Big Brother (Nineteen Eighty-Four)

| Big Brother | |

|---|---|

| |

| First appearance | Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) |

| Created by | George Orwell |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Male |

| Occupation | Leader of Oceania |

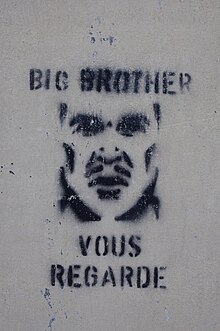

Big Brother is a character and symbol in George Orwell's dystopian 1949 novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. He is ostensibly the leader of Oceania, a totalitarian state wherein the ruling party, Ingsoc, wields total power "for its own sake" over the inhabitants. In the society that Orwell describes, every citizen is under constant surveillance by the authorities, mainly by telescreens (with the exception of the Proles). The people are constantly reminded of this by the slogan "Big Brother is watching you": a maxim that is ubiquitously on display throughout the novel.

In modern culture, the term "Big Brother" has entered the lexicon as a synecdoche for abuse of government power, particularly in respect to civil liberties, often specifically related to mass surveillance and a lack of choice in society.[1]

Character origins[edit]

There are many theories about the origin of the character. In the essay section of his novel 1985, Anthony Burgess states that Orwell got the idea for the name of Big Brother from advertising billboards for educational correspondence courses from a company called Bennett's during World War II. The original posters showed J. M. Bennett himself, a kindly-looking old man offering guidance and support to would-be students with the phrase "Let me be your father." According to Burgess, after Bennett's death, his son took over the company and the posters were replaced with pictures of the son (who looked imposing and stern in contrast to his father's kindly demeanor) with the text "Let me be your big brother".[2]

Additional speculation from Douglas Kellner of the University of California, Los Angeles, argued that Big Brother represents Joseph Stalin, representing Stalinism, and Adolf Hitler, representing Nazism.[3][4] Another theory is that the inspiration for Big Brother was Brendan Bracken, the Minister of Information, a government department in wartime United Kingdom, until 1945. Orwell worked under Bracken on the BBC's Indian, Hong Kong and Malayan Service. Bracken was customarily referred to by his employees by his initials, B.B., the same initials as the character Big Brother. Orwell also resented the wartime censorship and need to manipulate information which he felt came from the highest levels of the Minister of Information and from Bracken's office in particular.

The idea of Big Brother could be also borrowed from the 1937 H. G. Wells novel Star Begotten, in which "Big Brother" is referenced as a fictitious example of "mystical personifications" able to easily manipulate the common man,[5] as well as the Soviet Union, where there was an ideology of 'brotherly nations' or 'brotherly countries'. Russia presented itself as a big brother who watches over its younger brothers (other nations). The ideological word 'big brother' or 'older brother' was very well known and used in the Soviet Republics before and after the Second World War.[6] In the "Circe" episode of James Joyce's Ulysses (1922) the prophet Elijah addresses God as "Big Brother up there, Mr President".[7]

Portrayal in the novel[edit]

Existence[edit]

In the novel, it is never explicitly indicated if Big Brother is or had been a real person, or is a fictional personification of the Party, similar to Britannia and Uncle Sam. Big Brother is described as appearing on posters and telescreens as a man in his mid-forties. In Party propaganda, Big Brother is presented as one of the founders of the Party.

At one point, Winston Smith, the protagonist of Orwell's novel, tries "to remember in what year he had first heard mention of Big Brother. He thought it must have been at some time in the sixties, but it was impossible to be certain. In the Party histories, Big Brother figured as the leader and guardian of the Revolution since its very earliest days. His exploits had been gradually pushed backwards in time until already they extended into the fabulous world of the forties and the thirties, when the capitalists in their strange cylindrical hats still rode through the streets of London".

In the fictional book The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, read by Winston Smith and purportedly written by political theorist Emmanuel Goldstein, Big Brother is referred to as infallible and all-powerful. No one has ever seen him and there is a reasonable certainty that he will never die. He is simply "the guise in which the Party chooses to exhibit itself to the world" since the emotions of love, fear and reverence are more easily focused on an individual (if only a face on the hoardings and a voice on the telescreens) than an organisation. When Winston Smith is later arrested, O'Brien repeats that Big Brother will never die. When Smith asks if Big Brother exists, O'Brien describes him as "the embodiment of the Party" and says that he will exist as long as the Party exists. When Winston asks "Does Big Brother exist the same way I do?" (meaning is Big Brother an actual human being), O'Brien replies "You do not exist" (meaning that Smith is now an unperson; an example of doublethink).

Cult of personality[edit]

Big Brother is the subject of a cult of personality. A spontaneous ritual of devotion to "BB" is illustrated at the end of the compulsory Two Minutes Hate:

At this moment the entire group of people broke into a deep, slow, rhythmic chant of 'B-B! ... B-B! ... B-B!'—over and over again, very slowly, with a long pause between the first 'B' and the second—a heavy murmurous sound, somehow curiously savage, in the background of which one seemed to hear the stamps of naked feet and the throbbing of tom-toms. For perhaps as much as thirty seconds they kept it up. It was a refrain that was often heard in moments of overwhelming emotion. Partly it was a sort of hymn to the wisdom and majesty of Big Brother, but still more it was an act of self-hypnosis, a deliberate drowning of consciousness by means of rhythmic noise.[8]

Though Oceania's Ministry of Truth, Ministry of Plenty and Ministry of Peace each have names with meanings deliberately opposite to their real purpose, the Ministry of Love is perhaps the most straightforward as "rehabilitated thought criminals" leave the Ministry as loyal subjects who have been brainwashed into adoring (loving) Big Brother, hence its name.[8]

Film adaptations[edit]

The character, as represented solely by a single still photograph, was played in the 1954 BBC adaptation by production designer Roy Oxley. In the 1956 film adaptation, Big Brother was represented by an illustration of a stern-looking disembodied head.

In the film starring John Hurt released in 1984, the Big Brother photograph was of actor Bob Flag. Both Oxley and Flag sported small moustaches.

Use as metaphor[edit]

| Part of a series on |

| Global surveillance |

|---|

| Disclosures |

| Systems |

| Agencies |

| Places |

| Laws |

| Proposed changes |

| Concepts |

| Related topics |

Since the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, the phrase "Big Brother" has come into common use to describe any prying or overly-controlling authority figure and attempts by government to increase surveillance. Big Brother and other Orwellian imagery are often referenced in the joke known as the Russian reversal.[9][10]

Iain Moncreiffe and Don Pottinger jokingly mentioned in their 1956 book Blood Royal the sentence: "Without Little Father need for Big Brother", referring to the Russian Revolution and the Soviet Union.[11]

The worldwide reality television show Big Brother is based on the novel's concept of people being under constant surveillance. In 2000, after the United States version of the CBS program Big Brother premiered, the Estate of George Orwell sued CBS and its production company Orwell Productions, Inc. in federal court in Chicago for copyright and trademark infringement. The case was Estate of Orwell v. CBS, 00-c-5034 (ND Ill). On the eve of trial, the case settled worldwide to the parties' "mutual satisfaction", but the amount that CBS paid to the Orwell Estate was not disclosed. CBS had not asked the Estate for permission. Under current laws, the novel will remain under copyright protection until 2044 in the United States, it entered the public domain in 2020 within the European Union.[12]

The magazine Book ranked Big Brother no. 59 on its "100 best characters in fiction since 1900" list.[13] Wizard magazine rated him the 75th-greatest villain of all time.[14]

The iconic image of Big Brother (played by David Graham) played a key role in Apple's "1984" television commercial introducing the Macintosh.[15][16] The Orwell Estate viewed the Apple commercial as a copyright infringement and sent a cease-and-desist letter to Apple and its advertising agency. The commercial was never televised again,[17] though the date mentioned in the ad (24 January) was but two days later, making it unlikely that it would have been re-aired. Subsequent ads featuring Steve Jobs for a variety of products have mimicked the format and appearance of that original ad campaign, with the appearance of Jobs nearly identical to that of Big Brother.[18][19]

China's Social Credit System has been described as akin to "Big Brother" by detractors, where citizens and businesses are given or deducted good behavior points depending on their choices,[20] though new reports say the system doesn't work that way.[21]

See also[edit]

- Big Brother Awards

- Little Brother

- Memory hole

- National Security Agency

- New World Order (conspiracy theory)

- Totalitarianism

References[edit]

- ^ Strouf, Judie L. H. (2005). The literature teacher's book of lists. Jossey-Bass. p. 13. ISBN 0787975508.

- ^ Burgess, Anthony (1978). 1985.

- ^ "Douglas Kellner, George F. Kneller Philosophy of Education Chair, UCLA". ucla.edu. Archived from the original on 9 July 2011.

- ^ "From 1984 to One-Dimensional Man: Critical Reflections on Orwell and Marcuse" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2011.

- ^ Wells, H. G.; Star Begotten, Sphere Books, 1937, p. 101–102. "Most of us to the very end are obsessed by infantile cravings for protection and direction, and out of these cravings come all these impulses towards slavish subjugation towards gods, kings, leaders, heroes, mystical personifications like the People, My Country Right or Wrong, the Church, the Party, the Masses, the Proletariat. Our imaginations hang on to some such Big Brother idea almost to the end. We will accept almost any self-abasement rather than step out of the crowd and be full-grown individuals."

- ^ The sacred in twentieth-century politics : essays in honour of Professor Stanley G. Payne. Stanley G. Payne, Robert Mallett, Roger Griffin, John S. Tortorice. Basingstoke [England]: Palgrave Macmillan. 2008. ISBN 978-0-230-24163-3. OCLC 435833495.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Ulysses p. 478

- ^ a b Orwell, George (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- ^ Dix, Willard (27 December 2017). "Big Data's Influence On College Admission Is Growing". Forbes.

- ^ Lauchlan, Iain (2010). "Laughter in the dark: Humour under Stalin". Press Universitaires de Perpignan.

- ^ Iain Moncreiffe & Don Pottinger (1956). Blood Royal. Thomas Nelson and Sons. p. 18.

- ^ Drotner, Kirsten. "New Media, New Options, New Communities?" (PDF) (PDF). Nordicom. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ^ Christine Paik (19 March 2002). "100 Best Fictional Characters Since 1900". NPR.

- ^ Wizard #177

- ^ Remembering the '1984' Super Bowl Mac ad ZDNet, 23 January 2009

- ^ Apple's 'Big Brother' sequel BBC News, 30 September 2009

- ^ William R. Coulson ‘Big Brother’ is watching Apple: The truth about the Super Bowl's most famous ad The Dartmouth Law Journal, 25 June 2009 Archived 25 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Farrell, Nick (9 October 2009). "Steven Jobs is the new Big Brother". the Inquirer. Archived from the original on 10 October 2009.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Gianatasio, David (16 December 2010). "Steve Jobs (once again) cast as Big Brother". AdWeek.

- ^ "Big brother: China's data-driven Social Credit system sounds like a sci-fi dystopia". The National. 26 September 2018.

- ^ "China's social credit score – untangling myth from reality | Merics". merics.org. 11 February 2022. Retrieved 10 August 2022.