User:Phlsph7/Mind - Non-human

Non-human

[edit]Animal

[edit]While it is generally accepted today that animals have some form of mind, it is controversial to which animals this applies and how their mind differs from the human mind.[1] Different conceptions of the mind lead to different responses to this problem; when understood in a very wide sense as the capacity to process information, the mind is present in all forms of life, including insects, plants, and individual cells;[2] on the other side of the spectrum are views that deny the existence of mentality in most or all non-human animals based on the idea that they lack key mental capacities, like abstract rationality and symbolic language.[3] The status of animal minds is highly relevant to the field of ethics since it affects the treatment of animals, including the topic of animal rights.[4]

Discontinuity views state that the minds of non-human animals are fundamentally different from human minds and often point to higher mental faculties, like thinking, reasoning, and decision-making based on beliefs and desires.[5] This outlook is reflected in the traditionally influential position of defining humans as "rational animals" as opposed to all other animals.[6] Continuity views, by contrast, emphasize similarities and see the increased human mental capacities as a matter of degree rather than kind. Central considerations for this position are the shared evolutionary origin, organic similarities on the level of brain and nervous system, and observable behavior, ranging from problem-solving skills, animal communication, and reactions to and expressions of pain and pleasure. Of particular importance are the questions of consciousness and sentience, that is, to what extent non-human animals have a subjective experience of the world and are capable of suffering and feeling joy.[7]

Artificial

[edit]

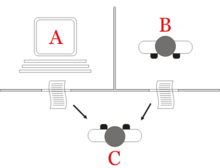

Some of the difficulties of assessing animal minds are also reflected in the topic of artificial minds, that is, the question of whether computer systems implementing artificial intelligence should be considered a form of mind.[8] This idea is consistent with some theories of the nature of mind, such as functionalism and its idea that mental concepts describe functional roles, which are implemented by biological brains but could in principle also be implemented by artificial devices.[9] The Turing test is a traditionally influential procedure to test artificial intelligence: a person exchanges messages with two parties, one of them a human and the other a computer. The computer passes the test if it is not possible to reliably tell which party is the human and which one is the computer. While there are computer programs today that may pass the Turing test, this alone is usually not accepted as conclusive proof of mindedness.[10] For other aspects of mind, it is more controversial whether computers can, in principle, implement them, such as desires, feelings, consciousness, and free will.[11]

This problem is often discussed through the contrast between weak and strong artificial intelligence. Weak or narrow artificial intelligence is limited to specific mental capacities or functions. It focuses on a particular task or a narrow set of tasks, like automatic driving, speech recognition, or theorem proving. The goal of strong AI, also termed artificial general intelligence, is to create a complete artificial person that has all the mental capacities of humans, including consciousness, emotion, and reason.[12] It is controversial whether strong AI is possible; influential arguments against it include John Searle's Chinese Room Argument and Hubert Dreyfus's critique based on Heideggerian philosophy.[13]

Sources

[edit]- Franklin, Stan (1995). Artificial minds. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-06178-3.

- Fjelland, Ragnar (2020). "Why General Artificial Intelligence Will Not be Realized". Humanities and Social Sciences Communications. 7 (1). doi:10.1057/s41599-020-0494-4. ISSN 2662-9992.

- Butz, Martin V. (2021). "Towards Strong AI". KI - Künstliche Intelligenz. 35 (1). doi:10.1007/s13218-021-00705-x.

- Chen, Zhaoman (2023). "Exploration of Youth Social Work Model Driven by Artificial Intelligence". In Hung, Jason C.; Yen, Neil Y.; Chang, Jia-Wei (eds.). Frontier Computing: Theory, Technologies and Applications (FC 2022). Springer Nature. ISBN 978-981-99-1428-9.

- Biever, Celeste (2023). "ChatGPT broke the Turing test — the race is on for new ways to assess AI". Nature. 619 (7971). doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02361-7.

- Bringsjord, Selmer; Govindarajulu, Naveen Sundar (2024). "Artificial Intelligence". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- Carruthers, Peter (2004). The Nature of the Mind: An Introduction (1 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-29994-2.

- Anderson, Neal G.; Piccinini, Gualtiero (2024). The Physical Signature of Computation: A Robust Mapping Account. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-883364-2.

- McClelland, Tom (2021). What is Philosophy of Mind?. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-5095-3878-2.

- Penn, Derek C.; Holyoak, Keith J.; Povinelli, Daniel J. (2008). "Darwin's Mistake: Explaining the Discontinuity between Human and Nonhuman Minds". Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 31 (2). doi:10.1017/S0140525X08003543.

- Melis, Giacomo; Monsó, Susana (2023). "Are Humans the Only Rational Animals?". The Philosophical Quarterly. doi:10.1093/pq/pqad090.

- Rysiew, Patrick (2012). "Rationality". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- Griffin, Donald R. (1998). "Mind, Animal". States of Brain and Mind. Springer Science. ISBN 978-1-4899-6773-2.

- Fischer, Bob (2021). Animal Ethics: A Contemporary Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-48440-5.

- Thomas, Evan (2020). "Descartes on the Animal Within, and the Animals Without". Canadian Journal of Philosophy. 50 (8). doi:10.1017/can.2020.44. ISSN 0045-5091.

- Steiner, Gary (2014). "Cognition and Community". In Petrus, Klaus; Wild, Markus (eds.). Animal Minds & Animal Ethics: Connecting Two Separate Fields. transcript Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8394-2462-9.

- Lurz, Robert. "Minds, Animal". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- Carruthers, Peter (2019). Human and animal minds: the consciousness questions laid to rest (1 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-884370-2.

- Spradlin, W. W.; Porterfield, P. B. (2012). The Search for Certainty. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4612-5212-2.

- Griffin, Donald R. (2013). Animal Minds: Beyond Cognition to Consciousness. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-22712-2.

- ^

- Carruthers 2019, pp. ix, 29–30

- Griffin 1998, pp. 53–55

- ^ Spradlin & Porterfield 2012, pp. 17–18

- ^

- Carruthers 2019, pp. 29–30

- Steiner 2014, p. 93

- Thomas 2020, pp. 999–1000

- ^

- Griffin 2013, p. ix

- Carruthers 2019, p. ix

- Fischer 2021, pp. 28–29

- ^

- Fischer 2021, pp. 30–32

- Lurz, Lead Section

- Carruthers 2019, pp. ix, 29–30

- Penn, Holyoak & Povinelli 2008, pp. 109–110

- ^

- Melis & Monsó 2023, pp. 1–2

- Rysiew 2012

- ^

- Fischer 2021, pp. 32–35

- Lurz, Lead Section

- Griffin 1998, pp. 53–55

- Carruthers 2019, pp. ix–x

- Penn, Holyoak & Povinelli 2008, pp. 109–110

- ^

- McClelland 2021, p. 81

- Franklin 1995, pp. 1–2

- Anderson & Piccinini 2024, pp. 232–233

- Carruthers 2004, pp. 267–268

- ^

- Carruthers 2004, pp. 267–268

- Levin 2023, Lead Section, § 1. What is Functionalism?

- Searle 2004, p. 62

- Jaworski 2011, pp. 136–137

- ^

- Biever 2023, pp. 686–689

- Carruthers 2004, pp. 248–249, 269–270

- ^ Carruthers 2004, pp. 270–273

- ^

- Chen 2023, p. 1141

- Bringsjord & Govindarajulu 2024, § 8. Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence

- Butz 2021, pp. 91–92

- ^

- Bringsjord & Govindarajulu 2024, § 8. Philosophy of Artificial Intelligence

- Fjelland 2020, pp. 1–2