Dan White

Dan White | |

|---|---|

White in January 1978 | |

| Born | Daniel James White September 2, 1946 Long Beach, California, U.S. |

| Died | October 21, 1985 (aged 39) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning |

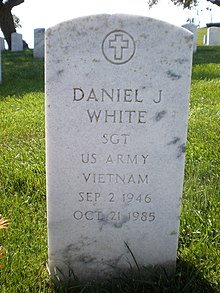

| Resting place | Golden Gate National Cemetery |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse |

Mary Burns (m. 1976) |

| Conviction(s) | Voluntary manslaughter (2 counts) |

| Criminal penalty | 7 years and 8 months imprisonment |

| Details | |

| Victims | George Moscone, 49 Harvey Milk, 48 |

| Country | United States |

| State(s) | California |

| Weapon | Smith & Wesson Model 36 |

| Member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from the 8th district | |

| In office January 8, 1978 – November 10, 1978 | |

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | Don Horanzy |

| Personal details | |

| Children | 3 |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Branch/service | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1965–1971 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Unit | 101st Airborne Division |

| Battles/wars | Vietnam War |

Daniel James White (September 2, 1946 – October 21, 1985) was an American politician who assassinated George Moscone, the mayor of San Francisco, and Harvey Milk, a member of the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, inside City Hall on November 27, 1978. White was convicted of manslaughter for the deaths of Milk and Moscone and served five years of a seven-year prison sentence. Less than two years after his release, he returned to San Francisco and later committed suicide.

Early life

[edit]Dan White was born in Long Beach, California, on September 2, 1946,[1] the second of nine children in a working-class Irish-American family. He grew up in the Visitacion Valley neighborhood of San Francisco and attended Archbishop Riordan High School, until he was expelled for violence in his junior year.[2] He went on to attend Woodrow Wilson High School[3] (later renamed Phillip and Sala Burton High School).

Career

[edit]White enlisted in the United States Army in June 1965. He served during the Vietnam War as a sergeant with the 101st Airborne Division between 1969 and 1970, and was honorably discharged in 1971.

Following a stint as a security guard at A. J. Dimond High School in Anchorage, Alaska, White returned to San Francisco and joined the San Francisco Police Department (SFPD). According to a SF Weekly newspaper account, he allegedly quit the force after reporting another officer for beating a handcuffed suspect.[2] White then joined the San Francisco Fire Department, in which he rescued a woman and her baby from a seventh-floor apartment.[2] The city's newspapers referred to him as "an all-American boy".[4]

Election as supervisor

[edit]In 1977, White was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors from District 8, which included several neighborhoods near the southeastern boundaries of San Francisco. At that time, supervisors were elected by district and not "at-large", as they had been before and then were again during the 1980s and 1990s.

White, a Democrat, had strong support from police and firefighter unions. His district was described by The New York Times as "a largely white, middle-class section that is hostile to the growing homosexual community of San Francisco." The Times stated that as a supervisor, White saw himself as the board's "defender of the home, the family and religious life against homosexuals, pot smokers and cynics".[5] White held a mixed record on gay rights, opposing the Briggs Initiative which sought to ban gays and lesbians from working in California's public schools, yet voting against an ordinance prohibiting discrimination against gays in housing and employment.[2]

Tenure as supervisor

[edit]Despite their personal differences, White and Harvey Milk, who was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors and was the first openly gay officeholder in California history, had several areas of political agreement and initially worked well together.[2] Milk was one of three people from City Hall invited to the baptism of White's newborn child shortly after the 1977 election.[2] White also persuaded Dianne Feinstein, then president of the Board of Supervisors, to appoint Milk chairman of the Streets and Transportation Committee.[2]

In April 1978, the Roman Catholic Church proposed a facility in White's district for juvenile offenders who had committed murder, arson, rape and other crimes, to be operated by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd. White strongly opposed the facility, while Milk supported it, and their difference of opinion led to a conflict between the two.[2]

Assassinations of George Moscone and Harvey Milk

[edit]Following a disagreement over a proposed drug rehabilitation center in the Mission District, White frequently clashed with Milk, as well as other members of the board.[6] On November 10, 1978, White resigned his seat as supervisor.[7][5] The reasons he cited were his dissatisfaction with what he saw as the corrupt practices of San Francisco politics, as well as the difficulty of earning a living without a police officer's or firefighter's salary, jobs he could not retain legally while serving as a supervisor. White had opened a baked potato stand at Pier 39, which failed to become profitable.[8] He reversed his resignation on November 14, after his supporters lobbied him to seek reappointment from Mayor George Moscone. Moscone initially agreed to White's request, but later refused the appointment at the urging of Milk and others.

On November 27, 1978, White visited City Hall with the later-declared intention of killing not only Moscone and Milk, but also two other San Francisco politicians, California Assembly Speaker Willie Brown (who himself would later serve as mayor) and Supervisor Carol Ruth Silver, whom he also blamed for lobbying Moscone not to reappoint him.[9] White climbed through a basement window carrying a Smith & Wesson Model 36 revolver and ten rounds of ammunition. By entering the building through the window, White managed to avoid the recently installed metal detectors. After entering Moscone's office, White pleaded to be reinstated as supervisor. When Moscone refused, White shot him in the shoulder, the chest, and twice in the head. He then walked to Milk's office, reloaded the gun and fatally shot Milk five times, firing the final two shots with the gun's barrel touching Milk's skull. White then fled City Hall, surrendering to the police at Northern Police Station, where he had formerly been a police officer. While being interviewed, White recorded a tearful confession, stating, "I just shot him."

Trial and "Twinkie defense"

[edit]At trial, White's defense team argued that his mental state at the time of the murders was one of diminished capacity due to depression. They argued that he was therefore not capable of premeditating the murders, and thus was not legally guilty of first-degree murder. Forensic psychiatrist Martin Blinder testified that White exhibited several behavioral symptoms of depression, including the fact that White had gone from being highly health-conscious to consuming sugary foods and drinks. Area newspapers quickly dubbed it the Twinkie defense. When the prosecution played a recording of White's confession, several jurors wept as they listened to what was described as "a man pushed beyond his endurance".[10] Many people familiar with City Hall claimed that it was common to enter through the window White had used to save time.[citation needed] An acquaintance of White's, who knew him from the SFPD, claimed that several officials carried weapons at this time and speculated that White carried the extra ammunition as a habit that police officers had.

White was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter and he was sentenced to seven years' imprisonment. Outrage within San Francisco's gay community over the sentence sparked the city's White Night riots. General disdain for the verdict led to the elimination of California's "diminished capacity" law.[11] In June 1979, psychiatrist Thomas Szasz, a critic of forensic psychiatry, gave a speech to a large audience in San Francisco calling the verdict a "travesty of justice" which he blamed on the diminished capacity defense.[12][13]

Alleged confession

[edit]In 1998, Frank Falzon, the SFPD homicide inspector to whom White had surrendered after the murders, said that he met with White in 1984, and that at this meeting White had confessed his intention to kill Brown and Silver along with Moscone and Milk. Falzon quoted White as having said, "I was on a mission. I wanted four of them. Carol Ruth Silver, she was the biggest snake ... and Willie Brown, he was masterminding the whole thing." Falzon indicated that he believed White, stating, "I felt like I had been hit by a sledge-hammer ... I found out it was a premeditated murder."[14]

Imprisonment and parole

[edit]White served five years of his seven-year sentence at Soledad State Prison and was paroled on January 7, 1984. Fearing he might be murdered in retaliation for his crimes, authorities secretly transported him to Los Angeles, where he served a year's parole.[15] At the completion of his parole, White sought to return to San Francisco; Feinstein, by now elected mayor, urged him not to return on the basis that doing so would jeopardize public safety.[16] Joel Wachs, a member of the Los Angeles City Council, also argued to keep White out of Los Angeles. White eventually did move back to San Francisco, where he lived with his wife and children.[17]

Suicide

[edit]

On October 21, 1985, less than two years after his release, White killed himself by carbon monoxide poisoning in his garage.[17] He was buried at Golden Gate National Cemetery in San Bruno, with a traditional government-furnished headstone issued for war veterans. He was survived by his two sons, his daughter and his widow.[17]

Media adaptations

[edit]The story of the assassinations is told in the Academy Award-winning documentary film The Times of Harvey Milk (1984), which was released a year before White committed suicide.

The American hardcore punk rock band Dead Kennedys altered the lyrics to the song "I Fought The Law" to tell the story of the assassinations from White's perspective, which was released on the 1987 compilation Give Me Convenience or Give Me Death.

The Law & Order episode "Pride" is heavily based on White's assassination of Harvey Milk. The killer in the episode is a former police officer and current politician who kills a victim known for his support for gay rights.

White was portrayed by Josh Brolin in the 2008 film Milk. The film depicted White from his first meeting with Milk up to and including Milk's death.[2][18] Brolin's nomination for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor was one of eight nominations the film received overall.

White's life, the assassinations, and his trial are covered in the 1984 book Double Play: The San Francisco City Hall Killings by Mike Weiss, which won the Edgar Award as Best True Crime Book of the Year. An expanded second edition, Double Play: The Hidden Passions Behind the Double Assassination of George Moscone and Harvey Milk, was issued in 2010 and updated White's story to include his life after prison and his suicide. The second edition also includes a DVD with a half-hour video interview of White.

Execution of Justice, a play by Emily Mann, chronicles the events leading to the assassinations. In 1999, the play was adapted to film for cable network Showtime, with Tim Daly portraying White.

Harvey Milk is an opera in three acts composed by Stewart Wallace to a libretto by Michael Korie. A joint commission by Houston Grand Opera, New York City Opera, and San Francisco Opera, it was premiered on January 21, 1995, by Houston Grand Opera.

Notes

[edit]- ^ "California Birth Index", hosted at ancestry. "Daniel James White, born September 2, 1946 Los Angeles County"

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Geluardi, John (January 29, 2008). "Dan White's Motive More About Betrayal Than Homophobia". SF Weekly. San Francisco, California: San Francisco Media Co. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- ^ Weiss, Mike (2010). Double Play: The Hidden Passions Behind the Double Assassination of George Moscone and Harvey Milk. San Francisco, California: Vince Emery Productions. pp. 213–216, 474.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (November 24, 2008). "Milk". Chicago Sun-Times. Chicago, Illinois: Sun-Times Media Group. Archived from the original on July 13, 2012. Retrieved March 27, 2009.

- ^ a b Turner, Wallace (November 28, 1978). "Suspect Sought Job". The New York Times. Retrieved May 31, 2017.

- ^ Lillian, Faderman (2018). Harvey Milk: His Lives and Death. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300222616. OCLC 1032649719.

- ^ "Mayor hunts a successor for White". San Francisco Examiner. November 11, 1978.

- ^ Sides, Josh. Erotic City: Sexual Revolutions and the Making of San Francisco. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2009. p. 164. Available at Internet Archive.

- ^ Weiss, Mike. (September 18, 1998). "Killer of Moscone, Milk had Willie Brown on List", San Jose Mercury News, Page A1

- ^ Knappman, Edward W. (1995). American Trials of the 20th Century. Detroit: Visible Ink Press. p. 464. Retrieved November 14, 2024.

- ^ Pogash, Carol (November 23, 2003). "Myth of the 'Twinkie defense'". San Francisco Chronicle. p. D-1. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ^ Winer, Paul (July 1979). "Was Psychiatry Dan White's Accomplice?". Noe Valley Voice. Retrieved March 18, 2017 – via archive.org.

- ^ Szasz, Thomas (August 6, 1979). "How Dan White Got Away With Murder". Inquiry. San Francisco, California: 17–21. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Weiss (1998).

- ^ Dolan, Maura (January 7, 1985). "Killed S.F. Mayor, Supervisor in '78 : Parole Ends; White Now Free to Leave L.A. County". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 26, 2023.

- ^ "Killed S.F. Mayor, Supervisor in '78 : Parole Ends; White Now Free to Leave L.A. County". Los Angeles Times. January 7, 1985. Retrieved September 16, 2023.

- ^ a b c Lindsey, Robert (October 22, 1985). "Dan White, Killer Of San Francisco Mayor, A Suicide". The New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2008.

- ^ "Edelstein D. 'Milk' Is Much More Than A Martyr Movie". NPR. November 26, 2008. Retrieved January 3, 2009.

References

[edit]- "Dan White: SFPD Interrogation Audio (November 27, 1978)". Bay Area Radio Museum, Gene D'Accardo/KNBR Collection. 1978. Archived from the original on February 16, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- Weiss, Mike (September 17, 1998). "Dan White wanted to kill Willie Brown on day he murdered San Francisco mayor, Harvey Milk". San Jose Mercury News.

- Weiss, Mike (2010). Double Play: The Hidden Passions Behind the Double Assassination of George Moscone and Harvey Milk, Vince Emery Productions. ISBN 9780982565056

External links

[edit]- 1946 births

- 1985 deaths

- 20th-century American criminals

- American assassins

- 20th-century American firefighters

- American male criminals

- United States Army personnel of the Vietnam War

- American people convicted of manslaughter

- American politicians who died by suicide

- American prisoners and detainees

- American people of Irish descent

- Burials at Golden Gate National Cemetery

- California Democrats

- Harvey Milk

- Military personnel from California

- People from Long Beach, California

- Prisoners and detainees of California

- San Francisco Board of Supervisors members

- San Francisco Police Department officers

- Suicides by carbon monoxide poisoning

- Suicides in California

- United States Army soldiers

- 1985 suicides