West Nile campaign (October 1980)

| West Nile campaign | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ugandan Bush War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Armed Madi civilians |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Elly Aseni † | Ojul[1] | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Several groups |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

c. 7,100 (total Uganda Army)

|

Unknown UNLA Thousands of militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Low | 200+ killed | ||||||

| 1,000–30,000 civilians killed, 250,000 displaced | |||||||

In October 1980, Uganda's West Nile Region was the site of a major military campaign, as Uganda Army (UA) remnants invaded from Zaire as well as Sudan and seized several major settlements, followed by a counteroffensive by the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA) supported by militias and Tanzanian forces. The campaign resulted in large-scale destruction and massacres of civilians, mostly perpetrated by the UNLA and allied militants, with 1,000 to 30,000 civilians killed and 250,000 displaced. The clashes mark the beginning of the Ugandan Bush War.

Background

[edit]

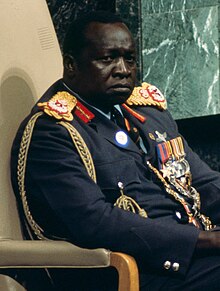

In 1971, Ugandan President Milton Obote was overthrown in a military coup. He was succeeded by Idi Amin who established a repressive military dictatorship. Ethnic groups perceived as supportive of Obote, most importantly the Acholi and Langi, were subjected to suppression and violence by the new regime; Acholi and Langi soldiers in the Uganda Army (UA) were purged and massacred. In turn, Amin empowered natives of the West Nile Region, furthering existing ethnic tensions. Obote and other opposition members went into exile, from where they attempted to organize rebel groups. Amin was ultimately overthrown by Tanzania and the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA), a rebel coalition, during the Uganda–Tanzania War of 1978–79.[2] After the Fall of Kampala, Uganda's capital, a new government led by President Yusuf Lule was formed by the Uganda National Liberation Front (UNLF) and the Tanzanians.[3][4] Many Amin loyalists and Uganda Army soldiers fled to the West Nile Region which became the last part of Uganda to remain outside Tanzanian-UNLA control.[5]

When the Tanzania People's Defence Force (TPDF) moved to occupy West Nile Region, it recognized the enmity between the West Nile natives and the UNLA,[6] as the latter largely consisted of Acholi and Langi troops.[2] The TPDF restricted the involvement of UNLA troops during the operation.[6] With the exception of a clash at Bondo, the TPDF encountered no resistance while securing the West Nile Region.[7][8] The Tanzanians were informed by locals that instead of making a last stand in the area, thousands of Ugandan soldiers had fled to Sudan and Zaire (present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo).[9] Even though its troops were accused of looting,[10] the TPDF behaved mostly disciplined in the West Nile Region, and made an effort to improve the security.[11] Many civilian refugees consequently returned, hoping that they would be left alone.[10] However, tribal militias and UNLA troops soon moved into the area, and started to attack local communities, seeking revenge for the abuses committed by Amin's regime.[12][13][14] The unrest and dissatisfaction was furthered by the UNLF government's refusal to employ Amin-era soldiers in its armed forces, forcing most ex-UA members to seek new jobs or join the Amin loyalists in exile.[15] UNLA and TPDF soldiers also intimidated, arrested, harassed, and killed former UA soldiers, in addition to confiscating and destroying property belonging to ex-soldiers including houses, schools, and hospitals.[16][17][18] Many West Nile natives consequently resented the new authorities, feeling marginalized, unsafe, and wishing for revenge.[19]

At the same time, Uganda became embroiled in a political crisis, as President Lule struggled with other political figures and the UNLA for control.[20] As he tried to exert his powers and circumvent the UNLF's powerful National Consultative Committee, the latter removed him from office on 20 June 1979.[21] Lule was replaced by Godfrey Binaisa who lacked his own power base. In May 1980, Binaisa was also deposed and Uganda fell under the control of the UNLF's Military Commission that was supposed to rule until the scheduled December 1980 general election.[22][23] Both Lule as well as Binaisa had tried to limit the violent abuses in the West Nile Region, with the former ordering the Tanzanians to only station "moderate and unprejudiced soldiers" there. With these two removed from power, extremist Acholi and Langi factions grew in influence.[24] The situation was further complicated by the upcoming elections, as political parties and various factions struggled to rally supporters, intimidate opponents, and gain possible legal as well illegal advantages. Ex-President Obote returned to Uganda and began reorganising the Uganda People's Congress (UPC) in preparation for general elections.[25]

Prelude

[edit]The Uganda Army remnants in Sudan and Zaire intended to launch an insurgency and retake Uganda.[9] Many ex-soldiers started to operate as bandits, crossing the borders into Uganda to plunder.[26] Groups of UA raiders were active in Karamoja[27][28] as well as the West Nile Region. In the latter region, the situation initially remained under control, as the TPDF garrisons were capable of easily eliminating UA groups. However, the TPDF was trying to reduce its presence, and gradually handed over responsibility for the West Nile Region to the UNLF government's security forces[26] in April 1980.[29] Even though the UNLF's Military Commission supported the move and wanted the TPDF troops transferred to other areas,[1] the handover was hampered by the UNLA soldiers' reluctance to engage the UA raiders in combat. UNLA patrols repeatedly fled without firing their weapons upon encountering smaller UA groups. To the frustration of Tanzanian officers, UNLA soldiers reasoned that the TPDF had been "hired" to take care of the Uganda Army, making them unwilling to risk their lives in battle.[26] The new UNLA garrisons also behaved much more brutally toward the West Nile Region's population.[11] According to researcher A. Kasozi, an assassination attempt on Obote during an election campaign rally at the town of Koboko in August 1980 provoked harsh repression by the UNLA and Acholi/Langi militias, furthering the local discontent.[24]

By August and September 1980, the UA remnants were banding together in Sudan and Zaire and preparing a full invasion of the West Nile Region.[19][26][a] Their 7,100-strong force never adopted an official name, but is generally called "Uganda Army" as it consisted for the most part of old troops of Amin's Uganda Army (it was also known as "West Front" or "Western Nile Front").[22] Even though ex-UA chief of staff Isaac Lumago later claimed that the UA had remained structurally "intact" in exile,[30] the rebels factually operated as independent bands[31][32] that were loyal to numerous officers who had previously served under Amin[31] such as Emilio Mondo, Isaac Lumago, Isaac Maliyamungu,[31] Elly Hassan,[32] Christopher Mawadri,[31][33] and Moses Ali.[34] These bands had no political program, and were primarily motivated by the "feeling of insecurity and revenge" among West Nile natives.[19] Journalists Tony Avirgan and Martha Honey disparagingly described the rebels as "nothing more than a large pack of looters and bandits".[6] Having announced his intention to eventually resume power in Uganda,[35] Amin arranged for the Uganda Army remnants to receive money from Saudi Arabia in preparation for the planned cross-border attack.[26] The Ugandan government would later claim that the pro-Amin forces were supported by Zaire, Sudan, and Saudi Arabia.[2] Juma Oris, an Amin loyalist who played a major role in setting up the rebel coalition, was known to have good contacts to the Sudanese security services.[36]

Campaign

[edit]Uganda Army invasion

[edit]On 6 October, one week before the offensive was to commence, about 500 UA rebels crossed the border and attacked Koboko. The 200-strong UNLA garrison was on parade at the time and was unarmed; the rebels massacred the soldiers.[6][1] One local civilian and the Makerere University's Refugee Law Project later reported that the insurgents also assaulted other towns such as Aringa, Yumbe, and Bondo around the same time.[19][37] Word of the attacks quickly spread to other UNLA garrisons in West Nile, who then fled to the Nile River, leaving the Uganda Army's advance mostly unopposed.[6][38] Many UNLA troops initially sought refuge at Bondo where one of the region's main barracks was located.[1] Eventually, five UA detachments attacked Bondo in force;[39] according to researchers Tom Cooper and Adrien Fontanellaz, this operation took place on 8 October.[22] The local UNLA troops were again caught by surprise during a morning parade; most were killed, and the rest fled in disarray.[40]

The rebels were welcomed by much of the local population,[6] although many civilians fled across the borders to Sudan and Zaire,[41] considering the UA militants little better than the pro-government forces.[42] On 8 or 9 October, Arua as well as its airport were reportedly attacked and conquered[22][41] by a combined force coming from Sudan and Zaire; after it fell, the civilians initially hailed the UA troops "liberators".[41] To the frustration of the locals, however, the invaders immediately started to loot coffee and transport it abroad.[42] This incident greatly damaged the insurgents' reputation among the civilians, and different rebel groups would later blame each other for the looting.[43] The insurgents also assaulted and burned down Moyo.[41] Kasozi stated that the local UNLA battalion had already fled at this point,[24] whereas the Makerere University's Refugee Law Project claimed that the town's UNLA garrison was overrun by UA forces.[37] Terego, Maracha, and Oraba were also captured by the insurgents.[44]

By mid-October, Ugandan government officials believed Koboko, Arua, Bondo, Moyo, and Lodonga to be controlled by the rebel troops.[35] The Minority Rights Group International[1] and Kasozi argued that there was a "popular uprising" in support of the invasion, and many settlements actually fell to revolting locals instead of the rebels.[24] As the insurgents knew that they could not hold the captured territory against a full UNLA counter-offensive, they mostly retreated back into Sudan after a few days[22] with a large amount of loot.[6] East of the Nile, the invasion caused fighting between armed Madi and Acholi civilians.[41] In response to the invasion, the UNLA commandeered vehicles in the capital Kampala, while Minister of Foreign Affairs Otema Allimadi handed a diplomatic note of protest to the ambassadors of Zaire and Sudan.[35] Military police personnel set up posts at all roads leading out of the West Nile Region to stop the fleeing UNLA soldiers.[45]

UNLA counteroffensive and massacres

[edit]You, who have made us suffer, now it is your turn to die.

The UNLA began its counteroffensive on 12 October accompanied by TPDF troops,[6] advancing from Pakwach northward.[24] This force was backed by thousands[1] of Acholi and Langi militants and "volunteers",[24] including the Kitgum militia.[6][46] The latter group was an exclusively Acholi private army, regarded as sympathetic toward the UPC.[47] The counteroffensive only encountered significant resistance at Bondo, where six Tanzanians were killed during an eight-hour battle.[6] Lieutenant Colonel Elly Aseni was among the Uganda Army fighters who died in combat near Bondo.[48] Even though the rebels had mostly fled, the UNLA began brutal reprisals.[24] Considering the local population hostile, UNLA troops engaged in a campaign of destruction and looting across the West Nile, while Tanzanian officers tried in vain to restrain them.[6] Many settlements in the region were torched, women raped, grain storages destroyed, and civilians driven into huts which were set on fire.[24] Everything portable was carried away by the troops and militiamen.[2] UNLA soldiers leveled the town of Arua,[6] reportedly leaving only its Catholic Cathedral standing.[2] A TPDF soldier stated that when he and his comrades arrived at the town, it had been "wiped out" by UNLA soldiers and entirely depopulated, with women, children, and even dogs shot dead and left rotting in the streets. The destruction was only halted when Tanzanian troops intervened.[49]

The punitive expedition also targeted the territories inhabited by the Madi, namely Moyo and the areas east of the Nile. In Moyo, UNLA soldiers were reportedly seen walking around with the cut-off genitals of their victims at their belts, while east of the river militiamen and their families plundered and stole cattle.[24] The UNLA soldiers even crossed the border to Zaire in pursuit of the insurgents, clashing with UA guerrillas "near" Isiro. Instead of evicting the Ugandan intruders or stopping the clashes, the local Zairian Armed Forces (Forces Armées Zaïroises, FAZ) garrison fled westward.[50] However, UNLA's attempt to dislodge the UA remnants from the Sudanese border town of Kaya failed, allowing it to remain a "rebel stronghold" from where the insurgents could strike into Uganda and set up ambushes at the Kaya-Oraba road.[44]

The exact civilian death toll of the UNLA counter-attack remains unknown. Estimates ranged from 1,000[6] to 30,000.[24] Among the victims were Martin Okwera, Uganda Airlines branch manager for Arua, and his entire family of ten as well as relatives of cabinet members Anthony Ochaya and Moses Apiliga.[51] The brutality of the UNLA provoked the flight of over 250,000 refugees to Sudan and Zaire,[6] and inspired further unrest, as peasants and ex-soldiers took up arms to defend their lands from the government forces.[32] Amid the unrest, communication between the West Nile Region and the outside world largely collapsed.[41]

Aftermath

[edit]Political effects

[edit]Following the October invasion, Tanzanian Foreign Minister Benjamin Mkapa flew to Kampala and met with the Military Commission, informing them of the Tanzanian government's "dismay" at the widespread destruction committed by UNLA in the West Nile Region.[2] The Ugandan government sent Ministers Apiliga and Anthony Butele to investigate the situation in West Nile. They toured the region from October to November 1980, and wrote a report that detailed the massive damage as well as the brutality of the UNLA, commenting that "most civilians are shot on sight". Even though this report was seconded by other government officials who visited the region in the next months, the Ugandan government arrested Uganda Times journalist Ben Bella Elakut for writing about the massacres.[52] One UNLA officer, Lieutenant Colonel Ojul, was arrested due to his involvement in the massacres around Moyo, but quickly released.[1] Researcher Gardener Thompson concluded that the UNLF government, "if not directly sponsored [the massacre], evidently condoned" it.[53]

The chaos in the West Nile Region severely disrupted the local preparations for the upcoming elections. Voter registration in the area had been scheduled for 6 October, but consequently became impossible, as did any meaningful elections. The UPC took advantage of the chaos: First, election officials accepted the UPC candidates and disqualified all candidates of other parties, most importantly the Democratic Party.[54] When they tried to register, DP candidates were denied the usual security measures by the authorities, and instead arrested and harassed by UNLA soldiers and militiamen based on suspicions that they were rebel supporters.[55] Their registrations were also shut down based on a lack of tax documents, despite these having been destroyed during the fighting.[54][55] Secondly, the lack of voter registration meant that there were no actual elections in West Nile, yet the UPC parliamentary candidates were declared the unopposed winners of the local constituencies.[54] Aided by these and other irregularities, the UPC won the December 1980 elections, and formed a government with Milton Obote as president.[56] The international Commonwealth Observer Groups sent to observe the election criticized the exclusion of DP candidates for the West Nile election, but did not mention the fighting and massacre at all, and overall praised the election's conduct.[57]

The results were strongly disputed by other candidates, leading to increasing strife. Several political factions claimed electoral fraud, and believed themselves to be proven correct when Obote immediately launched a campaign of political repression.[58] In 1981, President Obote expressed "pride" at the massacre in the West Nile Region, and warned the Baganda people that the same could happen to them.[53]

Course of the insurgency

[edit]The October campaign in West Nile marked the de facto beginning of the Ugandan Bush War, a civil war which would last until 1985.[22] Following the disputed elections, the northern rebellion would be joined by insurgencies in southern Uganda, organized by anti-Obote opposition groups.[58]

The Uganda Army launched its next offensive just before the December 1980 elections. In one of their most daring actions, the rebels ambushed Obote as he was touring the West Nile region. They almost killed him and Tito Okello, a high-ranking UNLA commander. This time, the Uganda Army also held the areas it captured in West Nile, and set up a parallel government after retaking Koboko. After about one month of combat, the insurgents had captured most of West Nile, leaving only some towns under UNLA control.[22] However, many rebels focused more on looting the area and taking the plunder back to Zaire and Sudan than on fighting the UNLA.[32] In addition, political differences began to emerge among the rebels, and the Uganda Army fully fractured into two rival movements, known as the Former Uganda National Army (FUNA) and Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF).[59] By February 1981, the two groups were fighting each other.[60] Meanwhile, Acholi militiamen committed further massacres in the Madi-inhabited areas in February and March 1981, even as UNLA control eroded in the area.[1] When the last Tanzanian troops left Uganda in October 1981, the rebels made larger incursions into the West Nile District.[61] Heavy fighting continued and caused further damage to the area.[61][59] By September 1981, at least 140,000 Ugandan refugees had relocated to the Zairian border town of Aru, while 250,000 had fled to Sudan. Large sections of the West Nile Region were depopulated, and Arua remained in ruins.[50] The Ugandan government was not able to contain the West Nile insurgency until 1982.[61]

Notes

[edit]- ^ The foundation of the Former Uganda National Army (FUNA) and Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) have been dated to this time.[19][24]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Meynell 1984, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f Mutibwa 1992, p. 137.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 146.

- ^ Roberts 2017, p. 163.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 187.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 225.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 192–196.

- ^ "Troops Take Over Arua". African Recorder. Vol. 18. 1979. p. 5126.

- ^ a b Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 194–195.

- ^ a b Harrell-Bond 1982, p. 7.

- ^ a b Leopold 2005, pp. 54–55.

- ^ Jackson 1999, pp. 294–295.

- ^ Otunnu 2017, p. 45.

- ^ Decker 2014, p. 168.

- ^ Harrell-Bond 1982, p. 7–8.

- ^ Abidi 2002, p. 176.

- ^ Harrell-Bond 1982, p. 8.

- ^ Refugee Law Project Working Paper 2014, pp. 4, 6.

- ^ a b c d e Abidi 2002, p. 166.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 197.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 198–200.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, p. 39.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 201, 217–218.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kasozi 1994, p. 177.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 221.

- ^ a b c d e Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 224.

- ^ Ross, Jay (7 June 1980). "Diary of Anguished Trip To Land of the Damned". The Washington Post. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ Muhereza, Frank Emmanuel (December 1998). "Violence and the State in Karamoja: Causes of Conflict, Initiative for Peace". Cultural Survival. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- ^ Leopold 2005, p. 54.

- ^ United Press International (12 August 1985). "Amin's Generals Seek Amnesty for Him". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- ^ a b c d Africa Confidential 1981, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d Harrell-Bond 1982, p. 9.

- ^ Harrell-Bond 1982, p. 6.

- ^ Africa Confidential 1981, p. 9.

- ^ a b c Worrall, John (18 October 1980). "Idi Amin bid for comeback in Uganda seen". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Leopold 2005, p. 44.

- ^ a b Refugee Law Project Working Paper 2014, p. 4.

- ^ Kutesa 2006, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Kutesa 2006, p. 49.

- ^ Kutesa 2006, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c d e f Jackson 1999, p. 295.

- ^ a b Refugee Law Project Working Paper 2014, p. 9.

- ^ Refugee Law Project Working Paper 2014, pp. 4, 6, 9.

- ^ a b Kisembo 2021, p. 208.

- ^ Kutesa 2006, p. 51.

- ^ Mutibwa 1992, pp. 137, 141.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 212.

- ^ Faustin Mugabe (5 July 2015). "Senior officers Arube, Aseni attempt to overthrow Amin – Part I". Daily Monitor. Archived from the original on 30 March 2019. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ^ Mutibwa 1992, p. 138.

- ^ a b Dash, Leon (13 November 1981). "Refugees Set in Motion by Amin Disrupt Uganda, Zaire, Sudan". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 November 2021.

- ^ Mutibwa 1992, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Kasozi 1994, pp. 177–178.

- ^ a b Thompson 2015, p. 183.

- ^ a b c Avirgan & Honey 1983, p. 226.

- ^ a b Mutibwa 1992, p. 141.

- ^ Avirgan & Honey 1983, pp. 221, 226, 230.

- ^ Thompson 2015, p. 184.

- ^ a b Cooper & Fontanellaz 2015, pp. 39–40.

- ^ a b Kasozi 1994, pp. 178–179.

- ^ Refugee Law Project Working Paper 2014, p. 7.

- ^ a b c Avirgan, Tony (3 May 1982). "Amin's army finally defeated". United Press International. Retrieved 8 May 2019.

Works cited

[edit]- Africa Confidential 22. Miramoor Publications Limited. 1981.

- Abidi, Syed (2002). Living Beyond Conflict: For Peace and Tolerance. Kampala: ABETO. ISBN 978-9970-822-00-3.

- Avirgan, Tony; Honey, Martha (1983). War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Dar es Salaam: Tanzania Publishing House. ISBN 978-9976-1-0056-3.

- Cooper, Tom; Fontanellaz, Adrien (2015). Wars and Insurgencies of Uganda 1971–1994. Solihull: Helion & Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-910294-55-0.

- Decker, Alicia C. (2014). In Idi Amin's Shadow: Women, Gender, and Militarism in Uganda. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-4502-0.

- Harrell-Bond, Barbara (1982). "Ugandan Refugees in the Sudan. Part I: The long journey" (PDF). UFSI Reports (48). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2016.

- Jackson, Ivor C. (1999). The Refugee Concept in Group Situations. The Hague, London, Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-411-1228-6.

- Kasozi, A. (1994). Social Origins of Violence in Uganda, 1964–1985. McGill-Queen's Press. ISBN 9780773564879.

- Kisembo, Charles (2021). Political Uncertainty, Violence and Hope in Uganda: A Personal Account. Singapore: Strategic Book Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62857-868-3.

- Kutesa, Pecos (2006). Uganda's Revolution, 1979-1986: How I Saw it. Fountain Publishers. ISBN 978-9970025640.

- Leopold, Mark (2005). Inside West Nile. Violence, History & Representation on an African Frontier. Oxford: James Currey. ISBN 978-0-85255-941-3.

- Meynell, Charles (1984). Uganda and Sudan. London: Minority Rights Group International. ISBN 9780946690244.

- Mutibwa, Phares Mukasa (1992). Uganda Since Independence: A Story of Unfulfilled Hopes. Africa World Press. ISBN 9780865433571.

- "Negotiating Peace: Resolution of Conflicts in Uganda's West Nile Region" (PDF). Refugee Law Project Working Paper (12). June 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 May 2016.

- Otunnu, Ogenga (2017). Crisis of Legitimacy and Political Violence in Uganda, 1979 to 2016. Chicago: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-3-319-33155-3.

- Roberts, George (2017). "The Uganda–Tanzania War, the fall of Idi Amin, and the failure of African diplomacy, 1978–1979". In Anderson, David M.; Rolandsen, Øystein H. (eds.). Politics and Violence in Eastern Africa: The Struggles of Emerging States. London: Routledge. pp. 154–171. ISBN 978-1-317-53952-0.

- Thompson, Gardner (2015). African Democracy: Its Origins and Development in Uganda, Kenya and Tanzania. Oxford: Fountain Publishers. ISBN 978-9970-25-311-1.

- Ugandan Bush War

- 1980 in Uganda

- Conflicts in 1980

- October 1980 events in Africa

- Massacres in Uganda

- Military operations involving Uganda

- Military operations involving Tanzania

- Massacres in 1980

- Arson in Uganda

- Arson in 1980

- Looting in Africa

- Wartime sexual violence in Africa

- 1980 fires

- Attacks on buildings and structures in 1980

- Attacks on buildings and structures in Uganda

- 20th-century mass murder in Uganda