2010s in political history

An editor has nominated this article for deletion. You are welcome to participate in the deletion discussion, which will decide whether or not to retain it. |

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| +... |

2010s in political history refers to significant political and societal historical events of the 2010s, presented as a historical overview in narrative format.

World events

[edit]Arab Spring

[edit][[File:

Protesters gathered at Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt, 9 February 2011;

Habib Bourguiba Boulevard, protesters in Tunis, Tunisia, 14 January 2011;

Dissidents in Sanaa, Yemen, calling for president Ali Abdullah Saleh to resign on 3 February 2011;

Crowds of hundreds of thousands in Baniyas, Syria, 29 April 2011|thumb|]]

The Arab Spring (Arabic: الربيع العربي, romanized: ar-rabīʻ al-ʻarabī) or the First Arab Spring (to distinguish from the Second Arab Spring) was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began in Tunisia in response to corruption and economic stagnation.[1][2] From Tunisia, the protests then spread to five other countries: Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Syria and Bahrain. Rulers were deposed (Zine El Abidine Ben Ali of Tunisia in 2011, Muammar Gaddafi of Libya in 2011, Hosni Mubarak of Egypt in 2011, and Ali Abdullah Saleh of Yemen in 2012) or major uprisings and social violence occurred including riots, civil wars, or insurgencies. Sustained street demonstrations took place in Morocco, Iraq, Algeria, Lebanon, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman and Sudan. Minor protests took place in Djibouti, Mauritania, Palestine, Saudi Arabia and the Western Sahara.[3] A major slogan of the demonstrators in the Arab world is ash-shaʻb yurīd isqāṭ an-niẓām! (Arabic: الشعب يريد إسقاط النظام, lit. 'the people want to bring down the regime').[4]

The wave of initial revolutions and protests faded by mid to late 2012, as many Arab Spring demonstrations were met with violent responses from authorities,[5][6][7] pro-government militias, counterdemonstrators, and militaries. These attacks were answered with violence from protesters in some cases.[8][9][10] Multiple large-scale conflicts followed: the Syrian civil war;[11][12] the rise of ISIS,[13] insurgency in Iraq and the following civil war;[14] the Egyptian Crisis, election and removal from office of Mohamed Morsi, and subsequent unrest and insurgency;[15] the Libyan Crisis; and the Yemeni crisis and subsequent civil war.[16] Regimes that lacked major oil wealth and hereditary succession arrangements were more likely to undergo regime change.[17]

A power struggle continued after the immediate response to the Arab Spring. While leadership changed and regimes were held accountable, power vacuums opened across the Arab world. Ultimately, it resulted in a contentious battle between a consolidation of power by religious elites and the growing support for democracy in many Muslim-majority states.[18] The early hopes that these popular movements would end corruption, increase political participation, and bring about greater economic equity quickly collapsed in the wake of the counter-revolutionary moves by foreign state actors in Yemen,[19] the regional and international military interventions in Bahrain and Yemen, and the destructive civil wars in Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Yemen.[20]

Some have referred to the succeeding and still ongoing conflicts as the Arab Winter.[11][12][14][15][16] Recent uprisings in Sudan and Algeria show that the conditions that started the Arab Spring have not faded and political movements against authoritarianism and exploitation are still occurring.[21] Since late 2018, multiple uprisings and protest movements in Algeria, Sudan, Iraq, Lebanon, and Egypt have been seen as a continuation of the Arab Spring.[22][23]

As of 2024, multiple conflicts are still continuing that might be seen as a result of the Arab Spring. The Syrian Civil War has caused massive political instability and economic hardship in Syria, with the Syrian pound plunging to new lows.[24] In Libya, a major civil war concluded, with foreign powers intervening.[25][26] In Yemen, a civil war continues to affect the country.[27] In Lebanon, a major banking crisis is threatening the country's economy as well as that of neighboring Syria. In December 2024, opposition groups in the Syrian Civil War launched offensives against the Syrian government, resulting in Bashar Al-Assad being overthrown, the Assad regime ending after over 50 years, the fall of Damascus, and the 2024 Israeli invasion of Syria.War on extremists in Iraq

[edit]The War in Iraq (2013–2017) was an armed conflict between Iraq and its allies and the Islamic State. Following December 2013, the insurgency escalated into full-scale guerrilla warfare following clashes in the cities of Ramadi and Fallujah in parts of western Iraq, and culminated in the Islamic State offensive into Iraq in June 2014, which lead to the capture of the cities of Mosul, Tikrit and other cities in western and northern Iraq by the Islamic State. Between 4–9 June 2014, the city of Mosul was attacked and later fell; following this, Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki called for a national state of emergency on 10 June. However, despite the security crisis, Iraq's parliament did not allow Maliki to declare a state of emergency; many legislators boycotted the session because they opposed expanding the prime minister's powers.[28] Ali Ghaidan, a former military commander in Mosul, accused al-Maliki of being the one who issued the order to withdraw from the city of Mosul.[29] At its height, ISIL held 56,000 square kilometers of Iraqi territory, containing 4.5 million citizens.[30]

The war resulted in the forced resignation of al-Maliki in 2014, as well as an airstrike campaign by the United States and a dozen other countries in support of the Iraqi military,[31] participation of American and Canadian troops (predominantly special forces) in ground combat operations,[32][33] a $3.5 billion U.S.-led program to rearm the Iraqi security forces,[34] a U.S.-led training program that provided training to nearly 200,000 Iraqi soldiers and police,[35] the participation of the military of Iran, including troops as well as armored and air elements,[36] and military and logistical aid provided to Iraq by Russia.[31] On 9 December 2017, Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi announced victory over the Islamic State.[37][38][39][40] The Islamic State switched to guerrilla "hit and run" tactics in an effort to undermine the Iraqi government's effort to eradicate it.[41][42][43] This conflict is interpreted by some in Iraq as a spillover of the Syrian Civil War. Other Iraqis and observers see it mainly as a culmination of long-running local sectarianism, exacerbated by the 2003–2011 Iraq War, the subsequent increase in anti-Sunni sectarianism under Prime Minister al-Maliki, and the ensuing bloody crack-down on the 2012–2013 Iraqi protests.[44]Global issues

[edit]Climate change

[edit]In December 2019, the World Meteorological Organization released its annual climate report revealing that climate impacts are worsening.[45] They found the global sea temperatures are rising as well as land temperatures worldwide. 2019 is the last year in a decade that is the warmest on record.[46] The 2010s were the hottest decade in recorded history, according to NASA and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). 2016 was the hottest year and 2019 was the second hottest.[47]

Global carbon emissions hit a record high in 2019, even though the rate of increase slowed somewhat, according to a report from Global Carbon Project.[48]

International conflict

[edit]Libya

[edit]In early 2011, a civil war broke out in the context of the wider "Arab Spring". The anti-Gaddafi forces formed a committee named the National Transitional Council, on 27 February 2011. It was meant to act as an interim authority in the rebel-controlled areas. After the government began to roll back the rebels and a number of atrocities were committed by both sides,[49][50][51][52][53] a multinational coalition led by NATO forces intervened on 21 March 2011, with the stated intention to protect civilians against attacks by the government's forces.[54] Shortly thereafter, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant against Gaddafi and his entourage on 27 June 2011. Gaddafi was ousted from power in the wake of the fall of Tripoli to the rebel forces on 20 August 2011, although pockets of resistance held by forces loyal to Gaddafi's government held out for another two months, especially in Gaddafi's hometown of Sirte, which he declared the new capital of Libya on 1 September 2011.[55] His Jamahiriya regime came to an end the following month, culminating on 20 October 2011 with Sirte's capture, NATO airstrikes against Gaddafi's escape convoy, and his killing by rebel fighters.[56][57]

Syria

[edit]During the Syrian civil war, a number of foreign countries, such as Iran, Russia, Turkey, and United States, became directly involved. Iran, Russia, and Hezbollah supported the Syrian Arab Republic militarily, with Russia launching its airstrikes and ground operations since September 2015. The U.S.-led international coalition, established in 2014 with the declared purpose of countering the IS organization, was conducting airstrikes primarily against IS and sometimes against government and pro-Assad forces. Since 2015, the coalition deployed special forces and artillery units for their campaign, in the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria and Al-Tanf deconfliction zone; and materially and logistically supported their armed wings, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and Army of Free Syria respectively. Turkish military fought the SDF, IS, and the Assad government since 2016, but also actively supported the Syrian National Army (SNA) and would occupy parts of northern Syria while engaging in significant ground combat. Between 2011 and 2017, fighting from the Syrian civil war spilled over into Lebanon as opponents and supporters of the Syrian government traveled to Lebanon to fight and attack each other on Lebanese soil. While officially neutral, Israel exchanged border fire and carried out repeated strikes against Hezbollah and Iranian forces, whose presence in western Syria it viewed as a threat.[58][59]

Nagorno-Karabakh

[edit]The 2010 Nagorno-Karabakh clashes were a series of exchanges of gunfire that took place on February 18 on the line of contact dividing Azerbaijani and the Karabakh Armenian military forces. As a result, three Azerbaijani soldiers were killed and one wounded.[60] Both sides suffered more casualties in the 2010 Mardakert clashes, the 2012 border clashes, and the 2014 clashes.

The 2016 Nagorno-Karabakh conflict began along the Nagorno-Karabakh line of contact on 1 April 2016 with the Artsakh Defence Army, backed by the Armenian Armed Forces on one side and the Azerbaijani Armed Forces on the other. The clashes occurred in a region that is disputed between the self-proclaimed Republic of Artsakh and the Republic of Azerbaijan. Officially Baku reported the loss of 31 servicemen without publishing their names. Nevertheless, Armenian sources claimed much higher numbers varying between 300 and 500.[61] The Ministry of Defence of Armenia reported the names of 92 military and civilian casualties, in total.[62] The US State Department estimated that a total of 350 people, both military and civilian, had died.[63]

The 2018 Armenian–Azerbaijani clashes[a] began on 20 May 2018 between the Armenian Armed Forces and Azerbaijani Armed Forces. Azerbaijan stated to have taken several villages and strategic positions within the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic.[64]

Ukraine

[edit]In early 2014, the Euromaidan protests led to the Revolution of Dignity and the ousting of Ukraine's pro-Russian president Viktor Yanukovych. Shortly after, pro-Russian unrest erupted in eastern and southern Ukraine. Simultaneously, unmarked Russian troops moved into Ukraine's Crimea and took over government buildings, strategic sites and infrastructure. Russia soon annexed Crimea after a highly disputed referendum. In April 2014, armed pro-Russian separatists seized government buildings in Ukraine's eastern Donbas region and proclaimed the Donetsk People's Republic (DPR) and Luhansk People's Republic (LPR) as independent states, starting the Donbas war. The separatists received considerable but covert support from Russia, and Ukrainian attempts to fully retake separatist-held areas failed. Although Russia denied involvement, Russian troops took part in the fighting. In February 2015, Russia and Ukraine signed the Minsk II agreements to end the conflict, but the agreements were never fully implemented in the years that followed. The Donbas war settled into a violent but static conflict between Ukraine and the Russian and separatist forces, with many brief ceasefires but no lasting peace and few changes in territorial control.

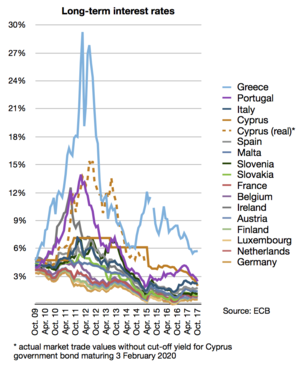

World banking

[edit]Concerns increased about the European Debt Crisis as both Greece and Italy continued to have high levels of public debt. This caused concerned about stability of the Euro. In December 2019, the EU announced that banking ministers from EU member nations had failed to reach agreement over proposed banking reforms and systemic change.[65][66] The EU was concerned about high rates of debt in France, Italy and Spain.[67] Italy objected to proposed new debt bailout rules that were proposed to be added to the European Stability Mechanism.[68]

In the first half of 2019, global debt levels reached a record high of $250 trillion, led by the US and China.[69] The IMF warned about corporate debt.[69] The European Central Bank raised concerns as well.[70]

World trade

[edit]United States-China trade dispute

[edit]A trade dispute between the US and China caused economic concerns worldwide. In December 2019, various US officials said a trade deal was likely before a proposed round of new tariffs took effect on December 15, 2019.[71] US tariffs had a negative effect on China's economy, which slowed to growth of 6%.[71]

United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement

[edit]The United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement[72] is a signed but not ratified free trade agreement between Canada, Mexico, and the United States. The Agreement is the result of a 2017–2018 renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) by its member states.[73] Negotiations "focused largely on auto exports, steel and aluminum tariffs, and the dairy, egg, and poultry markets." One provision "prevents any party from passing laws that restrict the cross-border flow of data".[74] Compared to NAFTA, USMCA increases environmental and labour regulations, and incentivizes more domestic production of cars and trucks.[75] The agreement also provides updated intellectual property protections, gives the United States more access to Canada's dairy market, imposes a quota for Canadian and Mexican automotive production, and increases the duty free limit for Canadians who buy U.S. goods online from $20 to $150.[76]

Africa

[edit]Piracy

[edit]Piracy in the Gulf of Guinea affects a number of countries in West Africa, including Benin, Togo, Côte d'Ivoire, Ghana, Nigeria, and the Democratic Republic of Congo as well as the wider international community. By 2011, it had become an issue of global concern. Pirates are often part of heavily armed criminal enterprises, who employ violent methods to steal oil cargo. In 2012, the International Maritime Bureau and other agencies reported that the number of vessels attacks by West African pirates had reached a world high, with 966 seafarers attacked and five killed during the year.[77]

Piracy off the coast of Somalia occurs in the Gulf of Aden, Guardafui Channel, Somali Sea, in Somali territorial waters and other areas. It was initially a threat to international fishing vessels, expanding to international shipping since the second phase of the Somali Civil War, around 2000. By December 2013, the US Office of Naval Intelligence reported that only nine vessels had been attacked during the year by the pirates, with no successful hijackings.[78] In March 2017, it was reported that pirates had seized an oil tanker that had set sail from Djibouti and was headed to Mogadishu. The ship and its crew were released with no ransom given after the pirate crew learned that the ship had been hired by Somali businessmen.[79]

War on Terror

[edit]The most prominent terrorist groups that are creating a terror impact in Africa include Boko Haram of Nigeria, Cameroon, Chad, and Niger, and Al-Shabaab of Somalia.[80]

Boko Haram has carried out more than 3,416 terror events since 2009, leading to more than 36,000 fatalities. One of the better-known examples of Boko Haram's terror tactics was the 2014 Chibok schoolgirls kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls in Borno State, Nigeria.[80] Boko Haram is believed to have links to al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb dating back to at least 2010. In 2015 the group expressed its allegiance to the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant, which ISIL accepted.[81]

Somalia's al-Shabaab and its Islamic extremism can be traced back to the mid-1970s when the group began as an underground movement opposing the repressive and corrupt regime of Siad Barre. Armed conflict between al-Shabaab and the Somali army – including associated human rights violations – has resulted in slightly over 68 million human displacements.[80] Al-Shabaab is hostile to Sufi traditions and has often clashed with the militant Sufi group Ahlu Sunna Waljama'a. The group has also been suspected of having links with Al-Qaeda in Islamic Maghreb and Boko Haram. Among their best-known attacks are the Westgate shopping mall attack in Nairobi, Kenya, in September 2013 (resulting in 71 deaths and 200 injured) and the 14 October 2017 Mogadishu bombings that killed 587 and injured 316.[82] On September 1, 2014, a U.S. drone strike carried out as part of the broader mission killed al-Shabaab leader Ahmed Abdi Godane.[83]

The Insurgency in the Maghreb refers to Islamist militant and terrorist activity in northern Africa since 2002, including Algeria, Mauritania, Tunisia, Morocco, Niger, Mali, Ivory Coast, Libya, Western Sahara, and Burkina Faso, as well as having ties to Boko Haram in Nigeria. The conflict followed the conclusion of the Algerian Civil War as a militant group became al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). Their tactics have included bombings; shootings; and kidnappings, particularly of foreign tourists. In addition to African units, the fight against the insurgency has been led primarily by the French Foreign Legion, although the U.S. also has over 1,300 troops in the region. Four American soldiers were killed in the October 4, 2017 Tongo Tongo ambush in Niger.[84]

Asia

[edit]Armenia

[edit]The 2011 Armenian protests were a series of civil demonstrations aimed at provoking political reforms and concessions from both the government of Armenia and the civic government of Yerevan, its capital and largest city. Protesters demanded President Serzh Sargsyan release political prisoners, prosecute those responsible for the deaths of opposition activists after the 2008 presidential election and institute democratic and socioeconomic reforms, including the right to organise in Freedom Square in downtown Yerevan. They also protested against Yerevan Mayor Karen Karapetyan for banning the opposition from Freedom Square and barring vendors and traders from the city streets.

Various political and civil groups staged anti-government protests in Armenia in 2013. The first series of protests were held following the 2013 presidential election and were led by the former presidential candidate Raffi Hovannisian. Hovannisian, who, according to official results, lost to incumbent Serzh Sargsyan, denounced the results claiming they were rigged. Starting on 19 February, Hovannisian and his supporters held mass rallies in Yerevan's Freedom Square and other cities. Sargsyan was inaugurated on 9 April 2013, while Hovannisian and thousands of people gathered in the streets of Yerevan to protest it, clashing with the police forces blocking the way to the Presidential Palace.

The 2018 Armenian Revolution was a series of anti-government protests in Armenia from April to May 2018 staged by various political and civil groups led by Nikol Pashinyan (head of the Civil Contract party). Protests and marches took place initially in response to Serzh Sargsyan's third consecutive term as the most powerful figure in the government of Armenia and later against the Republican Party-controlled government in general. On 22 April, Pashinyan was arrested and held in solitary confinement overnight, then released on 23 April, the same day that Sargsyan resigned, saying "I was wrong, while Nikol Pashinyan was right".[85][86] The event is referred to by some as a peaceful revolution akin to revolutions in other post-Soviet states.[87][88][89] On 8 May, Pashinyan was elected Prime Minister by the country's parliament with 59 votes.[90]

Azerbaijan

[edit]The 2011 Azerbaijani protests were a series of demonstrations held to protest the government of President Ilham Aliyev. Common themes espoused by demonstrators, many of whom were affiliated with Müsavat and the Popular Front Party, the main opposition parties in Azerbaijan, included doubts as to the legitimacy of the 2008 presidential election, desire for the release of political prisoners, calls for democratic reforms, and demands that Aliyev and his government resign from power. Azerbaijani authorities responded with a security crackdown, dispersing protests and curtailing attempts to gather with force and numerous arrests.

Gulargate was a 2012–2013 political corruption scandal in Azerbaijan involving civil servants and government officials of various levels, serving in positions as high as the National Assembly of Azerbaijan and the Presidential Administration. It flared up on 25 September 2012 after Azerbaijani lawyer and former university rector Elshad Abdullayev posted a hidden camera video on YouTube showing his meeting with Member of Parliament Gular Ahmadova negotiating a bribe to secure a seat in the National Assembly for Abdullayev in the 2005 parliamentary election. The scandal widened after a series of similar videos involving other officials and other cases of corruption were posted by Abdullayev at later dates, followed by sackings, arrests and deaths of some of those who appeared in the videos.[91]

A protest took place on January 12, 2013, in Baku, Azerbaijan after Azerbaijani Army soldier Ceyhun Qubadov was found dead on January 7, 2013. It was first reported that the cause of death was heart attack. Qubadov's family asked for an investigation as they believed it was a murder.

The 2019 Baku protests were a series of nonviolent rallies on 8, 19 and 20 October in Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan. The protests on 8 and 19 October were organized by the National Council of Democratic Forces (NCDF), an alliance of opposition parties, and called for the release of political prisoners and for free and fair elections. They were also against growing unemployment and economic inequality. Among those detained on 19 October was the leader of the Azerbaijani Popular Front Party, Ali Karimli.

Bangladesh

[edit]The Bangladesh Army reported a failed coup d'état was supposed to take place in January 2012 by rogue military officers and expatriate but was stopped by the Bangladesh army in December 2011.[92][93][94] The coup attempt had apparently been planned over several weeks or months with support of religious fanatics outside of Bangladesh.[95] Military sources said that up to 16 hard-line Islamist officers were involved in the coup, with some of them being detained.[96]

On 28 February 2013, Thursday, the ICT, found Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami leader Delwar Hossain Sayeedi guilty of 8 out of 20 charges leveled against him including murder, rape and torture during the 1971 war of independence[97][98][99] On Sunday and Monday, 3 and 4 March, Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami enforced a 48-hour hartal.[97] Protests led by Jamaate Islami activists and Sayeedi supporters were carried out during these strikes.[97] Bangladesh Nationalist Party supported the strike and called for another daylong strike on 5 March.[100] Police shot dead 31 protestors during the initial clashes.[101] After the verdict of Delwar Hossain Sayidee, attacks on Hindu community occurred in several districts of Bangladesh including Noakhali, Lakshmipur, Chittagong, Comilla, Brahmanbaria, Cox's Bazar, Bagerhat, Gaibandha, Rangpur, Dinajpur, Lalmonirhat, Barisal, Bhola, Barguna, Satkhira, Chapainawabganj, Natore, Sylhet, Manikganj, Munshiganj.[102][103][104] Several temples were vandalized. 2 Hindus died due to injuries in the violence.[105][106]

On 5 May, mass protests took place at Shapla Square in the Motijheel area of capital Dhaka. The protests were organized by the Islamist pressure group, Hefazat-e Islam, who were demanding the enactment of a blasphemy law.[107][108] The government responded to the protests by cracking down on the protesters using a combined force drawn from the police, Rapid Action Battalion and paramilitary Border Guard Bangladesh to drive the protesters out of Shapla Square.[109][110][111] Human Rights Watch and other human rights organizations put the total death toll at above 50.[112] Also from 2013, attacks number of secularist writers, bloggers, and publishers and members of religious minorities such as Hindus, Buddhists, Christians, and Shias were killed or seriously injured in attacks that are believed to have been perpetrated by Islamist extremists.[113][114] These attacks have been largely blamed by extremist groups such as Ansarullah Bangla Team and Islamic State of Iraq and Syria.

A joint operation by Border Guards Bangladesh, Rapid Action Battalion and Bangladesh police took place in different places of Satkhira district to hunt down the activists of Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami. They began on 16 December 2013 and continued after the 2014 Bangladesh election.[115] There are allegations that various formations of the Indian military participated in the crackdown, an allegation that Bangladesh government denies.[116][117]

Following the controversial 2014 Bangladeshi general election, the BNP raised several demands for a second election under a neutral caretaker government. By 5 January 2015, the first anniversary of the election, their demands were not met and the BNP initiated countrywide protests and traffic blockades. After many violent and fatal attacks on the public by alleged BNP protesters, the AL branded the BNP as terrorists and Khaleda Zia was forcefully confined to her office.

Bhutan

[edit]On 16 June 2017 Chinese troops with construction vehicles and road-building equipment began extending an existing road southward in Doklam, a territory that is claimed by both China and Bhutan.[118][119][120][121][122][123] On 18 June 2017, as part of Operation Juniper,[124] about 270 armed Indian troops with two bulldozers crossed the Sikkim border into Doklam to stop the Chinese troops from constructing the road.[120][125][126] On 28 August, both India and China announced that they had withdrawn all their troops from the face-off site in Doklam.

Cambodia

[edit]Anti-government protests were ongoing in Cambodia from July 2013 to July 2014. Popular demonstrations in Phnom Penh took place against the government of Prime Minister Hun Sen, triggered by widespread allegations of electoral fraud during the Cambodian general election of 2013.[127] Demands to raise the minimum wage to $160 a month[128] and resentment at Vietnamese influence in Cambodia have also contributed to the protests.[129] The main opposition party refused to participate in parliament after the elections,[130] and major demonstrations took place throughout December 2013.[131] A government crackdown in January 2014 led to the deaths of 4 people and the clearing of the main protest camp.[132]

China

[edit]Xi Jinping succeeded Hu Jintao as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party and became the paramount leader of China on November 15, 2012. He immediately began an anti-corruption campaign, in which more than 100,000 individuals were indicted, including senior leader Zhou Yongkang.[133] There have been claims of political motives behind the campaign.[134]

In Xi's foreign policy, China became more aggressive with its actions in the South China Sea dispute, by building artificial islands and militarizing existing reefs, beginning in 2012.[135] Another key part of its foreign policy has been the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a strategy adopted by China involving infrastructure development and investments in countries and organizations in Asia, Europe, Africa, the Middle East, and the Americas.[136][137][138][139] China has signed cooperational documents on the belt and road initiative with 126 countries and 29 international organisations,[140] where various efforts then went ahead on infrastructure.[141]

In 2018, China's National People's Congress approves a constitutional change that removes term limits for its leaders, granting Xi Jinping the status of "leader for life".[142]

In the end of the decade, concerns started to grow about the future of the Chinese economy.[143] These concerns included whether the United States and China could positively resolve their disputes over trade.[144][145]

Hong Kong

[edit]The 2019–20 Hong Kong protests, also known as the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill (Anti-ELAB) movement, is an ongoing series of demonstrations in Hong Kong triggered by the introduction of the Fugitive Offenders amendment bill by the Hong Kong government.[146] If enacted, the bill would have empowered local authorities to detain and extradite criminal fugitives who are wanted in territories with which Hong Kong does not currently have extradition agreements, including Taiwan and mainland China. This led to concerns that the bill would subject Hong Kong residents and visitors to the jurisdiction and legal system of mainland China, which would undermine the region's autonomy and Hong Kong people's civil liberties. As the protests progressed, the protesters laid out five key demands, which were the withdrawal of the bill, investigation into alleged police brutality and misconduct, the release of arrested protesters, a complete retraction of the official characterisation of the protests as "riots", and Chief Executive Carrie Lam's resignation along with the introduction of universal suffrage for election of the Legislative Council and the Chief Executive.[147] [148] [149] [150] [151] [152] [153] [154] [155] [156]

India

[edit]Manmohan Singh's second ministry government faced a number of corruption charges over the organisation of the 2010 Commonwealth Games, the 2G spectrum allocation case and the allocation of coal blocks. After his term ended in 2014 he opted out from the race for the office of the Prime Minister of India during the 2014 Indian general election.[157] Modi led the BJP in the 2014 general election which gave the party a majority in the lower house of Indian parliament, the Lok Sabha, the first time for any single party since 1984. Under Modi's tenure, India has experienced democratic backsliding.[158][159][b] Following his party's victory in the 2019 general election, his administration revoked the special status of Jammu and Kashmir, introduced the Citizenship Amendment Act and three controversial farm laws, which prompted widespread protests and sit-ins across the country, resulting in a formal repeal of the latter. Described as engineering a political realignment towards right-wing politics, Modi became a figure of controversy domestically and internationally over his Hindu nationalist beliefs and his handling of the 2002 Gujarat riots, cited as evidence of an exclusionary social agenda.[c]

Iraq

[edit]

A series of demonstrations, marches, sit-ins and civil disobedience took place in Iraq from 2019 until 2021. It started on 1 October 2019, a date which was set by civil activists on social media, spreading mainly over the central and southern provinces of Iraq, to protest corruption, high unemployment, political sectarianism, inefficient public services and foreign interventionism. Protests spread quickly, coordinated over social media, to other provinces in Iraq. As the intensity of the demonstrations peaked in late October, protesters' anger focused not only on the desire for a complete overhaul of the Iraqi government but also on driving out Iranian influence, including Iranian-aligned Shia militias. The government, with the help of Iranian-backed militias responded brutally using live bullets, marksmen, hot water, hot pepper gas and tear gas against protesters, leading to many deaths and injuries.[173][174][175][176]

The protesters called for the end of the muhasasa system, existing since the first post-Saddam sovereign Iraqi government in 2006, in which government positions are being parceled out to the (presumed) ethnic or sectarian communities in Iraq like Shia, Sunni and Kurds, based on their presumed size, purportedly leading to incompetent and corrupt politics.[177][178][179] The protests, which were the largest of their kind in Iraq since the 2003 American invasion, became known within Iraq as the October Revolution (Arabic: ثورة تشرين, romanized: Thawrat Tishrīn), and gave rise to the October Protest Movement.[180]Kazakhstan

[edit]Nursultan Nazarbayev was given the title Elbasy (meaning "Leader of the Nation")[181] on 14 June 2010.[182] In the same year, he announced reforms to encourage a multi-party system in an attempt to counter the ruling Nur Otan's one-party control of the lower house Mazhilis from 2007. This led to the reinstatement of various parties in Parliament following the 2012 legislative elections, although having little influence and opposition as the parties supported and voted with the government while Nur Otan still had dominant-party control of the Mazhilis.

The Zhanaozen massacre took place in Kazakhstan's western Mangystau Region over the weekend of 16–17 December 2011. At least 14 protestors were killed by police in the oil town of Zhanaozen as they clashed with police on the country's Independence Day,[183] with unrest spreading to other towns in the oil-rich oblys, or region.[184]

In 2015, Nazarbayev was re-elected for the last time for a fifth term with almost 98% of the vote while in a middle of an economic crisis, as he ran virtually unopposed. In January 2017, Nazarbayev proposed constitutional reforms that would delegate powers to the Parliament of Kazakhstan. In May 2018, the Parliament approved a constitutional amendment allowing Nazarbayev to lead the Security Council for life.

In March 2019, Nazarbayev resigned from the presidency amid anti-government protests and was succeeded by Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, a close ally of Nazarbayev, who overwhelmingly won the following snap presidential elections in June 2019.

Myanmar

[edit]The 2011–2015 Myanmar political reforms were a series of political, economic and administrative reforms in Myanmar undertaken by the military-backed government. These reforms include the release of pro-democracy leader Aung San Suu Kyi from house arrest and subsequent dialogues with her, establishment of the National Human Rights Commission, general amnesties of more than 200 political prisoners, institution of new labour laws that allow labour unions and strikes, relaxation of press censorship, and regulations of currency practices.[185] As a consequence of the reforms, ASEAN has approved Myanmar's bid for the chairmanship in 2014.

Aung San Suu Kyi's party, the National League for Democracy, participated in by-elections held on 1 April 2012 after the government abolished laws that led to the NLD's boycott of the 2010 general election. She led the NLD in winning the by-elections in a landslide, winning 41 out of 44 of the contested seats, with Aung San Suu Kyi herself winning a seat representing Kawhmu Constituency in the lower house of the Myanmar Parliament. General elections were held on 8 November 2015, with the National League for Democracy winning a supermajority of seats in the combined national parliament.[186]

Before the elections, Aung San Suu Kyi announced that even though she was constitutionally barred from the presidency, she would hold the real power in any NLD-led government.[187] On 30 March 2016 she became Minister for the President's Office, for Foreign Affairs, for Education and for Electric Power and Energy in President Htin Kyaw's government; later she relinquished the latter two ministries and President Htin Kyaw appointed her State Counsellor, a position akin to a Prime Minister created especially for her.[188][189][190]

In late 2016, Myanmar's armed forces and police started a major crackdown on the people in Rakhine State in the country's northwestern region. The Burmese military were accused of ethnic cleansing and genocide by various United Nations agencies, International Criminal Court officials, human rights groups, journalists, and governments.[191][192][193] A study estimated in January 2018 that the military and local Rakhine population killed at least 25,000 Rohingya people and perpetrated gang rapes and other forms of sexual violence against 18,000 Rohingya women and girls.[194][195][196] The military operations displaced a large number of people, and created a refugee crisis, which resulted in the largest human exodus in Asia since the Vietnam War.[197]

Middle East

[edit]The Arab Spring was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings, and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began in response to corruption and economic stagnation and was influenced by the Tunisian Revolution.[198][199] From Tunisia, the protests then spread to five other countries: Libya, Egypt, Yemen, Syria, and Bahrain, where either the ruler was deposed (Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Muammar Gaddafi, Hosni Mubarak, and Ali Abdullah Saleh) or major uprisings and social violence occurred including riots, civil wars, or insurgencies. Sustained street demonstrations took place in Morocco, Iraq, Algeria, Iranian Khuzestan,[citation needed] Lebanon, Jordan, Kuwait, Oman, and Sudan. Minor protests took place in Djibouti, Mauritania, Palestine, Saudi Arabia, and the Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara.[200] A major slogan of the demonstrators in the Arab world is ash-shaʻb yurīd isqāṭ an-niẓām! ("the people want to bring down the regime").

The wave of initial revolutions and protests faded by mid-2012, as many Arab Spring demonstrations met with violent responses from authorities, as well as from pro-government militias, counter-demonstrators, and militaries. These attacks were answered with violence from protesters in some cases. Large-scale conflicts resulted: the Syrian Civil War;[201][202] the rise of ISIL, insurgency in Iraq and the following civil war;[203] the Egyptian Crisis, coup, and subsequent unrest and insurgency;[204] the Libyan Civil War; and the Yemeni Crisis and following civil war.[205] Regimes that lacked major oil wealth and hereditary succession arrangements were more likely to undergo regime change.[206]

Some have referred to the succeeding and still ongoing conflicts as the Arab Winter.[201][202][203][204][205] As of May 2018, only the uprising in Tunisia has resulted in a transition to constitutional democratic governance.[200] Recent uprisings in Sudan and Algeria show that the conditions that started the Arab Spring have not faded and political movements against authoritarianism and exploitation are still occurring.[207] In 2019, multiple uprisings and protest movements in Algeria, Sudan, Iraq, Lebanon, and Egypt have been seen as a continuation of the Arab Spring.[208][209]

Europe

[edit]Debt crisis and political fallout

[edit]

| Part of a series on the |

| Great Recession |

|---|

| Timeline |

The euro area crisis, often also referred to as the eurozone crisis, European debt crisis or European sovereign debt crisis, was a multi-year debt and financial crisis that took place in the European Union (EU) from 2009 until the mid to late 2010s. Several eurozone member states (Greece, Portugal, Ireland and Cyprus) were unable to repay or refinance their government debt or to bail out fragile banks under their national supervision without the assistance of other eurozone countries, the European Central Bank (ECB), or the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The euro area crisis was caused by a sudden stop of the flow of foreign capital into countries that had substantial current account deficits and were dependent on foreign lending. The crisis was worsened by the inability of states to resort to devaluation (reductions in the value of the national currency) due to having the Euro as a shared currency.[212][213] Debt accumulation in some eurozone members was in part due to macroeconomic differences among eurozone member states prior to the adoption of the euro. It also involved a process of cross-border financial contagion. The European Central Bank adopted an interest rate that incentivized investors in Northern eurozone members to lend to the South, whereas the South was incentivized to borrow because interest rates were very low. Over time, this led to the accumulation of deficits in the South, primarily by private economic actors.[212][213] A lack of fiscal policy coordination among eurozone member states contributed to imbalanced capital flows in the eurozone,[212][213] while a lack of financial regulatory centralization or harmonization among eurozone states, coupled with a lack of credible commitments to provide bailouts to banks, incentivized risky financial transactions by banks.[212][213] The detailed causes of the crisis varied from country to country. In several countries, private debts arising from a property bubble were transferred to sovereign debt as a result of banking system bailouts and government responses to slowing economies post-bubble. European banks own a significant amount of sovereign debt, such that concerns regarding the solvency of banking systems or sovereigns are negatively reinforcing.[214]

The onset of crisis was in late 2009 when the Greek government disclosed that its budget deficits were far higher than previously thought.[212] Greece called for external help in early 2010, receiving an EU–IMF bailout package in May 2010.[212] European nations implemented a series of financial support measures such as the European Financial Stability Facility (EFSF) in early 2010 and the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) in late 2010. The ECB also contributed to solve the crisis by lowering interest rates and providing cheap loans of more than one trillion euro in order to maintain money flows between European banks. On 6 September 2012, the ECB calmed financial markets by announcing free unlimited support for all eurozone countries involved in a sovereign state bailout/precautionary programme from EFSF/ESM, through some yield lowering Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT).[215] Ireland and Portugal received EU-IMF bailouts In November 2010 and May 2011, respectively.[212] In March 2012, Greece received its second bailout. Both Cyprus received rescue packages in June 2012.[212]

Return to economic growth and improved structural deficits enabled Ireland and Portugal to exit their bailout programmes in July 2014. Greece and Cyprus both managed to partly regain market access in 2014. Spain never officially received a bailout programme. Its rescue package from the ESM was earmarked for a bank recapitalisation fund and did not include financial support for the government itself. The crisis had significant adverse economic effects and labour market effects, with unemployment rates in Greece and Spain reaching 27%,[216] and was blamed for subdued economic growth, not only for the entire eurozone but for the entire European Union. The austerity policies implemented as a result of the crisis also produced a sharp rise in poverty levels and a significant increase in income inequality across Southern Europe.[217] It had a major political impact on the ruling governments in 10 out of 19 eurozone countries, contributing to power shifts in Greece, Ireland, France, Italy, Portugal, Spain, Slovenia, Slovakia, Belgium, and the Netherlands as well as outside of the eurozone in the United Kingdom.[218]Effects on governments

[edit]

The handling of the European debt crisis led to the premature end of several European national governments and influenced the outcome of many elections:

- Ireland – February 2011 – After a high deficit in the government's budget in 2010 and the uncertainty surrounding the proposed bailout from the International Monetary Fund, the 30th Dáil (parliament) collapsed the following year, which led to a subsequent general election, collapse of the preceding government parties, Fianna Fáil and the Green Party, the resignation of the Taoiseach Brian Cowen and the rise of the Fine Gael party, which formed a government alongside the Labour Party in the 31st Dáil, which led to a change of government and the appointment of Enda Kenny as Taoiseach.

- Portugal – March 2011 – Following the failure of parliament to adopt the government austerity measures, PM José Sócrates and his government resigned, bringing about early elections in June 2011.[219][220]

- Finland – April 2011 – The approach to the Portuguese bailout and the EFSF dominated the April 2011 election debate and formation of the subsequent government.[221][222]

- Spain – July 2011 – Following the failure of the Spanish government to handle the economic situation, PM José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero announced early elections in November.[223] "It is convenient to hold elections this fall so a new government can take charge of the economy in 2012, fresh from the balloting," he said.[224] Following the elections, Mariano Rajoy became PM.

- Slovenia – September 2011 – Following the failure of June referendums on measures to combat the economic crisis and the departure of coalition partners, the Borut Pahor government lost a motion of confidence and December 2011 early elections were set, following which Janez Janša became PM.[225] After a year of rigorous saving measures, and also due to continuous opening of ideological question, the centre-right government of Janez Janša was ousted on 27 February 2013 by nomination of Alenka Bratušek as the PM-designated of a new centre-left coalition government.[226]

- Slovakia – October 2011 – In return for the approval of the EFSF by her coalition partners, PM Iveta Radičová had to concede early elections in March 2012, following which Robert Fico became PM.

- Italy – November 2011 – Following market pressure on government bond prices in response to concerns about levels of debt, the right-wing cabinet, of the long-time Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi, lost its majority: Berlusconi resigned on 12 November and four days later was replaced by the technocratic government of Mario Monti.[227]

- Greece – November 2011 – After intense criticism from within his own party, the opposition and other EU governments, for his proposal to hold a referendum on the austerity and bailout measures, PM George Papandreou of the PASOK party announced his resignation in favour of a national unity government between three parties, of which only two currently remain in the coalition.[228] Following the vote in the Greek parliament on the austerity and bailout measures, which both leading parties supported but many MPs of these two parties voted against, Papandreou and Antonis Samaras expelled a total of 44 MPs from their respective parliamentary groups, leading to PASOK losing its parliamentary majority.[229] The early Greek legislative election, 2012 were the first time in the history of the country, at which the bipartisanship (consisted of PASOK and New Democracy parties), which ruled the country for over 40 years, collapsed in votes as a punishment for their support to the strict measures proposed by the country's foreign lenders and the Troika (consisted of the European Commission, the IMF and the European Central Bank). The popularity of PASOK dropped from 42.5% in 2010 to as low as 7% in some polls in 2012.[230] The radical right-wing, extreme left-wing, communist and populist political parties that have opposed the policy of strict measures, won the majority of the votes.

- Netherlands – April 2012 – After talks between the VVD, CDA and PVV over a new austerity package of about 14 billion euros failed, the Rutte cabinet collapsed. Early elections were called for 12 September 2012. To prevent fines from the EU – a new budget was demanded by 30 April – five different parties called the Kunduz coalition forged together an emergency budget for 2013 in just two days.[231]

- France – May 2012 – The 2012 French presidential election became the first time since 1981 that an incumbent failed to gain a second term, when Nicolas Sarkozy lost to François Hollande.

Terrorism

[edit]There was a rise in Islamic terrorist incidents in Europe after 2014.[232][233][234] The years 2014–16 saw more people killed by Islamic terrorist attacks in Europe than all previous years combined, and the highest rate of attack plots per year.[235] Most of this terrorist activity was inspired by the Islamic State,[235][236] and many European states have had some involvement in the military intervention against it. A number of plots involved people who entered or re-entered Europe as asylum seekers during the European migrant crisis,[236][237][238] and some attackers had returned to Europe after fighting in the Syrian Civil War.[236] The Jewish Museum of Belgium shooting in May 2014 was the first attack in Europe by a returnee from the Syrian war.[239] The deadliest attacks of this period have been the November 2015 Paris attacks (130 killed), the July 2016 Nice truck attack (86 killed), the June 2016 Atatürk Airport attack (45 killed), the March 2016 Brussels bombings (32 killed), and the May 2017 Manchester Arena bombing (22 killed). These attacks and threats have led to major security operations and plans such as Opération Sentinelle in France, Operation Vigilant Guardian and the Brussels lockdown in Belgium, and Operation Temperer in the United Kingdom.

Migrant crisis

[edit]Europe began registering increased numbers of refugee arrivals in 2010 due to a confluence of conflicts in parts of the Middle East, Asia and Africa, particularly the wars in Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan, but also terrorist insurgencies in Nigeria and Pakistan, and long-running human rights abuses in Eritrea, all contributing to refugee flows.[240] Many millions initially sought refuge in comparatively stable countries near their origin, but while these countries were largely free of war, living conditions for refugees were often very poor. In Turkey, many were not permitted to work; in Jordan and Lebanon which hosted millions of Syrian refugees,[241] large numbers were confined to squalid refugee camps.[240][242] As it became clear that the wars in their home countries would not end in the foreseeable future, many increasingly wished to settle permanently elsewhere. In addition, starting in 2014, Lebanon, Jordan and Egypt stopped accepting Syrian asylum seekers. Together these events caused a surge in people fleeing to Europe in 2015.[240]

Anti-establishment parties

[edit]Populist and far-right political parties proved very successful throughout Europe in the late-2010s. In Austria, Sebastian Kurz, chairman of the centre-right Austrian People's Party reached an agreement on a coalition with the far-right Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) in 2017. The 2017 French presidential election caused a radical shift in French politics, as the prevailing parties of The Republicans and Socialists failed to make it to the second round of voting, with far-right Marine Le Pen and political newcomer Emmanuel Macron instead facing each other.[243] In the 2018 Italian general election, no political group or party won an outright majority, resulting in a hung parliament.[244] In the election, the right-wing alliance, in which Matteo Salvini's populist League (LN) emerged as the main political force, won a plurality of seats in the Chamber of Deputies and in the Senate, while the anti-establishment Five Star Movement (M5S) led by Luigi Di Maio became the party with the largest number of votes.

North America

[edit]Following pressure from the US President Donald Trump, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was superseded by the new United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement (USMCA).[245]

Canada

[edit]The 40th Canadian Parliament was dissolved in March 2011, after a no-confidence vote that found Stephen Harper's government to be in contempt of Parliament. In the federal election, the Conservatives won a majority government. During his third term, Harper withdrew Canada from the Kyoto Protocol, launched Operation Impact in opposition to ISIL, repealed the long-gun registry, passed the Anti-terrorism Act, 2015, launched Canada's Global Markets Action Plan and grappled with controversies surrounding the Canadian Senate expenses scandal and the Robocall scandal.

In the 2015 federal election, the Conservative Party lost power to the Liberal Party led by Justin Trudeau, moving the third-placed Liberals from 36 seats to 184 seats, the largest-ever numerical increase by a party in a Canadian federal election. As Prime Minister, major government initiatives he undertook during his first term include legalizing recreational marijuana through the Cannabis Act; attempting Senate appointment reform by establishing the Independent Advisory Board for Senate Appointments and establishing the federal carbon tax; while grappling with ethics investigations concerning the Aga Khan affair and later, the SNC-Lavalin affair.

Caribbean

[edit]The Netherlands Antilles as an autonomous Caribbean country within the Kingdom of the Netherlands was dissolved on 10 October 2010.[246][247] After dissolution, the "BES islands" of the Dutch Caribbean—Bonaire, Sint Eustatius, and Saba—became the Caribbean Netherlands, "special municipalities" of the Netherlands proper—a structure that only exists in the Caribbean. Meanwhile Curaçao and Sint Maarten became constituent countries within the Kingdom of the Netherlands, along the lines of Aruba, which separated from the Netherlands Antilles in 1986.

General elections were held in Barbados on 24 May 2018.[248] The result was a landslide victory for the opposition Barbados Labour Party (BLP), which won all 30 seats in the House of Assembly,[249] resulting in BLP leader Mia Mottley becoming the country's first female Prime Minister. The BLP's victory was the first time a party had won every seat in the House of Assembly. The ruling Democratic Labour Party (DLP) led by Freundel Stuart lost all 16 seats,[249] the worst defeat of a sitting government in Barbadian history. The DLP saw its vote share more than halve compared to the previous elections in 2013, with only one of its candidates receiving more than 40 percent of the vote. Stuart was defeated in his own constituency, receiving only 26.7 percent of the vote,[250] the second time a sitting Prime Minister had lost their own seat. The election was fought primarily on the DLP's stewardship of the economy during its decade in power. The government had had to contend with numerous downgrades of its credit rating due to fallout from the global financial crisis. The BLP criticised the DLP over rising taxes and a declining standard of living, and promised numerous infrastructure upgrades if elected.[250]

Cuba

[edit]The 6th Congress of the Communist Party of Cuba, the governing political party of Cuba, took place on April 16 – 19, 2011,[251] in Havana at the Palacio de las Convenciones.[252] The main focus of the congress was to introduce economic, social, and political reforms in order to modernize the country's socialist system. The Congress also elected Raúl Castro as First Secretary, the position vacant since Fidel Castro's stepping down in 2006.[253]

On December 17, 2014, U.S. President Barack Obama and Cuban leader Raúl Castro announced the beginning of the process of normalizing relations between Cuba and the United States. The normalization agreement was secretly negotiated in preceding months, facilitated by Pope Francis and largely hosted by the Government of Canada. Meetings were held in both Canada and Vatican City.[254] The agreement would see the lifting of some U.S. travel restrictions, fewer restrictions on remittances, U.S. banks' access to the Cuban financial system,[255] and the reopening of the U.S. embassy in Havana and the Cuban embassy in Washington, which both closed in 1961 after the breakup of diplomatic relations as a result of Cuba's close alliance with the USSR.[256][257]

90-year old former First Secretary of the Communist Party of Cuba and President of the Council of State, Fidel Castro died of natural causes at 22:29 (CST) in the evening of 25 November 2016. The Council of State of the Republic of Cuba declared nine days of national mourning from 06:00 on 26 November until 12:00 on 4 December. A statement read: "During the mourning period, all public events and activities will cease, the national flag will fly at half-mast on public buildings and at military facilities and television and radio will broadcast informative, patriotic and historical programmes."[258][259]

A constitutional referendum was held in Cuba on 24 February 2019.[260] Voters were asked whether they approved of a new constitution passed by the National Assembly of People's Power in July 2018.[261] The reforms were approved, with 90.61% of valid votes cast in favour. The new constitution came into force on 10 April 2019 after it was proclaimed in the Cuban National Assembly and published in the Official Gazette of the Republic.[262] The referendum recognized both private property and foreign direct investment, among other things, such as removing obstacles to same-sex marriage and banning discrimination based on gender, race, ethnic origin, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability, the introduction of habeas corpus and restoration of a presumption of innocence in the justice system which was last provided for in the 1940 Constitution of Cuba, and other political reforms, such as presidential term and age limits, as checks on government power.[263] The new constitution also omits the aim of building a communist society and instead works towards the construction of socialism.[264]

Haiti

[edit]Due to the January 2010 earthquake, Haitian presidential election was indefinitely postponed;[265] although November 28 was then decided as the date to hold the presidential and legislative elections. Following the magnitude 7.0 earthquake, there were concerns of instability in the country, and the election came amid international pressure over instability in the country.[266] Some questioned whether Haiti was ready to hold an election following the earthquake that left more than a million people in makeshift camps and without IDs. There was also a fear that the election could throw the country into a political crisis due to a lack of transparency and voting fraud.[267] The United Nations voted to extend MINUSTAH's mandate amid fears of instability.

Amid allegations of fraud in the 2015 elections, Michel Martelly resigned the presidency on 10 February 2016, leaving Haiti without a president for a week. The National Assembly elected on 17 February 2016 Jocelerme Privert as provisional President.[268][269] Privert formed a month-long verification commission to restore legitimacy to the electoral process. In May 2016, the commission audited about 13,000 ballots and determined that the elections had been dishonest and recommended a complete rerun of the election.[270][271]

Protests began in cities throughout Haiti on 7 July 2018 in response to increased fuel prices. Over time, these protests evolved into demands for the resignation of the president. Led by opposition politician Jean-Charles Moïse (no relation), protesters stated that their goal was to create a transitional government, provide social programs, and prosecute allegedly corrupt officials. Hundreds of thousands took part in weekly protests calling for the government to resign.[272][273][274][275][276]

Mexico

[edit]Felipe Calderón Hinojosa became the 56th president of Mexico (and the second from the conservative National Action Party) after a controversial election in 2006. He quickly declared a War on Drugs that ended up costing about 200,000 lives over the next ten years.[277] Calderon's drug war, which cost 47,000 lives during the last two years of his presidency (the balance), became the most important issue during the 2012 Mexican general election. The election was won by the former Governor of the State of Mexico Enrique Peña Nieto of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the political party that had dominated Mexican politics during most of the 20th century.

Peña Nieto continued the drug war with no better success than Calderon had had. Low points were the September 26, 2014 Ayotzinapa (Iguala) mass kidnapping of 43 students enrolled in a teachers' college in the southern state of Guerrero,[278][279] and the 2015 prison escape of notorious drug-dealer Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán. Peña Nieto was also personally wrapped up in a corruption scandal involving a US$7 million (MXN $100 million) house known as La Casa Blanca ("The White House") purchased by his showcase wife, actress Angélica Rivera. This was just one of many scandals that rocked his administration.[280] By the time he left office in 2018 he had an 18% approval and a 77% disapproval rating, making him one of the least popular presidents in Mexican history.[281]

Andrés Manuel López Obrador (commonly called "AMLO") was a candidate for president for the third time in the 2018 Mexican general election, representing the Juntos Haremos Historia ("Together we will make history"), coalition. He won with 53% of the vote. AMLO ended the drug war and established a National Guard, but violence continued to plague the nation:.[282] It was reported that 2019 was the most violent year in Mexican history, with 29,574 homicides and femicides registered during the first ten months of the year.[283] AMLO has run an austere government, cracking down on corruption, reducing government salaries (including his own), and selling off properties seized during drug raids as well as government vehicles, including the presidential plane.[283]

United States

[edit]

The Affordable Care Act (ACA), formally known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA) and informally as Obamacare, is a landmark U.S. federal statute enacted by the 111th United States Congress and signed into law by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010. Together with the Health Care and Education Reconciliation Act of 2010 amendment, it represents the U.S. healthcare system's most significant regulatory overhaul and expansion of coverage since the enactment of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965.[284][285][286][287] Most of the act's provisions are still in effect.

The ACA's major provisions came into force in 2014. By 2016, the uninsured share of the population had roughly halved, with estimates ranging from 20 to 24 million additional people covered.[288][289] The law also enacted a host of delivery system reforms intended to constrain healthcare costs and improve quality. After it went into effect, increases in overall healthcare spending slowed, including premiums for employer-based insurance plans.[290]

The increased coverage was due, roughly equally, to an expansion of Medicaid eligibility and to changes to individual insurance markets. Both received new spending, funded through a combination of new taxes and cuts to Medicare provider rates and Medicare Advantage. Several Congressional Budget Office (CBO) reports said that overall these provisions reduced the budget deficit, that repealing ACA would increase the deficit,[291][292] and that the law reduced income inequality by taxing primarily the top 1% to fund roughly $600 in benefits on average to families in the bottom 40% of the income distribution.[293]

The act largely retained the existing structure of Medicare, Medicaid, and the employer market, but individual markets were radically overhauled.[284][294] Insurers were made to accept all applicants without charging based on preexisting conditions or demographic status (except age). To combat the resultant adverse selection, the act mandated that individuals buy insurance (or pay a monetary penalty) and that insurers cover a list of "essential health benefits".

Before and after enactment the ACA faced strong political opposition, calls for repeal and legal challenges. In National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court ruled that states could choose not to participate in the law's Medicaid expansion, but upheld the law as a whole.[295] The federal health insurance exchange, HealthCare.gov, faced major technical problems at the beginning of its rollout in 2013. Polls initially found that a plurality of Americans opposed the act, although its individual provisions were generally more popular.[296] By 2017, the law had majority support.[297] The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 set the individual mandate penalty at $0 starting in 2019 due to its overall unpopularity and to reduce the federal budget deficit.[298][299]

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

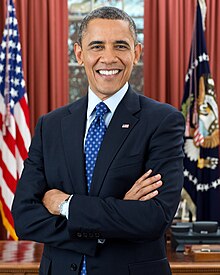

Personal

Illinois State Senator and U.S. Senator from Illinois 44th President of the United States

Tenure

|

||

In 2011, ongoing political debate in the United States Congress about the appropriate level of government spending and its effect on the national debt and deficit reached a crisis centered on raising the debt ceiling, leading to the passage of the Budget Control Act of 2011.

The Republican Party, which gained control of the House of Representatives in January 2011, demanded that President Obama negotiate over deficit reduction in exchange for an increase in the debt ceiling, the statutory maximum of money the Treasury is allowed to borrow. The debt ceiling had routinely been raised in the past without partisan debate or additional terms or conditions. This reflects the fact that the debt ceiling does not prescribe the amount of spending, but only ensures that the government can pay for the spending to which it has already committed itself. Some use the analogy of an individual "paying their bills."

If the United States breached its debt ceiling and were unable to resort to other "extraordinary measures", the Treasury would have to either default on payments to bondholders or immediately curtail payment of funds owed to various companies and individuals that had been mandated but not fully funded by Congress. Both situations would likely have led to a significant international financial crisis.

On July 31, two days prior to when the Treasury estimated the borrowing authority of the United States would be exhausted, Republicans agreed to raise the debt ceiling in exchange for a complex deal of significant future spending cuts. The crisis did not permanently resolve the potential of future use of the debt ceiling in budgetary disputes, as shown by the subsequent crisis in 2013.

The crisis sparked the most volatile week for financial markets since the 2007–2008 financial crisis, with the stock market trending significantly downward. Prices of government bonds ("Treasuries") rose as investors, anxious over the dismal prospects of the US economic future and the ongoing European sovereign-debt crisis, fled into the still-perceived relative safety of US government bonds. Later that week, the credit-rating agency Standard & Poor's downgraded the credit rating of the United States government for the first time in the country's history, though the other two major credit-rating agencies, Moody's and Fitch, retained America's credit rating at AAA. The Government Accountability Office (GAO) estimated that the delay in raising the debt ceiling increased government borrowing costs by $1.3 billion in 2011 and also pointed to unestimated higher costs in later years.[300] The Bipartisan Policy Center extended the GAO's estimates and found that delays in raising the debt ceiling would raise borrowing costs by $18.9 billion.[301]

Barack Obama's tenure as the 44th president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2009, and ended on January 20, 2017. Obama, a Democrat from Illinois, took office following his victory over Republican nominee John McCain in the 2008 presidential election. Four years later, in the 2012 presidential election, he defeated Republican nominee Mitt Romney, to win re-election. Obama is the first African American president, the first multiracial president, the first non-white president,[d] and the first president born in Hawaii. Obama was succeeded by Republican Donald Trump, who won the 2016 presidential election. Historians and political scientists rank him among the upper tier in historical rankings of American presidents.

Obama's accomplishments during the first 100 days of his presidency included signing the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009 relaxing the statute of limitations for equal-pay lawsuits;[303] signing into law the expanded Children's Health Insurance Program (S-CHIP); winning approval of a congressional budget resolution that put Congress on record as dedicated to dealing with major health care reform legislation in 2009; implementing new ethics guidelines designed to significantly curtail the influence of lobbyists on the executive branch; breaking from the Bush administration on a number of policy fronts, except for Iraq, in which he followed through on Bush's Iraq withdrawal of US troops;[304] supporting the UN declaration on sexual orientation and gender identity; and lifting the 7½-year ban on federal funding for embryonic stem cell research.[305] Obama also ordered the closure of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp, in Cuba, though it remains open. He lifted some travel and money restrictions to the island.[304]

Obama signed many landmark bills into law during his first two years in office. The main reforms include: the Affordable Care Act, sometimes referred to as "the ACA" or "Obamacare", the Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, and the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010. The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act served as economic stimuli amidst the Great Recession. After a lengthy debate over the national debt limit, he signed the Budget Control Act of 2011 and the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012. In foreign policy, he increased US troop levels in Afghanistan, reduced nuclear weapons with the United States–Russia New START treaty, and ended military involvement in the Iraq War. He gained widespread praise for ordering Operation Neptune Spear, the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, who was responsible for the September 11 attacks. In 2011, Obama ordered the drone-strike killing in Yemen of al-Qaeda operative Anwar al-Awlaki, who was an American citizen. He ordered military involvement in Libya in order to implement UN Security Council Resolution 1973, contributing to the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi.

After winning re-election by defeating Republican opponent Mitt Romney, Obama was sworn in for a second term on January 20, 2013. During this term, he condemned the 2013 Snowden leaks as unpatriotic, but called for more restrictions on the National Security Agency (NSA) to address privacy issues. Obama also promoted inclusion for LGBT Americans. His administration filed briefs that urged the Supreme Court to strike down same-sex marriage bans as unconstitutional (United States v. Windsor and Obergefell v. Hodges); same-sex marriage was legalized nationwide in 2015 after the Court ruled so in Obergefell. He advocated for gun control in response to the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, indicating support for a ban on assault weapons, and issued wide-ranging executive actions concerning global warming and immigration. In foreign policy, he ordered military interventions in Iraq and Syria in response to gains made by ISIL after the 2011 withdrawal from Iraq, promoted discussions that led to the 2015 Paris Agreement on global climate change, drew down US troops in Afghanistan in 2016, initiated sanctions against Russia following its annexation of Crimea and again after interference in the 2016 US elections, brokered the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action nuclear deal with Iran, and normalized US relations with Cuba. Obama nominated three justices to the Supreme Court: Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan were confirmed as justices, while Merrick Garland was denied hearings or a vote from the Republican-majority Senate.

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Business and personal 45th & 47th President of the United States Tenure

Impeachments Civil and criminal prosecutions  |

||

The first tenure of Donald Trump as the president of the United States began on January 20, 2017, when Trump was inaugurated as the 45th president, and ended on January 20, 2021. Trump, a Republican from New York, took office following his electoral college victory over Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton in the 2016 presidential election. Upon his inauguration, he became the first president in American history without prior public office or military background. Trump made an unprecedented number of false or misleading statements during his 2016 campaign and first presidency. His first presidency ended following his defeat in the 2020 presidential election to former Democratic vice president Joe Biden, after his first term in office.

Trump was unsuccessful in his efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act but rescinded the individual mandate. He sought substantial spending cuts to major welfare programs, including Medicare and Medicaid. Trump signed the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and a partial repeal of the Dodd–Frank Act. He appointed Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Coney Barrett to the Supreme Court. Trump reversed numerous environmental regulations, withdrew from the Paris Agreement on climate change, and signed the Great American Outdoors Act but later issued an Executive Order undercutting its impact. He signed the First Step Act aimed at reforming federal prisons. He enacted tariffs, triggering retaliatory tariffs from China, Canada, Mexico, and the European Union. He withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations and signed the United States–Mexico–Canada Agreement, a successor to the North American Free Trade Agreement with modest changes. The federal deficit significantly increased under Trump due to spending increases and tax cuts.

Trump implemented a controversial family separation policy for migrants apprehended at the United States–Mexico border, starting in 2018. His demand for the federal funding of a border wall resulted in the longest US government shutdown in history. He deployed federal law enforcement forces in response to the racial unrest in 2020. Trump's "America First" foreign policy was characterized by unilateral actions, disregarding traditional norms and allies. His administration implemented a major arms sale to Saudi Arabia; denied citizens from several Muslim-majority countries entry into the United States; recognized Jerusalem as the capital of Israel; and brokered the Abraham Accords, a series of normalization agreements between Israel and various Arab states. Trump withdrew United States troops from northern Syria, allowing Turkey to occupy the area. His administration made a conditional deal with the Taliban to withdraw United States troops from Afghanistan in 2021. Trump met North Korea's leader Kim Jong Un three times. He withdrew the United States from the Iran nuclear agreement and later escalated tensions in the Persian Gulf by ordering the assassination of General Qasem Soleimani.

Robert Mueller's Special Counsel investigation (2017–2019) concluded that Russia interfered to favor Trump's candidacy and that while the prevailing evidence "did not establish that members of the Trump campaign conspired or coordinated with the Russian government", possible obstructions of justice occurred during the course of that investigation. Trump attempted to pressure Ukraine to announce investigations into his political rival Joe Biden, triggering his first impeachment by the House of Representatives on December 18, 2019, but he was acquitted by the Senate on February 5, 2020. Trump reacted slowly to the COVID-19 pandemic, ignored or contradicted many recommendations from health officials in his messaging, and promoted misinformation about unproven treatments and the availability of testing.

Following his loss in the 2020 presidential election to Biden, Trump made unproven claims of widespread electoral fraud and initiated an extensive campaign to overturn the results. At a rally on January 6, 2021, Trump urged his supporters to march to the Capitol, where the electoral votes were being counted by Congress in order to formalize Biden's victory. A mob of Trump supporters stormed the Capitol, suspending the count and causing Vice President Mike Pence and other members of Congress to be evacuated. On January 13, the House voted to impeach Trump an unprecedented second time for incitement of insurrection, but he was later acquitted by the Senate again on February 13, after he had already left office.

Trump was elected for a second non-consecutive term in 2024 and will start his second presidency as the 47th president on January 20, 2025.

South America

[edit] |

|

| Map of Latin America showing countries with centre-left, left-wing or socialist governments (red) and centre-right, right-wing or conservative governments (blue) in 2011 (left) and 2018 (right). | |

The Conservative wave brought many right-wing politicians to power across the continent. In Argentina the Peronist president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner was replaced by the conservative-liberal Mauricio Macri in 2015; in Brazil, Dilma Rousseff's impeachment resulted in the rise of her Vice President Michel Temer to power in 2016; in Chile the conservative Sebastián Piñera followed the socialist Michelle Bachelet in 2017; and in 2018 the far-right congressman Jair Bolsonaro became 38th president of Brazil.[306]