn man es bloss auf die elenden Bemühungen, es zu erhalten, verwenden muss. Mit Grausen stiess ich den Gedanken von mir dass der Mensch in seinem ganzen Leben diesen harten Gesetzen preis gegeben werden kann."

Die Gesinnungen, welche unser Schriftsteller bey dieser Gelegenheit noch weiter aüssert machen seiner Denkungsart, noch mehr aber seinem Herzen Ehre. Wir stimmen damit ein, und würden uns glücklich schätzen, wenn dieser Aufsatz etwas (525) beytragen sollte, um das harte Loos dieser Unglücklichen zu mildern. Möchte doch Frankreich bey seiner Wiedergeburt auch diesen Flecken vertilgen, welcher in den Augen aller gesitteten Völker nicht anders als mit Abscheu betrachtet werden kann, und nirgends so sehr aüffallt, als bey einem sollchen Volke, in diesen Zeiten und unter solchen Umständen!

English

[edit]The pride of the noble and the disregard of the lower classes seems to follow all history, with the distinction of the classes of the same age, and arises from very natural causes and reasons. Since there have been wars and conquerors, there have also been servants and serfs, who at different times and by different peoples have not infrequently been treated with extraordinary severity. Even in the most perfect of all political constitutions, in the Spartan state administration, we become aware of their decrees, which upset our sense of humanity, and stand in strange contradiction with the rightly vaunted wisdom of this state. The fact that one person serves the other and is subject to the fact that the lust for power knows no boundaries should not alienate anyone. The stronger has always seized the weaker, and the government is still to be found in which all the differences between the strong and the weak disappear. This difference, and with it the suppression of the one part, will, it seems, continue for as long as there are many of unequal powers and capacities, together with one property - obstacles which cannot be easily removed. But that a people can go so far in their hatred and foresight and in their contempt against a considerable part of their fellow citizens that they do not consider these very people worthy of subjugation and servitude; that for this reason it denies them the first and most essential human rights; that this is happening even among very politicized nations - this phenomenon is so strange and striking that no one should suspect it if it is not unfortunately! That would be a fact. It is at the same time of the kind that it presents a very intricate problem for the philosopher as well as for the historian, so that resolution can adequately occupy his mind on more than one side.

We first find this geographical rarity in India. It has to be sent to our readers from Sonnerat. And to other travel writers it is very well known in what state of deepest humiliation and contempt in Hindostan the Parias, or, as those wretches on the coast of Malabar are called, the Puliats live. You find it of which the last of the Indian castes consists; from which, very well-founded assumptions, the Gypsy people, so notorious in all European countries, derive their origin.

This caste is the ejection of all others. So there is nothing like the contempt they experience. Nothing is so degrading as dealing with this class of people. The European missionaries, together with their teaching, have become a monster for the Indian. The people who make up this caste perform the lowest and most disgusting services. They bury the dead, they get rid of all excrement and rubbish; they even feed on the flesh of fallen animals. This causes them to live separately from everyone else. They are never allowed to appear among other people, and only in the greatest emergency before their master, but at all times, as is understood, at a sufficient distance, and not speak otherwise than by bringing their hand to their mouth. If a pariah has activities in a house, he cannot do anything other than enter the house through a specially designed door and with downcast eyes. If you noticed that he had taken a look into the kitchen, all the dishes on hand would have to be smashed and thrown out immediately. They are not even allowed to use the community wells. They have their own apartments close to the apartments of their masters, under the obligation that they scatter animal bones around so that everyone else will recognize and avoid them. They either live in miserable huts scattered in the fields, or at the farthest end of the city. You can, like the rest of the Indians, practice agriculture, but you can never own or lease a field. The loathing of these unfortunate people goes so far that they run the risk of losing their own life as soon as they even touch someone else. So little have even the laws provided for a life that seems too small to deserve their attention. One should believe that such an outrageous distinction would at least cease in the temples consecrated to the divinity, in those places where all people without exception appear as children of a common father and consequently as brothers, where therefore everything that reminds of distinction is rightly so should fall away. But how can we, in order to be fair, expect from the superstition of the Indians an effect which a better conviction in the minds of the Europeans has by no means brought about? Even in the temples of the European Christians, the luxury of the great and rich reminds the poor and weak only too much of their lowliness and weakness. So why is it any wonder that the Indians push their rough, undefeated prejudices even further, that they close their temples to the pariah, and that they rid them of all observance of worship customs and duties and absolve them of them? What wonder that in the opinion of the distinguished Indians there is so little a God and a church for such people as a bliss and a state?

The humiliation in which the Puliats on the coast of Malabar live is even deeper. The latter deal with the construction of hoops. Close to the fields they work there is a low hut, into which the Puliat has to flee and hide at the slightest noise of the approach of its owner. Hidden in this, he listens to his orders and orders and answers without leaving his place of refuge. This caution is the same, as often, whoever approaches his district. He even has to throw himself on his face to the earth, in case he would be surprised so quickly that he could not escape immediately. If the harvest does not correspond to the greed and greed of its owner, the owner often sets fire to his house and even fires his rifle at him when he tries to escape the flames. The way in which these degraded people are compelled to provide for their most pressing needs is no less terrible. When night fell they came to more or less numerous houses, approached the market square, and began to howl terribly at some distance. At this signal the sellers approach, and the Puliats demand what and as much they are needed. Their wishes are satisfied by placing the goods in the place where the valuable cash has been placed on their side. The love of money means that the merchant disregards all prejudices and looks at the amount without hesitation. As soon as the buyers believe that they can appear unsatisfied, they step out of their ambush and with great haste seize what they have received in this strange way.

But even these so deeply bent people - who should believe it, they too are pursuing their equals, and they think they are better than finding others out of their means. As much as even the most wretched man has as much as possible, he still needs a wretched man in order not to lose all feeling of himself! So much pursues the desire to rule over others, and the desire to present and feel something, every person in all classes, through all situations in life! These miserable people, who are a monster to all others, also find these people not free from caste pride, and cast some out of their means. These singled out, who are called Pulichis, are even forbidden to use fire. Neither are they allowed to build huts. They are therefore forced to live either in caves or on trees in the woods. Here they howl, tormented by hunger, like wild animals, to awaken the pity of those who pass by. These then bring rice or other food to the place and leave in a hurry so that the hungry can reach for it without meeting his benefactor, whom he would contaminate by his presence.

Raynal, from whose Histoire philosophique et politique etc. I drew most of this news, calls this strange phenomenon an indissoluble riddle, with the resolution of which the minds of the most keen-sighted people have hitherto occupied themselves in vain. *) He tries his own explanation, which is ingenious, but not above all doubts and objections. He believes that all pariah are originally criminals who were cast out by the rest of the cast. It depends on whether this opinion can be supported by facts from Indian history. But even in this case, since any rehabilitation is without example, this procedure would be inherited and not inherited, and no less cruel than the death penalty, in that the innocent descendants of these criminals are punished equally for the remotest generations.

But this is not the place to test that opinion. Rather, we must be amazed how it could have escaped a Raynal that similar things in Europe, even in his fatherland, happen under his eyes; that France also has its pariah. *)*) The pressure and contempt in which Jews live in most countries of Europe also seems to belong here and deserves to be reprimanded in the same way.

(Page 516) On the western coast of this country, from St. Malo to deep up the Pyrenees, there is a class of people who come very close to the Indian pariah, and are on the same level of humiliation with them. They have been scattered in these areas, from time immemorial to the present day, under constant disparagement from their more fortunate fellow citizens. With their best-known and most general designation they are called Cagots, and it remains doubtful whether the hypocrites gave them or they gave them their names, although the last one seems more credible to me. They are not only found in mountainous countries, but also in the flat areas of this empire, a fact which must not be ignored, as they differ noticeably from the Cretins or the idiots of Valais, and not, as some believe, with them these can be confused. They are known in Brittany under the name of cacous or caqueux. They can be found in Aunis, especially on the island of Maillezais, as well as in La Rochelle, where they are called Coliberts. In Guyenne and Gascogne, near Bordeaux, they appear under the name of the Cahets, and can be found in the most uninhabitable swamps, swamps and heaths. In the two Navarras they are called Caffos, Cagotes, Agotes. They are most frequently found in the valleys of Comminges, Bigorre, and Bearn, especially in the Luchoner valley. In spite of the fact that these wretches live scattered by a considerable line of France, their existence, as the example given above by Raynal shows, is completely unknown even to many French who are not from those regions. The news and testimonies from these people in books and writers are therefore extremely rare and economical. Yes, if we account for a few scattered hints that appear in public documents, all information about them can only be derived from two sources. The first and oldest source is the Histoire de Bearn par Pierre de Marca L.1. Chap / 16. What appears in Menage Dictionnaire etymologique under the article Cagot is taken literally from this source. We owe the most recent, and as one can suspect from an eyewitness, the most reliable news of 1787, to Ramond in his travels to the Pyrenees. The authors of the Encyclopédie méthodique gave this writer the praise it deserved, and verbatim included his information about the Cagots under the medical article, T. IV. P. 266, quoting the source. The description which we give our readers is also borrowed from the sources cited, and, in the absence of more detailed information, amounts in brief to the following.

(518) The inhabitants of the Pyrenees told Ramond with a sort of shame: their valleys contained a number of families who, from time immemorial, had been regarded as belonging to a dishonorable and cursed race. The use of weapons in all places is forbidden to these rejected men. Apart from splitting wood and carving, they are not allowed to do any other craft: these two occupations have become contemptible and dishonorable because of this. In Brittany, where they have also been found since the earliest times, and always under the worst pressure, they have dedicated themselves to the rope-making and cooperage craft. The contempt and pressure in this province went so far that even the Parlement of Rennes had to intervene to provide burials for these unfortunate people. And the dukes of Brittany have decreed that they should never appear among others without a distinctive mark, a stain of red cloth on their clothes. In Navarre, in 1514, the priests hesitated to hear their confessions and to give them the Sacraments. The dispute that arose over this was so violent that the deal was brought to Pope Leo X, who decided in their favor. Wherever they serve as carpenters, they are bound to work on the syringe in the event of fires; they also have to perform all shameful services as slaves of the community for all of these. Misery and illnesses of all kinds, physical ailments and especially crops are, so to speak, their inherited inheritance; the common man also treats them as those who are (519) afflicted with leprosy. In the eleventh century they were given away as slaves, sold and bequeathed in wills. In Bearn under Gaston II, a nobleman who wanted to marry and had the consent of some relatives gave them a cagot, among other things.

But what makes them very similar to the Indian pariah is that, like them, with their miserable dwellings, they have softened their morals and let up their prejudices, but every connection with these unfortunate people still arouses the most lively disgust and loathing; that they were not allowed to enter the churches other than through separate doors, and in these had their own stoups and chairs for themselves and their families. These doors can still be found in many churches, and at Luz the one which was used for this purpose is found to be walled up. They also resemble the Indian pariah in that Bearn's court order believed to show them a special grace if it allowed seven of their witnesses to count towards a single testimony; that in 1460 they were the subject of a complaint by the Bearner estates, which demanded that they should be forbidden to walk with bare feet because of contagion, under threat of the punishment that their feet should be struck with an iron in the event of trespass. The stalls also insisted that they should continue to wear (520) their former distinctive mark, the goose - or duck - foot on their clothes. *)

- ) That we are not talking about one's own clothing, which is called Pate d'oye, but, if not of real goose and duck feet, but of a picture of the same, which had to be worn on the dress, proves the following Passage from the Histoire de Bearn cited above.

With regard to this human species, which is equally remarkable for the worldly wise man as well as for the historian, various questions, some of which are important, now arise. To stimulate the thought and inquiry of learned and knowledgeable men, we shall touch on some of them. They deserve closer examination, and we frankly confess that all the resolutions hitherto known are as unsatisfactory as we find ourselves unable, for want of adequate information, to give anything better and more satisfactory.

The first and most natural question arises about the name. Where did the strange name Cagot come from? Scaliger's opinion, deriving it from Caas Goth, Canis Gothus, seems to take for granted its Gothic origin, which has yet to be proved, and this derivation seems too artificial and forced. In the Spanish Navarra the Cagots are also called Agotes, a name which everyone has to admit to me has the greatest resemblance to Cagot. Agote means a leper in Spanish. And this is just what the Cagots are blamed for and so despised for. According to another opinion, the Bretan name Cacou and Caqueux leads closer to the track. Menage derives these two words from cacosus and cacatus, and considers them expressions to denote the contempt these people experience for the sake of their stench. Marca also refers to the word Concagatus in the Salic law in the cited passage.

The question arises 2) Do the caquets or caqueux in Brittany and the cagots in Bearn, like the cassos in Navarre, belong to one and the same family? We think we can answer the question with Ramond in the affirmative. The close affinity of names, the similarity of their condition, the same contempt in all places, and the same spirit emanating from all the ordinances concerning them, seem to prove this.

The question is 3) Which is their origin? This question is perhaps the most difficult to answer, and not without deep and extensive investigation. Meanwhile it is hard to believe that they should be the unfortunate descendants of some leper families. Even if these people were really stinky and afflicted with contagious skin diseases, the question still remains to be decided whether these diseases did not first become dominant among them as a result of uncleanliness, a miserable way of life and food. What is more, from time immemorial they have not only lived excluded from human society, but moreover, what has never happened to lepers, they have also been given away and bequeathed. This seems to lead to a known origin and suggests that their first progenitors were subjugated by a later people.

4) What would that people be, which after its subjugation would be present only in these miserable ones? In no way are the opinions of the writers so divided. Some consider them to be the descendants of the first inhabitants conquered by the Romans and later by the Franks - the Gauls. Court de Gebelin in his Monde primitif chooses the Alans and cites the battle of 463, in which they were defeated with the Visigoths. Marca regards them as the remains of the Sarazans defeated by Carl Martel led by the Abdalrahman. Ramond in his Journey to the Pyrenees derives them from the Arian-minded peoples who, under the Clodoveus in the year 507 at Vouglé (in Campo or Campania Vocladensi) under the leadership of Alaric, beaten, scattered, abused ten miles from Poitiers, and treated with equal bitterness and contempt by the inhabitants of the Loire and the Sévre the mouths of (523) these two rivers were driven. Who is right here must first be decided later, and before this can happen, the matter must be examined more closely. Only then can 5) the further question be answered: What is the source and cause of a hatred that has been pushed so far and in some cases persists?

Finally, the question arises 6) What is the present destiny of these people? To determine how much the revolution and the concepts of equality - and freedom - have changed in it; Whether in a country where the spirit of casts is so much disputed even these traces of the crudest and most insulting distinction have been wiped out, we have no information at present. We have therefore turned to the source itself in order to satisfy the curiosity of our readers in this piece as well. We hope to get the information we need from Ramond himself, who now lives in the Pyrenees, in a short time. We will not fail to inform our readers in the Correspondence News. However, until that can happen, we give what we can. The latest and most recent news is dated 1787 and is also included in Ramond's Travels.

"I have seen, writes this eyewitness, some families of these unfortunates. They imperceptibly approach the villages from which they were banished. The side doors through which they went into the churches become useless. A little pity finally mixes with them the contempt and loathing they inspired. (524) Yet I have also found remote huts where these unfortunate ones still fear being mistreated by judgment, and expect visits only from pity. I have found there perhaps the poorest creatures that exist on the face of the earth, which the folly of men has divided so unequally among their possessions. I've seen some creatures that society couldn't vilify as much as it wanted. I have found brothers there who love each other with a tenderness which is a far more pressing need in isolated people. I have seen women there whose love had something submissive and devoted, which inspired weakness and misery. Not without horror did I recognize in the half-annihilation of these beings of my kind, the terrible power which a man has over the dasein (existence) of another, the narrow circle in which he includes the knowledge and happiness of his brothers, the particle of perfection upon which he can limit him. I saw what becomes of a whole human life when it has to be wasted on the miserable struggle to preserve it. I shuddered at the thought that man could be subjected to these harsh laws throughout his life."

The sentiments expressed by our writer on this occasion do more credit to his way of thinking, but still more to his heart. We concur, and would be fortunate if this paper should do (525) anything to alleviate the hard plight of these unfortunates. Would that France, when she was reborn, would also like to wipe out this stain, which in the eyes of all civilized peoples can only be looked at with disgust, and nowhere is so striking as with such a people, in these times and under such circumstances!

Grenzboten

[edit]"Die Cagots in Frankreich" [The Cagots in France]. Die Grenzboten: Zeitschrift für Politik, Literatur und Kunst (in German). Vol. 20. Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Bremen. 1861. pp. 393–398. Abgleich das geseß ihnen gegen ende des vorigen jahrhunderts gleich rechte mit den übrigen bürgern gewährte, ihre sage verbefferte und sie schüßte, ist der fluch, der aus ihnen lastete, doch noch nicht gang gehoben, die berachtung, die sie bedecste, noch nicht gang gewichen und an vielen arten wird ihre unfunft noch als ein schandflect angesehen.

Fast in allen Ländern Europa's gab es während des Mittelalters und noch weit herein in die neuere Zeit gewisse Stände, ja sogar Völferschaften, die von der übrigen Gesellschaft verachtet und gleichsam aus ihr ausgestoßen maren. Um auffallendsten war und ist dies noch bei einem Volfsstamme in Frankreich. Noch jesst gibt es in den Thälern der Pyrenäen und von Bordeaux an der Westfüste Frankreichs sich hinziehend, Ueberreste eines, die Cagots genannten, Volfsstammes. In größerer Anzahl finden sie sich in der Nieder-Bretagne. Obgleich das geseß ihnen gegen ende des vorigen jahrhunderts gleich rechte mit den übrigen bürgern gewährte, ihre sage verbefferte und sie schüßte, ist der fluch, der aus ihnen lastete, doch noch nicht gang gehoben, die berachtung, die sie bedecste, noch nicht gang gewichen und an vielen arten wird ihre unfunft noch als ein schandflect angesehen. Vor dieser Zeit hatten sie, durch grausame und harte Localgesetze gedrückt und verfolgt, Jahrhunderte lang in tiefster Verachtung von ihren, auf ihr reines Blut stolzen Nachbarn abgesondert gelebt.

Alle bestimmten Nachrichten über ihre Abtunft fehlen. Die Spuren der-selben, die schon im Mittelalter schwach und ungewiß waren, sind im Laufe der Zeit in der Art verwischt worden, daß die Abstammung der Cagots in der Gegenwart fast vollständig ein Geheimniß ist. Ebenso dunkel und räthselhaft bleiben die Gründe, weshalb sie so verachtet und von der übrigen Gesellschaft abgesondert ihr armseliges Dasein fristeten. Der Volfsausdruck nannte sie den "verfluchten Stamm". Cagots, oder Crestians, war der Name, den ihnen die übrige Gesellschaft beilegre; die Namen, die sie untereinander führten, wur-den gar nicht beachtet: sie hießen eben Cagots, gleich wie man ein Thier nur bei seinem Racenamen nent.

Ihre Häuser oder Hütten waren stets in einer gewissen Entfernung von denen der übrigen Landbewohner gelegen. Grundbesitz zu erwerben, oder Dienste zu nehmen war ihnen untersagt: es blieb ihnen daher nichts übrigen ein Handwerk zn treiben, und so waren sie denn meistens Zimmcrleute. Maurer. Dach- oder Schieferdecker. Trotzdem sie in diesen Handwerken eine ziemnliche Gefchicklicht'eit an den Tag legten, wurden ihre Dienste doch nur mit widerstreben von ihren Nachbarn in Anspruch genommen. Das geringe Weiderecht, welches sie auf dem Gemeindelande und in den Forsten besaßen, war noch durch strenge, auf die Zahl ihres Vichstandes sich beziehende Gesetze sehr beschränkt. Durch eine Verordnung war es ihnen verboten mehr als 20 Schafe, ein Schwein, einen Widder und sechs Ziegen zu halten. Das Schwein sollte als Nahrung für den Winter dienen, die Wolle der Schafe ihnen Kleidung gewähren. Einen andern Nutzen von den Schafen hatten sie nicht, denn die Lämmer, die sie von ihnen erhielten, zu essen war ihnen gleichfalls untersagt. Die einzige Vergünstigung, die sie genossen, bestand darin, daß sie von ihren Lämmern anstatt der alten Schafe die besten zur Zucht auslesen durften. Um die Befolgung dieser Verordnung zu conttoliren, gingen zu Martini jedes Jahres die Ortsbehörden herum und überzählten den Viehstand eines jeden Cagots. Besaß er mehr als die bestimmte Anzahl, so wurden ihm die überzähligen Thiere weggenommen. Die eine Hälfte erhielt die Gemeinde, die andere der Gemeindevorsteher. Doch nicht auf die Menschen allein, auch auf die Thiere erstreckte sich dieser Druck und diese Beschränkung. Während die Heerden der Dorfbewohner die Gemeinde-weiden unbeschränkt benutzen und sich das Beste auswählen konnten, war den Thieren der Cagots nur ein beschränkter, jedoch durch keine Einfriedigung abgeschlossener. Raum zur Weide angewiesen. Ueberschntt nun eins ihrer Thiere die Grenzlinie, so war jedermann berechtigt es zu todten. Von dem Fleische erhielt dann der Eigenthümer nur einen geringen Theil. Der Schaden, den ein Cagotsschaf angerichtet, ward abgeschätzt und war von seinem Herrn zu tragen.

In Städten durften sie nie ihre Wohnung haben. Strenge Gesetze geboten jedem Cagot, der fast nur seines Gewerbes wegen die Stadt betrat, allen Begegnenden gehörig auszuweichen. Durch jede Verordnung wurden sie an ihre armselige Lage erinnert. In allen Städten des Distrikts, den sie diesseits und jenseits der Pyrenäen. — in den sranzösischen und spanischen Theilen — bewohnten, war es ihnen untersagt etwas Eßbares zu kaufen oder zu verkaufen; ebenso durften sie nicht in der Mitte der Straßen gehen. Vor Sonnenaufgang eine Stadt zu betreten, sowie nach Sonnenuntergang sich noch in deren Mauern aufzuhalten, war ihnen ebenfalls nicht gestattet. Obschon allerdings die Cagots von Natur gewisse Kennzeichen ihrer Abkunft an sich trugen, so wurden sie doch, um sie jedem Begegnenden sofort kenntlich zu machen, gezwungen, auch gewisse auffallende Kennzeichen an ihrer Kleidung zu tragen. In den meisten Städten war daher die Bestimmung getroffen worden, daß jeder Cagot aus der vorderen Seite seines Kleides ein Stück rothen Zeuges tragen sollte; in anderen Städten bestand dieses Zeichen in einer Eierschaale oder einem Enten-resp. Gänsefuße über der linken Schulter. Statt dessen wählte man später ein in Gestalt eineö Entenfußes ausgeschnittenes Stück gelben Tuches. Ward ein Cagot m Stadt oder Dorf ohne Zeichen angetroffen, so hatte er eine Strafe von etwa 5 Sou's zu erlegen und verlor seine Kleider. Es ist wahrhaft empörend, wie weit die Grausamkeit und Bedrückung gegen diesen bemitleidenswcrthen Stamm ging. Arbeitete ein Cagot in einer Stadt, so hatte er kein Mitlei seinen Durst zu stillen; denn sowol der Besuch der öffentlichen Schenkhäuser, als auck das Wasserschöpfen aus den Brunnen der Stadt war ihm untersagt. Nur aus dem in ihrem schmutzigen Dorfe befindlichen Brunnen durften sie trinken. Kam ein Cagotweib an einem andern als dem Montage in die Stadt, um Einkäufe zu besorgen, so sehte sie sich der Gefahr aus hinausgepeitscht zu werden.

Weit strenger als irgendwo trat das Vorurtheil, und eine Zeit lang auch die Gesetze im Baskenlande gegen die Cagots auf. Schafe durste der baskische Cagot nicht halten, ein Schwein war ihm gestaltet; doch hatte dasselbe kein Weiderecht. Für den Esel, das einzige Thier, dessen Besitz ihm noch erlaubt war, durfte er etwas Gras abmähen; doch war dieser Esel für den Unterdrücker eher als für den Unterdrückten von Nutzen, da jener ihn als bequemes Transportmittel fortwährend in Anspruch nahm.

Der Staat stieß sie von sich. Auch nicht einmal den geringsten öffentlichen Posten konnten sie bekleiden. Von der Kirche wurden sie kaum geduldet, obschon sie gute Katholiken und eifrige Besucher der Messe waren. Die Kirchen durften sie nur durch schmale und sehr niedrige, besonders für sie hergerichtete Thüren betreten, durch die nie ein anderer Mensch ging. In der Kirche selbst hatten sie von den übrigen Leuten entfernt ihren bestimmten Platz in der Nähe der Thüre. Ebenso hatten sie ihr eigenes Weihwasser. Vom Genuß des heiligen Abendmahls waren sie ausgeschlossen. Nur in einigen toleranteren Pyrenäendörfern ward den Cagots vom Priester auf einer langen hölzernen Gabel ans einer gewissen Entfernung das geweihte Brod dargereicht. Starb ein Cagot, so ward er auf einem an der Nordseite des Kirchhofs gelegenen Vegräbnißplatze beerdigt. Doch nicht genug, daß er bei Lebzeiten durch harte Verordnungen und Bestimmungen so gedrückt wurde, daß er nicht im Stande war seinen Kindern viel Vermögen zu hinterlassen: noch im Tode hörte der Druck nicht auf. denn gewisse Theile der Hinterlassenschaft waren der Gemeinde verfallen, ähnlich wie in Deutschland das s. g. Sterbelehen, oder der Sterbefall in dienender Hand.

Bei einer so grausamen Behandlung muß es uns ganz natürlich erscheinen, wenn dieses gequälte Volk zu Zeiten sich gegen seine Unterdrücker erhob und blutig den Frevel rächte, den man an ihnen verübte. So erhoben sich z. B, zu Anfang des vorigen Jahrhunderts in dem Departement der Hochpyrenäen die Cagots von Rehouilhes gegen die Einwohner der benachbarten Stadt Lourdes. Durch Zauberkünste hatten sie, wie man behauptete, den angeseheneren Theil der Einwohner für sich gewonnen, und so gelang es ihnen, das Volk von Lourdes zu besiegen. Die blutigen Köpfe der Erschlagenen dienten den Cagots als Kegelkugeln. Die Behörden, sei es, daß sie durch eine harte Bestrafung den gemißhandelten Stamm noch mehr aufzureizen fürchteten, sei es, daß sie aus Menschlichkeit die Schwere des auf den Unglücklichen lastenden Fluches nickt noch vermeinen wollten, waren der Meinung, dies Vergeben nicht zu hart bestrafen zu dürfen. Der Gerichtshof von Toulouse verurtheilte daher nur die bei dem Aufstande besonders gravirten Cagotsanführer zum Tode, verordnete aber, noch immer hart genug, daß von nun an die Cagots nur durch ein gewisses, Cagot-Pourtet genanntes, Thor die Stadt Lourdcs betreten, stets unter den Dachrinnen weggehen und in der Stadt sich weder niedersetzen, noch essen oder trinken durften. Durch den furzen Aufenthalt in jeuer Stadt also, den ihnen diese Verordnung gestattete, sollte jedes Zusammenkommen der Cagots mit den Einwohnern möglichst vermieden werden. Verstieß ein Cagot gegen eine dieser Bestimmungen, so sollten ihm zwei Stücken Fleisch, jedes nicht über zwei Unzen schwer, auf beiden Seiten des Rückens ausgeschnitten werden.

Im vierzehnten, fünfzehnten und sechzehnten Jahrhundert galt es für lein größeres Verbrechen einen Cagot zu tödten, als irgend ein schädliches Thier zu vertilgen. So wird berichtet, daß sich etwa um's Jahr 1600 in dem alten Schlosse in der Nähe der Stadt Maurefin, Departement Gers, „ein Cagotnest" gebildet habe. Ihren Ruf als Zauberer benutzten sie zur Beunruhigung ihrer Nachbarn und zu ihrem eigenen Vortheil. Durch allen nur möglichen Spuk setzten sie die Bewohner der Gegend in Schrecken, und ärgerten sie noch dadurch, daß sie beharrlich aus deren Brunnen Wasser schöpften. Da zu diesen Quälereien auch noch mancherlei kleine Diebstähle kamen, die in der Umgegend fortwährend verübt wurden, so hielten sich die Einwohner der umliegenden Städte und Dörfer für vollkommen berechtigt, dieses Nest zu zerstören. Allein das Schloß war mit einem tiefen Wassergraben umgeben, über den als einziger Zugang eine Zugbrücke führte, und die Cagots waren sehr auf ihrer Hut. Durch folgende List jedoch gelangte man zum Zwecke. Ein Mann legte sich auf dem nach dem Schlosse führenden Wege der Cagots nieder und stellte sich todtkrank. Die Cagots fänden ihn, nahmen ihn mit sich in ihre Festung und glaubten durch seine Wiederherstellung ihn sich zum Freunde gemacht zu haben. Eines Tages aber, als sie sämmtlich im Walde mit Kegelspielen sich vergnügten, verlieh ihr verrätherischer Freund, großen Durst vorschützend, die Gesellschaft und eilte nach dem Schlosse zurück. Dort angekommen, zog er die Brücke, nachdem er sie passirt, auf, den Weg zur Rettung aus diese Weise ihnen abschneidend. Hieraus begab er sich auf den höchsten Punkt des Schlosses und gab seinen aus der Lauer liegenden Freunden durch einen Hornruf das verabredete Zeicken, auf welches diese über die in ihr Spiel vertieften, nichts Böses ahnenden Cagots herfielen und sie sämmtlich erschlugen. Die Thäter erlitten keinerlei Strafe.

Wie bei den Germanen jede Heirath zwischen Freien und Unfreien, so war den Cagots jede Verbindung mit der reinen Race auf‘s Strengste untersagt. Da nun außerdem noch in jeder Gemeinde Listen über Namen und Wohnung der einzelnen Cagots geführt wurden, so hatte dies unglückliche Volk keine Aussicht sich mit der übrigen Bevölkerung vermischen zu können. Fand eine Eagothoehzeit statt, so ward das junge Paar durch allerlei Spottgedichte verhöhnt. Aber obgleich es auch unter den Cagots Dichter gab, deren Romanzen noch jetzt in der Bretagne im Munde Vieler leben, so versuchten sie doch nie Gleiches mit Gleichem zu vergelten. Eine liebreiche Sinnesart und ein gewisses poetisches Talent waren ihnen eigen, und nur diese Eigenschaften, in Verbindung mit ihrer Geschicklichkeit in mechanischen Arbeiten, konnten ihnen ihr trauriges Loos einigermaßen erträglich machen.

Um ihre Lage in irgend etwas zu erleichtern, thaten sie einen Schritt, der leider die gehoffte Wirkung verfehlte. Sie wandten sich nämlich mit der Bitte um Schutz durch die Gesetze an die Behörden und erlangten diesen auch gegen Ende des siebzehnten Jahrhunderts. Doch der einmal so tief eingewurzelte Widerwille war mächtiger als das Gesetz, und dieses hatte nur zur Folge, daß sich jener Abscheu immer mehr steigerte und nach und nach bis zum wüthendsten Hasse heranwuchs. Zu Anfang des sechzehnten Jahrhunderts beschwerten sieb die Cagots von Navarra beim Papste: daß sie von der menschlichen Gesellschaft ausgestoßen und von der Kirche verflucht seien, aus dem einzigen Grunde, weil ihre Vorfahren einem gewissen Grafen Robert von Toulouse in seiner Empörung gegen den heiligen Stuhl Beistand geleistet, und baten den heiligen Vater die Sünden der Väter nicht auf sie überzutragen. In einer Bulle vom 13. Mai 1515 bestimmte dieser, daß sie gut behandelt und ihnen dieselben Vorrechte wie dem übrigen Volke eingeräumt werden sollten. Die Ausführung dieser Bulle übertrug er dem Bischof Don Juan de Santa Maria von Pampeluna, der sich jedoch damit nicht allzusehr beeilte. Ungeduldig über eine so lange Verzögerung beschlossen die Cagots bei einer weltlichenMacht Hilfe zu suchen, und wandten sich demgemäß Cagots bei einer weltlichenMacht Hilfe zu suchen, und wandten sich demgemäß mit ihrer Bitte an die Cortes von Navarra. Sie wurden abschläglich beschicken. Die famosen Argumente dieses Beschlusses wären folgende: die Borfahren der Cagots hätten nie etwas mit Robert, Grasen von Toulouse, oder einer dergleichen ritterlichen Person zu thun gehabt; dagegen seien sie in Wirklichkeit Nachkommen Gehasi's, des Propheten Elisa Dieners, der von seinem Herrn, wegen seines Betrugs an dem syrischen Feldhauptmann Naemann, verflucht und mit seiner ganzen Nachkommenschaft für ewig mit dein Aussatze belegt worden sei (II. Buch der Könige. Cap. 5). Daher rühre auch der Name, denn Cagots sei entstanden aus, Gahets, Gahets aus Gehasites. Behaupte aber Jemand, - das die Cagots jetzt nicht mehr mit dem Aussatze behaftet seien, so müsse man erwidern, daß es zwei Arten des Aussatzes gebe, die eine sichtbar, die andere aber nicht ein mal denen, die daran leiden bemerklich. Außerdem heiße es ja auch allgemein, daß da, wo ein Cagot seinen Fuß hinsetze, das Gras verwelke, ein Umstand, der doch unzweifelhaft die unnatürliche und krankhafte Hitze des Körpers bekunde. Ebenso könnten glaubwürdige und zuverlässige Leute beweisen, daß ein Apfel, den ein Cagot in der Hand gehalten, binnen kurzer Zeit ganz zusammenschrumpfe, als sei er verdorrt oder erfroren. Noch entsetzlicher sei es aber, daß sie mit Schwänzen zur Welt kämen; es sei dies Wohl bekannt, obgleich die Eltern dieselben sofort nach der Geburt abschnitten. Wäre dies nicht der Fall, weshalb sollten sich denn da die Kinder der reinen Race damit ergötzen, den in ihre Arbeit vertieften Cagots Schwänze von Schaafen an ihre Kleider zu heften? Dazu komme noch, daß der Geruch, den sie verbreiteten, so unerträglich sei, daß sie ganz natürlich die ärgsten Ketzer sein müßten, denn von dem Wohlgeruche der Heiligkeit und dem Weibrauche der guten Arbeiter spreche Jedermann." Glänzende Beweise! die aber leider zur Folge hatte, daß die Stellung jener armen Menschen eine noch weit schlechtere wurde, als bisher.

Der Papst beharrte bei seiner Bestimmung, daß die Cagots alle Rechte und Privilegien der übrigen Christen genießen sollten, doch stillschweigend verweigerten die spanischen Priester den Cagots diese Gleichstellung. Weder im Leben, noch im Tode durften sie sich mit andern Menschen vermischen. Ebenso erging es den Verordnungen, die Kaiser Karl der Fünfte zu ihren Gunsten erließ: niemand befolgte sie; ja sie bewirkten sogar das Gegentheil von dem, was sie bezweckten. Aus Rache nämlich und zur Strafe für die unerhörte Frechheit, sich über ihre noch zu milde Behandlung beschwert zu haben, nahmen ihnen die Ortsbehörden sämmtliches Werkzeug weg, so daß viele von ihnen Hungers starben; so verhungerte unter Andern ein alter Mann mitsammt seiner Familie, da er nickt mehr fischen konnte.

(Schluß in nächster Nummer).

In almost all European countries during the Middle Ages and well into modern times there were certain classes, even groups of people, who were despised by the rest of society and, as it were, expelled from it. This was and is still the most conspicuous among a folk tribe in France. Still now there are in the valleys of the Pyrenees and Bordeaux on the western coast of France the remains of a folk tribe called the Cagots. They can be found in large numbers in Lower Brittany. Although towards the end of the last century the law granted them rights equal to those of the rest of the citizens, enhanced their sayings and shot them, the curse that weighed on them has not yet been lifted, the observation that covered them has not yet given way and in many species their injustice is still seen as a blot on them. Before that time, forced and persecuted by cruel and harsh local laws, they had lived for centuries in deep contempt from their neighbours, who were proud of their pure blood.

All certain news about their abortion are missing. The traces of the same, which were already weak and uncertain in the Middle Ages, have been erased in the course of time in such a way that the ancestry of the Cagots is almost entirely a mystery in the present. The reasons why they were so despised and separated from the rest of society remain just as obscure and enigmatic as their miserable existence. The folk expression called them the "accursed tribe". Cagots, or Crestians, was the name given to them by the rest of society; the names which they led among one another were ignored: they were called Cagots, just as an animal is only called by its race name.

Their houses or huts were always located at a certain distance from those of the other rural residents. They were forbidden from acquiring property or taking on services; they therefore had no choice but to practice a trade, and so they were mostly carpenters. Bricklayer. Roofers or slaters. Although they displayed considerable skill in these trades, their services were only reluctantly used by their neighbours. The limited grazing rights they had on communal land and in the forests were still very limited by strict laws relating to the number of their livestock. A regulation prohibited them from keeping more than 20 sheep, one pig, one ram and six goats. The pig was supposed to serve as food for the winter, and the wool from the sheep was supposed to provide them with clothing. They had no other benefit from the sheep, because they were also forbidden to eat the lambs that they received from them. The only advantage they enjoyed was that they were allowed to select the best of their lambs for breeding instead of the old sheep. In order to monitor compliance with this regulation, at Martini every year the local authorities went around and counted the number of livestock in each cagot. If he had more than the specified number, the surplus animals were taken away from him. The community received one half and the community leader received the other half. But this pressure and restriction did not only apply to people, but also to animals. While the villagers' herds had unlimited use of the communal pastures and could choose the best for themselves, the Cagots' animals had only limited use, but no enclosure. Space allocated for pasture. If one of their animals crossed the border line, anyone was entitled to kill it. The owner then received only a small portion of the meat. The damage caused by a Cagot sheep was assessed and had to be borne by its master.

Avoid encountering enemies properly. Every decree reminded them of their miserable situation. In all the towns of the district on both sides of the Pyrenees. - in the French and Spanish parts - they were forbidden to buy or sell anything edible; likewise, they were not allowed to walk in the middle of the streets. They were also not allowed to enter a city before sunrise or to remain within its walls after sunset.

Although the Cagots naturally bore certain marks of their descent, in order to make them immediately recognizable to anyone they met, they were forced to wear certain conspicuous marks on their clothing. In most cities, therefore, it was decreed that every Cagot should wear a piece of red cloth from the front of his dress; in other cities this symbol consisted of an eggshell or a duck. Goose feet over the left shoulder. Instead, a piece of yellow cloth cut out in the shape of a duck's foot was later chosen. If a cagot was found in a town or village without a sign, he had to pay a fine of about 5 sou's and lost his clothes It is truly outrageous how far the cruelty and oppression went against this pitiful tribe. If a Cagot worked in a city, he had no compassion to quench his thirst; because he was forbidden from visiting public taverns or drawing water from the city's wells. They were only allowed to drink from the well in their dirty village. If a Cagot woman came into town to do some shopping on a day other than Monday, she was in danger of being whipped out.

The prejudice and, for a time, the laws in the Basque Country were far more severe against the Cagots than anywhere else. The Basque Cagot did not want to keep sheep; a pig was designed for him; but it had no grazing rights. He was allowed to cut some grass for the donkey, the only animal he was still allowed to own; but this donkey was more useful to the oppressor than to the oppressed, since he continually used it as a convenient means of transportation.

The state pushed them away. They couldn't even hold the lowest public position. They were hardly tolerated by the church, even though they were good Catholics and eager mass attendees. They were only allowed to enter the churches through narrow and very low doors that were specially prepared for them and through which no other person ever went. In the church itself they had their designated place near the door, away from the rest of the people. They also had their own holy water. They were excluded from enjoying Holy Communion. Only in some more tolerant Pyrenean villages was the consecrated bread presented to the Cagots by the priest on a long wooden fork at a certain distance. If a Cagot died, he was buried in a burial place on the north side of the churchyard. But it was not enough that during his lifetime he was so oppressed by harsh regulations and regulations that he was unable to leave much wealth to his children: the pressure did not stop even in death. because certain parts of the legacy were forfeited to the community, similar to the so-called dying fief in Germany, or death in serving hands.

Given such cruel treatment, it must seem quite natural to us that this tormented people should at times rise up against their oppressors and take bloody revenge for the outrage committed against them. For example, At the beginning of the last century in the department of the High Pyrenees the Cagots of Rehouilhes fought against the inhabitants of the neighbouring city of Lourdes. [-Also mentioned in Gaskell’s An Accursed Race-] It was said that they had won over the more respected part of the inhabitants through magical arts, and so they succeeded in defeating the people of Lourdes. The Cagots used the bloody heads of the slain as bowling balls. The authorities, either because they feared that a harsh punishment would provoke the mistreated tribe even further, or because they wanted to avoid the seriousness of the curse placed on the unfortunate people out of humanity, were of the opinion that this forgiveness should not be punished too harshly to be allowed. The court of Toulouse therefore sentenced to death only the Cagot leaders who were particularly engraved in the uprising, but decreed, still harshly enough, that from now on the Cagots should only enter the city of Lourds through a certain gate called Cagot-Pourtet, always among the gutters and were not allowed to sit down, eat or drink in the city. By staying in your city, which this regulation allowed them, any meeting between the Cagots and the residents was to be avoided as far as possible. If a cagot violated any of these regulations, two pieces of meat, each not exceeding two ounces in weight, should be cut from either side of its back.

In the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries it was considered a greater crime to kill a cagot than to destroy any harmful animal. It is reported that around the year 1600 a "cagot nest" was formed in the old castle near the town of Maurefin, Gers department. They used their reputation as magicians to alarm their neighbours and for their own benefit Because of possible ghosts, they frightened the residents of the area and further annoyed them by persistently drawing water from their wells. Since these torments were also accompanied by various small thefts that were constantly being committed in the area, the residents held their ground of the surrounding towns and villages were completely justified in destroying this nest. But the castle was surrounded by a deep moat, over which the only access was a drawbridge, and the Cagots were very on their guard. However, the following trick achieved their purpose A man lay down on the Cagots' path leading to the castle and pretended to be deathly ill. The Cagots found him, took him with them to their fortress and believed that by restoring him they had made a friend of him. But one day, while they were all having fun playing bowling in the forest, their treacherous friend, pretending to be very thirsty, left the company and hurried back to the castle. Once there, he opened the bridge after he had passed it, thereby cutting off their path to rescue. From here he went to the highest point of the castle and gave his friends, who were lying in wait, the agreed signal by calling the horn, at which they attacked the Cagots, who were engrossed in their game and suspected no harm, and killed them all. The perpetrators suffered no punishment.

As with the Germanic tribes, any marriage between free and unfree people was strictly forbidden for the Cagots to have any connection with the pure race. Since lists of the names and residences of the individual Cagots were kept in every community, this unfortunate people had no chance of being able to mix with the rest of the population. If a marriage ceremony took place, the young couple was mocked by all sorts of mocking poems. But although there were poets among the Cagots whose romances still live in the mouths of many in Brittany, they never tried to repay like for like. They had a loving disposition and a certain poetic talent, and only these qualities, combined with their skill in mechanical work, could make their sad situation somewhat bearable.

In order to ease their situation in some way, they took a step that unfortunately failed to have the desired effect. They turned to the authorities for protection under the law and obtained this towards the end of the seventeenth century. But the revulsion, once so deeply rooted, was more powerful than the law, and this only resulted in the revulsion increasing and gradually growing into the most raging hatred. At the beginning of the sixteenth century, seven of the Cagots of Navarre complained to the Pope that they were outcasts from human society and cursed by the Church, for the sole reason that their ancestors had assisted a certain Count Robert of Toulouse in his rebellion against the Holy See accomplished, and asked the Holy Father not to pass on the sins of the fathers to them. In a bull of May 13, 1515, he determined that they should be treated well and given the same privileges as the rest of the people. He entrusted the execution of this bull to Bishop Don Juan de Santa Maria of Pampeluna, who, however, did not hurry with it. Impatient at so long a delay, the Cagots decided to seek help from a secular power, and accordingly turned to the Cortes of Navarre for help from a secular power. They were rejected. The famous arguments for this decision would be as follows: the Cagots' borrowings never had anything to do with Robert, Grassen of Toulouse, or any such chivalrous personage; On the other hand, they are actually descendants of Gehazi, the prophet Elisha's servant, who was cursed by his master because of his betrayal of the Syrian captain Naeman and who, along with his entire offspring, was subjected to leprosy forever (II. Book of Kings. Cap. 5). This is where the name comes from, because Cagots came into being from, Gahets, Gahets from Gehazites. But if someone claims that the Cagots are no longer afflicted with leprosy, one must reply that there are two types of leprosy, one visible, the other not even noticeable to those who suffer from it. Furthermore, it is also generally said that wherever a cagot puts his foot, the grass withers, a circumstance that undoubtedly shows the unnatural and pathological heat of the body. In the same way, credible and reliable people could prove that an apple held in a cagot's hand would shrink completely within a short time, as if it had withered or frozen. But it is even more horrifying that they are born with tails; This is well known, although the parents cut them off immediately after birth. If this were not the case, why should the children of the pure race amuse themselves by pinning sheep's tails to the clothes of the Cagots, who are absorbed in their work? In addition, the smell that they spread was so unbearable that they would naturally have to be the worst heretics, because everyone speaks of the scent of holiness and the incense of good workers." Brilliant proof! but unfortunately that results that the position of those poor people became even worse than before.

The Pope insisted that the Cagots should enjoy all the rights and privileges of other Christians, but the Spanish priests silently denied the Cagots this equality. Neither in life nor in death were they allowed to mix with other people. The same thing happened to the decrees that Emperor Charles the Fifth issued in their favour: no one followed them; yes, they even had the opposite effect of what they were intended to do. In revenge and as punishment for their outrageous impudence in complaining about their too lenient treatment, the local authorities took away all their tools, so that many of them died of hunger; Among others, an old man and his family starved to death because he could no longer fish.

(End in next number).

[Die Cagots in Frankreich.

(Schluß des Artikels in voriger Nummer).