Prazosin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Minipress, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682245 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | α1 blocker |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~60% |

| Protein binding | 97%[4] |

| Onset of action | 30–90 minutes[5] |

| Elimination half-life | 2–3 hours[4] |

| Duration of action | 10–24 hours[4] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.038.971 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

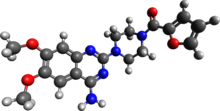

| Formula | C19H21N5O4 |

| Molar mass | 383.408 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Prazosin, sold under the brand name Minipress among others, is a medication used to treat high blood pressure, symptoms of an enlarged prostate, and nightmares related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[6] It is an α1 blocker.[6] It is a less preferred treatment of high blood pressure.[6] Other uses may include heart failure and Raynaud syndrome.[7] It is taken by mouth.[6]

Common side effects include dizziness, sleepiness, nausea, and heart palpitations.[6] Serious side effects may include low blood pressure with standing and depression.[6][7] Prazosin is a non-selective inverse agonist of the α1-adrenergic receptors.[6] It works to decrease blood pressure by dilating blood vessels and helps with an enlarged prostate by relaxing the outflow of the bladder.[6] How it works in PTSD is not entirely clear.[6]

Prazosin was patented in 1965 and came into medical use in 1974.[8] It is available as a generic medication.[6] In 2021, it was the 183rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 2 million prescriptions.[9][10]

Medical uses

[edit]Prazosin is active after taken by mouth and has a minimal effect on cardiac function due to its α1-adrenergic receptor selectivity. When prazosin is started, however, heart rate and contractility can increase in order to maintain the pre-treatment blood pressures because the body has reached homeostasis at its abnormally high blood pressure. The blood pressure lowering effect becomes apparent when prazosin is taken for longer periods of time. The heart rate and contractility go back down over time and blood pressure decreases.

The antihypertensive characteristics of prazosin make it a second-line choice for the treatment of high blood pressure.[11]

Prazosin is also useful in treating urinary hesitancy associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia, blocking α1-adrenergic receptors, which control constriction of both the prostate and urethra. Although not a first-line choice for either hypertension or benign prostatic hyperplasia, it is a choice for people who present with both problems concomitantly.[11]

During its use for urinary hesitancy in military veterans in the 1990s, Murray A. Raskind and colleagues discovered that prazosin appeared to be effective in reducing nightmares. Subsequent reviews indicate prazosin is effective in improving sleep quality and treating nightmares related to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[12][13]

Prazosin is used off-label in the treatment of insomnia for its sedative effects.[14][15] Prazosin is an inverse agonist at α1-adrenergic receptors;[15] these receptors are expressed on dendrites that noradrenergic neurons synapse onto in the brain. Some of the noradrenergic pathways in the central nervous system form part of the ascending reticular activating system, which promotes arousal when stimulated.[16][17] Prazosin inhibits the output neurons of the noradrenergic pathways in that system, in turn causing sedation.[15]

The drug is usually recommended for severe stings from the Indian red scorpion.[18][19][20]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common (4–10% frequency) side effects of prazosin include dizziness, headache, drowsiness, fatigue, weakness, palpitations, and nausea.[3] Less frequent (1–4%) side effects include vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, edema, orthostatic hypotension, dyspnea, syncope, vertigo, depression, anxiety, nasal congestion, and rash.[3] A very rare side effect of prazosin is priapism.[3][21] One phenomenon associated with prazosin is known as the "first-dose response", in which the side effects of the drug — specifically orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, and drowsiness — are especially pronounced in the first dose.[3]

Orthostatic hypotension and syncope are associated with the body's poor ability to control blood pressure without active α-adrenergic receptors. The nasal congestion is exacerbated by changing body positions, because α1-adrenergic receptors also control nasal vascular blood flow and alpha blockers inhibit this, in the same way that alpha-adrenergic agonists have the opposite effect of being a decongestant.[22][23]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Prazosin is an α1-blocker that acts as a non-selective inverse agonist at α1-adrenergic receptors, including of the α1A-, α1B-, and α1D-adrenergic receptor subtypes.[24] It binds to these receptors with affinity (Ki) values of 0.13 to 1.0 nM for the α1Α-adrenergic receptor, 0.06 to 0.62 nM for the α1B-adrenergic receptor, and 0.06 to 0.38 nM for the α1D-adrenergic receptor.[25][26] It has much lower affinity for the α2-adrenergic receptors (Ki = 210–5,012 nM for the α2A-adrenergic receptor, 13–398 nM for the α2B-adrenergic receptor, and 10–200 nM for the α2C-adrenergic receptor).[25][26] The α1-adrenergic receptors are found in vascular smooth muscle, where they are responsible for the vasoconstrictive action of norepinephrine.[27] They are also found throughout the central nervous system.[28] α1-Adrenergic receptors have additionally been found on immune cells, where catecholamine binding can stimulate and enhance cytokine production.[29][30]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Prazosin has an onset of action of 30 to 90 minutes,[5] the elimination half-life of prazosin is 2 to 3 hours,[4] and its duration of action is 10 to 24 hours.[4]

Research

[edit]Prazosin has been said to be the only selective α1-adrenergic receptor antagonist which has been used in the treatment of insomnia to any significant degree.[14] It is used at doses of 1 to 12 mg for this purpose.[14] The combination of prazosin and the beta blocker timolol may produce greater sedative effects than either of them alone.[15]

Prazosin has been shown to prevent death in animal models of cytokine storm.[31] As a repurposed drug, prazosin is being investigated for the prevention of cytokine storm syndrome and complications of COVID-19 where it is thought to decrease cytokine dysregulation.[32][30][33]

References

[edit]- ^ "Prazosin (Minipress) Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. 26 November 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- ^ "Hypovase Tablets 0.5mg - Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). 26 April 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Minipress- prazosin hydrochloride capsule". DailyMed. 19 July 2021. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "Prazosin". drugs.com. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ a b Packer M, Meller J, Gorlin R, Herman MV (March 1979). "Hemodynamic and clinical tachyphylaxis to prazosin-mediated afterload reduction in severe chronic congestive heart failure". Circulation. 59 (3): 531–539. doi:10.1161/01.cir.59.3.531. PMID 761333.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Prazosin Hydrochloride Monograph for Professionals". Drugs.com. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- ^ a b British national formulary : BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 766. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ Fischer J, Ganellin CR (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 455. ISBN 9783527607495.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2021". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 15 January 2024. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ "Prazosin - Drug Usage Statistics". ClinCalc. Retrieved 14 January 2024.

- ^ a b Shen H (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-59541-101-3.

- ^ Zhang Y, Ren R, Sanford LD, Yang L, Ni Y, Zhou J, et al. (March 2020). "The effects of prazosin on sleep disturbances in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Sleep Medicine. 67: 225–231. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2019.06.010. PMC 6986268. PMID 31972510.

- ^ Reist C, Streja E, Tang CC, Shapiro B, Mintz J, Hollifield M (August 2021). "Prazosin for treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis". CNS Spectrums. 26 (4): 338–344. doi:10.1017/S1092852920001121. PMID 32362287. S2CID 218492349.

- ^ a b c Krystal AD (December 2015). "New Developments in Insomnia Medications of Relevance to Mental Health Disorders". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 38 (4): 843–860. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2015.08.001. PMC 5972036. PMID 26600112.

- ^ a b c d Atkin T, Comai S, Gobbi G (April 2018). "Drugs for Insomnia beyond Benzodiazepines: Pharmacology, Clinical Applications, and Discovery". Pharmacological Reviews. 70 (2): 197–245. doi:10.1124/pr.117.014381. PMID 29487083. S2CID 3578916.

- ^ Iwańczuk W, Guźniczak P (2015). "Neurophysiological foundations of sleep, arousal, awareness and consciousness phenomena. Part 1". Anaesthesiol Intensive Ther. 47 (2): 162–167. doi:10.5603/AIT.2015.0015. PMID 25940332.

- ^ Malenka RC, Nestler EJ, Hyman SE, Holtzman DM (2015). "Chapter 13: Sleep and Arousal". Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill Medical. p. 521. ISBN 9780071827706.

- ^ Bawaskar HS, Bawaskar PH (2008). "Scorpion sting: A study of the clinical manifestations and treatment regimes". Current Science. 95 (9): 1337–1341. JSTOR 24103245.

- ^ Bawaskar HS, Bawaskar PH (January 2007). "Utility of scorpion antivenin vs prazosin in the management of severe Mesobuthus tamulus (Indian red scorpion) envenoming at rural setting". The Journal of the Association of Physicians of India. 55: 14–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1038.366. PMID 17444339.

- ^ Pandi K, Krishnamurthy S, Srinivasaraghavan R, Mahadevan S (June 2014). "Efficacy of scorpion antivenom plus prazosin versus prazosin alone for Mesobuthus tamulus scorpion sting envenomation in children: a randomised controlled trial". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 99 (6): 575–580. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2013-305483. PMID 24550184. S2CID 37215729.

- ^ Bhalla AK, Hoffbrand BI, Phatak PS, Reuben SR (October 1979). "Prazosin and priapism". British Medical Journal. 2 (6197): 1039. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.6197.1039. PMC 1596841. PMID 519276.

- ^ Riechelmann H, Krause W (1 January 1994). "Autonomic regulation of nasal vessels during changes in body position". European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 251 (4): 210–213. doi:10.1007/BF00628425. PMID 7917253. S2CID 24405406.

- ^ Johnson DA, Hricik JG (1993). "The pharmacology of alpha-adrenergic decongestants". Pharmacotherapy. 13 (6 Pt 2): 110S–115S, discussion 143S-146S. doi:10.1002/j.1875-9114.1993.tb02779.x. PMID 7507588. S2CID 70981730.

- ^ "Prazosin: Biological activity". IUPHAR. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ a b "Prazosin". DrugBank.

- ^ a b "Prazosin Ligand page". IUPHAR/BPS Guide to PHARMACOLOGY.

- ^ "Prazosin: Clinical data". IUPHAR. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ^ Day HE, Campeau S, Watson SJ, Akil H (July 1997). "Distribution of alpha 1a-, alpha 1b- and alpha 1d-adrenergic receptor mRNA in the rat brain and spinal cord". Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy. 13 (2): 115–139. doi:10.1016/S0891-0618(97)00042-2. PMID 9285356. S2CID 28007564.

- ^ Heijnen CJ, Rouppe van der Voort C, Wulffraat N, van der Net J, Kuis W, Kavelaars A (December 1996). "Functional alpha 1-adrenergic receptors on leukocytes of patients with polyarticular juvenile rheumatoid arthritis". Journal of Neuroimmunology. 71 (1–2): 223–226. doi:10.1016/s0165-5728(96)00125-7. PMID 8982123. S2CID 53151786.

- ^ a b Konig MF, Powell M, Staedtke V, Bai RY, Thomas DL, Fischer N, et al. (July 2020). "Preventing cytokine storm syndrome in COVID-19 using α-1 adrenergic receptor antagonists". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 130 (7): 3345–3347. doi:10.1172/JCI139642. PMC 7324164. PMID 32352407.

- ^ Staedtke V, Bai RY, Kim K, Darvas M, Davila ML, Riggins GJ, et al. (December 2018). "Disruption of a self-amplifying catecholamine loop reduces cytokine release syndrome". Nature. 564 (7735): 273–277. Bibcode:2018Natur.564..273S. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0774-y. PMC 6512810. PMID 30542164.

- ^ "Preventing 'Cytokine Storm' May Ease Severe COVID-19 Symptoms". HHMI.org. Retrieved 24 May 2020.

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT04365257 for "Prazosin to Prevent COVID-19 (PREVENT-COVID Trial) (PREVENT)" at ClinicalTrials.gov