Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2019 May 23

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < May 22 | << Apr | May | Jun >> | May 24 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

May 23

[edit]What color is a safelight?

[edit]On TV it is usually red, and I'm wondering if this is the same red which is one of the three primary colors of light?— Vchimpanzee • talk • contributions • 21:44, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

- We have an article on safelights. The exact type and exact color depend on the purpose. Many old-fashioned photographic development labs used a red or reddish colored light. Many modern industrial labs that work with photosensitive photoresists in the electronics industry use a yellow or amber light. Professionals who work with specific photographic or photoreactive film chemicals usually get specialized technical data from their chemical vendor to guide their light color and fixture choices. Here's technical information for DuPont RISTON photopolymer, including spectra and lamp recommendations. Here's safe light filter recommendations for KODAK motion picture film, and here's a guide to dark room illumination. Nimur (talk) 21:59, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

- The Wikipedia article didn't get very specific, but does any of that relate to the red that is a primary color of light? In fact, Wikipedia doesn't even seem to cover that subject.— Vchimpanzee • talk • contributions • 22:28, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

- I don't think any of those even mentioned the color red. I can't imagine how people develop film in total darkness, but that was the recommendation for certain cases.— Vchimpanzee • talk • contributions • 22:33, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

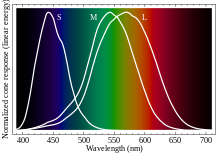

- There is no "red that is a primary color of light", or at least not exactly. There are three different kind of cone cells, which have different response curves to wavelengths of light in the visible range. One of the three types has the strongest response in the longer wavelengths, and in some (probably oversimplified) sense, that is what defines what we call "red". But lots of different wavelengths will provoke at least some response from those cells.

- So "red as a primary color" is more about the human eye than it is about light per se.

- I expect there's more information at color vision. --Trovatore (talk) 23:13, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

- Photographic film is sensitive to red light. But it only has to be in total darkness when you open the camera, and transfer the film to the developer spindle and then once it is inside the developer it is safe from light. Then once the fixer has done its job, it is safe to open. The black and white photopaper was safe in red light. Graeme Bartlett (talk) 23:18, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

- I don't think any of those even mentioned the color red. I can't imagine how people develop film in total darkness, but that was the recommendation for certain cases.— Vchimpanzee • talk • contributions • 22:33, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

- The Wikipedia article didn't get very specific, but does any of that relate to the red that is a primary color of light? In fact, Wikipedia doesn't even seem to cover that subject.— Vchimpanzee • talk • contributions • 22:28, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

- It's unrelated to primary colours (except when it isn't...).

- A safelight can be any colour (if there are any) to which the photographic emulsion is insensitive. In the "classic" example, this was red light. That's because red is long wavelength, thus low energy photons (see Photon#Physical properties). Early emulsions were orthochromatic and insensitive to red light (still an improvement, because earlier ones had only been sensitive to blue light). This had given rise to photographic grey, a deliberate painting of some objects (such as brand new steam locomotives) in a pale grey which photographed well with these early emulsions.

- This sensitivity is a linear series, based on the quantum behaviour of the photon (long wavelength, low energy) and these red photons simply not having enough energy to activate the emulsion.

- Primary colours are an artefact of the human eye and its three [sic] types of colour sensitive cones. Speaking in terms of physics, monochrome emulsions and safelights, there are no such things. Andy Dingley (talk) 23:22, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

- There are two types of emulsion in use for typical processes: film (usually a negative film) and then photographic paper used to produce the print. Safelights are (usually) only applicable to the darkroom printing process onto paper. The film is handled in total darkness. Usually this is in a small light-proof developing tank which is loaded in the dark, then allows the chemical handling to be done in daylight.

- The film could be "black and white", more precisely "monochromatic", but it's still sensitive to a wide range of colours. Early emulsions (to mid 20th century) were orthochromatic, but panchromatic emulsions were developed later to give a more realistic (i.e. matching the behaviour of the rods in the human eye) mapping of colour onto brightness. These were red-sensitive and although even ortho film was usually handled in darkness, these couldn't be used with a human-friendly safelight. They were however insensitive to infra-red light and some auto-processing machines used IR LEDs and detectors to read information coded on the film edge, even while it was in the camera or during processing.

- In Victorian times and wet glass plate processes, emulsions were not only just sensitive to blue light, but weren't very sensitive at all. A dim light, such as a candle or oil lamp, could be used as a safe worklight. Although this would eventually have fogged the plate, it would take too long to be a problem.

- Printing paper emulsions didn't have to be daylight sensitive, or even very sensitive at all, as they're exposed via an enlarger with a bright lamp of any desired colour.

- For black & white processing, red safelights are generally used. Some processes have a wider range of sensitivity, so a "deep red" (i.e. longer wavelength) safelight is needed, which is awkward as it's getting to the range where humans don't see too well either. Some processes vary the colour of the enlarger light (with a set of yellow filters) in order to control the contrast ratio of the printing process (Paper used to be made in a range of fixed contrast ratios, but the multigrade papers allowed one paper to be used for all of them). These could though be fussy about safelights.

- Colour printing paper obviously needs to respond to a range of colours. It's made from a laminate of differently responsive layers (see Color photography#Three-color processes): usually the complementary colours though, cyan, magenta and yellow, not RGB (see Color photography#Subtractive color and CMYK color model). Safelights are difficult, but a dim yellow-green one was usable. As the triplet colours here were chosen to match human colour perception, and the safelight is having to match a gap between those, then we could now say that safelight colours are in fact derived from human eye responses.

- A further sort of safelight is used in microelectronics fabrication, mostly IC production but also sometimes for circuitry. The photoresists used here as UV-sensitive by design, but also overlap into the blue visible spectrum. The safelight here is a rather bilious bright yellow, much brighter than used for photography. It could just as well be red (the photoresists don't care) but humans see poorly in red and these are precision labs, where good vision is needed. Andy Dingley (talk) 23:34, 23 May 2019 (UTC)

In B&W darkrooms you usually use red (sometimes amber) safelight with enlarging paper that's not sensitive to it. For film you use total darkness. It's not too bad--you shut off the lights and load the developing reel by feel, and you can do it with a changing bag if you don't have a darkroom. Just practice loading reels once or twice with the lights on and with scrap film to pick up the technique and you're good to go. Then you put the reel into the developing tank (which is light tight) and you can turn on the lights.

For color enlarging you do the enlargement in darkness but then you usually load the exposed enlarging paper into a machine or light-tight drum for processing, so you don't have to fumble around with trays of liquid chemicals in the dark. You do use the chemical trays for B&W paper, but with safelight so you can see what you're doing. 67.164.113.165 (talk) 18:45, 24 May 2019 (UTC)

- Anyway, all I really want is to ask whether the color I saw in a darkroom on TV was the color that is considered a primary color of light, in the sense that green and a certain shade of blue are added to this red to produce white light, or in the sense that old televisions have these three colors. I don't know what modern TVs do. I saw what I am describing in World Book Encyclopedia but I don't know if Wikipedia has anything comparable. In World Book, three colored circles were projected on a wall or screen in a manner similar to this. Where the red I am describing overlapped with green, the light was yellow. Where it overlapped with blue, the light was magenta. And when green and blue overlapped, the light was cyan. In a small area all three colors overlapped and the result was white light.— Vchimpanzee • talk • contributions • 16:32, 25 May 2019 (UTC)

- There's no exact wavelength triplet that is the primary colors. It might not work as well if your primaries have a touch of cyan or yellow or indigo or magenta to the naked eye. Sagittarian Milky Way (talk) 18:05, 25 May 2019 (UTC)

- See Color vision for more.

- In the "classic" case for printing B&W paper, the safelight is red because that's the longest wavelength in the human visible range, thus the lowest energy photons, thus the least chance of affecting the paper. It's not a "primary colour".

- In the rarer case of a colour-safe-safelight for some more sensitive colour paper emulsions, the safelight is the yellow-green colour which is at the peak of the L curve here. That's because it's both a minimum of the paper's sensitivity (between two colours it is sensitive to) and also something of a peak for what humans can see. But those are pretty useless safelights, as they're so dim. This still isn't a primary colour, but it is now related to the human eye's behaviour, not just quantum physics. Andy Dingley (talk) 10:17, 26 May 2019 (UTC)