People's Liberation Army at the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre

This article has an unclear citation style. (June 2023) |

| People's Liberation Army at the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests | |||||||

Chinese tanks in Beijing, June 1989 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Demonstrators | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Student leaders: Workers: Intellectuals: | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 150,000–350,000 troops[1] | 50,000–100,000 demonstrators[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

15 verified killed including 7 KIA[a] 23 killed including 10 PLA and 13 PAP[b] ~5000 wounded[b] 60+ armored personnel carriers 30+ police cars 1,000+ military trucks 120+ other vehicles[6] |

218 killed[c] hundreds to ~2,600 killed[d] 7,000+ wounded | ||||||

During the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre in Beijing, the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA) played a decisive role in enforcing martial law, using force to suppress the demonstrations in the city.[13] The killings of protestors in Beijing continue to taint the legacies of the party elders, led by Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, and weigh on the generation of leaders whose careers advanced as their more moderate colleagues were purged or sidelined at the time.[13] Within China, the role of the military in 1989 remains a subject of private discussion within the ranks of the party leadership and PLA.[13]

Deployment during initial stages of protests

[edit]

The student movement in Beijing in the spring of 1989 was triggered by the death of former CCP General Secretary Hu Yaobang on April 15. Well before martial law was declared on May 19, the government called army troops into the city to help the police maintain order. On April 22, the Beijing Garrison's 13th Safeguard Regiment (3rd Guard Division) and nearly 9,000 soldiers from the 38th Army (112th Division, 6th Armored Division, engineer and communications regiments) were deployed around the Great Hall of the People during Hu's funeral.[14] Outside the Hall, in Tiananmen Square, nearly 100,000 students had gathered on the night of April 21 to mourn Hu.[15]

The 38th Army was called into Beijing a second time, after the publication of the April 26 Editorial, to join Beijing Garrison troops in guarding Tiananmen Square against protesting students.[14] Several hundred thousand students marched from campus through the city centre on April 27, but did not enter the square.[15] About 5,100 troops were involved in this second deployment.[15] There were no clashes with civilians and the troops pulled out on May 5.[15] The Beijing Garrison troops were called upon to guard the Great Hall on May 4, for the Asian Development Bank board meeting, and from May 13–17

Imposition of martial law

[edit]

On May 11, Chinese President Yang Shangkun met with Deng privately to discuss the causes of the student movement, the popular support it was receiving and why it was difficult to halt.[16] Deng explained that the demand of the people against official corruption was acceptable but the motive of some people using this demand as a pretext to overthrow the Communist Party was not.[16] He added that the party must use peaceful means to resolve the student movement but the Politburo must be prepared to act decisively.[16] On May 13, as the students embarked on a hunger strike in Tiananmen Square, Yang and the CCP General Secretary Zhao Ziyang gave Deng a private briefing.[17] Deng, who was the Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), expressed the impatience of party elders with the government's inability to end the student movement which had been active for nearly a month.[17] He reiterated the need to act decisively.[17]

Removal of Zhao Ziyang

[edit]

On the night of May 16, the five members of the CCP Politburo's Standing Committee, Zhao Ziyang, Li Peng, Qiao Shi, Hu Qili and Yao Yilin, along with President Yang Shangkun, Bo Yibo, the deputy director of the Central Advisory Commission, held an emergency meeting and agreed to (1) solicit the views of Deng Xiaoping and (2) have Zhao Ziyang negotiate with the hunger-striking students.[18] On May 17, the five Standing Committee members visited Deng's residence, where Deng made clear that no more concessions could be made to the students and that the time had come to call in the military to impose martial law.[19] The Standing Committee members agreed to convene in the evening to discuss how to implement martial law.[18] That night, the five Standing Committee members could not agree on whether to impose martial law, with Li Peng and Yao Yilin in support, Zhao Ziyang and Hu Qili in opposition and Qiao Shi abstaining.[20] Zhao offered to resign as Party General Secretary, but was dissuaded by Yang and asked for three days of sick leave.[20] Subsequently, Zhao Ziyang ceased to have political influence.[20]

On the morning of May 18, the Standing Committee, minus Zhao, along with party elders Chen Yun, Li Xiannian, Peng Zhen, Deng Yingchao, Bo Yibo, and Wang Zhen, along with Central Military Commission members Qin Jiwei, Hong Xuezhi and Liu Huaqing gathered at Deng's residence.[20] At this meeting, the leadership resolved: (1) to impose martial law on the morning of May 21, (2) hold an expanded meeting with military and Beijing government officials on May 19, (3) have Yang Shangkun make arrangements with the military to establish a martial law command, (4) explain the decision to the two remaining PLA Marshals, Nie Rongzhen and Xu Xiangqian, and (5) inform provincial-level party committees of the Party Center's decision.[20] On the afternoon of the May 18, the Central Military Commission appointed Liu Huaqing as the commander-in-chief of martial law operations with Chi Haotian, then PLA chief of staff, and Zhou Yibing, commander of the Beijing Military Region, as his deputies.[21] The military forces enforcing martial law would be drawn mainly from the Beijing, Jinan and Shenyang Military Regions.[21] Liu, Chi and Yang Shangkun then reported to Deng that the martial law force would mobilize 180,000 PLA and People's Armed Police personnel.[21]

By May 18, the protests in Tiananmen Square had reached one million supporters.[22] The protests caused deep divisions within the senior party leadership as well as the ranks of the PLA. On May 17, over 1,000 men from the People's Liberation Army's General Logistics Department showed their support for the movement by marching to Tiananmen Square, and they received enthusiastic applause from onlookers.[23]

The decision to impose martial law was initially resisted by Defense Minister Qin Jiwei.[13] After attending the meeting at Deng's home, Qin declined to send the martial law order to the military right away, citing the need to receive party approval. Zhao Ziyang, as General Secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, was nominally head of the party. Qin called Zhao's office, hoping that Zhao would call off the martial law order.[13] He waited four hours for Zhao's reply, which never came.[13] Unbeknownst to Qin, Zhao had lost the power struggle and was purged from the leadership. Qin later publicly supported the military crackdown but his authority diminished thereafter.[13]

Martial law declared – May 20

[edit]Though martial law was scheduled for May 21, news of the impending order was leaked to the public, so the timetable was moved up.[24] Premier Li Peng hastily announced martial law in the early morning hours of May 20.[24] The order, declared pursuant to Article 89, Section 16 of the PRC Constitution, was to come into effect at 10:00 am in eight urban districts of Beijing.[24]

On May 20, eight retired generals, including former defense minister Zhang Aiping, signed a one-sentence letter opposing the use of force:

We request that troops not enter the city and that martial law not be carried out in Beijing.

— Ye Fei, Zhang Aiping, Xiao Ke, Yang Dezhi, Chen Zaidao, Song Shilun, Wang Ping and Li Jukui, May 20, 1989 letter to the Central Military Commission[25]

Mobilization

[edit]On May 19, the Central Military Commission began mobilizing PLA units in anticipation of the announcement of martial law order. In addition to the Beijing and Tianjin Garrisons, at least 30 divisions were sent to Beijing from five of the country's seven military regions.[citation needed] At least 14 of PLA's 24 army corps sent troops. Reliable estimates place the number of troops mobilized in the range of 180,000 to 250,000.[26]

Xu Qinxian's defiance

[edit]The extraordinary scale of the mobilization may have been motivated by concerns of insubordination. Xu Qinxian, the commander of the 38th Army, the best-equipped army corps of the Beijing Military Region, refused to enforce the martial law order. Xu said he could not comply with a verbal order to mobilize and demanded to see a written order. When told by the Beijing Military Regional command that it "was wartime" and a written order would be provided later, Xu, who had spent time in Beijing earlier in the spring, said there was no war and reiterated his refusal to carry out the order.[27] President Yang Shangkun sent Zhou Yibing, the commander of the regional command to Baoding to persuade Xu.[25] Xu asked Zhou whether the three principals of the Central Military Commission had approved the martial law order. Zhou replied that while Deng Xiaoping, the chairman, and Yang Shangkun, the secretary-general, had approved, Zhao Ziyang, the first vice-chairman, had not. Without Zhao's approval, Xu refused to act on the order and asked for sick leave. He was court-martialled and the 38th Army under his replacement mobilized to enforce the martial law order.

After Xu's insubordination, the 12th Army, which Deng Xiaoping had personally led during the Chinese Civil War, was airlifted from Nanjing.[28] The 12th Army was the only unit mobilized from the Nanjing Military Region.

Units mobilized

[edit]

Wu Renhua's study has identified the involvement of the following units in martial law operations.[citation needed]

- Beijing Garrison: 1st and 3rd Guard Divisions.

- Tianjin Garrison (Headquartered in Ji County, Tianjin): 1st Tank Division. Motorized transport from Ji County.

- 14th Artillery Division (Headquartered in Huailai, Hebei): Five artillery battalions. Rail transport from Shacheng, Hebei.

- 24th Army (headquartered in Chengde, Hebei): 70th Infantry Division, 72nd Infantry Division, 7th Garrison Brigade. Motorized transport from Luanping and Luan County.

- 27th Army (headquartered in Shijiazhuang, Hebei): 79th and 80th Infantry Divisions, Artillery Brigade. Motorized transport from Xingtai, Huolu and Handan.

- 28th Army (headquartered in Datong, Shanxi): 82nd and 83rd Infantry Divisions. Motorized transport from Hongdong, and Jining, Inner Mongolia.

- 38th Army (headquartered in Baoding, Hebei): 112th and 113th Infantry Divisions, 6th Tank Division, Artillery Brigade, Engineering Battalion, Communications Battalion. Motorized transport from Baoding, Mancheng, and Xincheng County, Hebei.

- 63rd Army (headquartered in Taiyuan, Shanxi): 187th and 188th Infantry Divisions. Motorized transport from Yuci and Yizhou.

- 65th Army (headquartered in Zhangjiakou, Hebei): 193rd and 194th Infantry Divisions, 3rd Reserved Division. Motorized transport from Xuanhua.

- 20th Army (headquartered in Kaifeng, Henan): 58th and 128th Infantry Divisions. Motorized transport from Xuchang and Dengfeng.

- 26th Army (headquartered in Laiyang, Shandong): 138th Infantry Division. Airlifted from Jiao County

- 54th Army (headquartered in Xinxiang, Henan): 127th and 162nd Infantry Divisions. Motorized transport from Luoyang and Anyang.

- 67th Army (headquartered in Zibo, Shandong): 199th Infantry Division. Motorized transport from Zouping.

- 39th Army (headquartered in Yingkou, Liaoning): 115th and 116th Infantry Divisions, Communications Battalion. Rail and motorized transport from Gai County and Xincheng County.

- 40th Army (headquartered in Jinzhou, Liaoning): 118th Infantry Division, Artillery Brigade. Motorized transport from Yi County, Liaoning and Jinzhou.

- 64th Army (headquartered in Dalian, Liaoning): 190th Infantry Division. Motorized transport from Dalian.

- 12th Army (headquartered in Xuzhou, Jiangsu): 34th, 36th, and 110th Infantry Divisions, Artillery Brigade, Anti-Aircraft Battalion. Airlifted from Xuzhou and Nanjing.

- 15th Airborne Corps (headquartered in Xiaogan, Hubei): 43rd and 44th Airborne Brigades. Airlifted from Kaifeng and Guangshui, Hubei.

Most of the soldiers were from peasant families who had never been to Beijing and did not understand the situation they were about to confront. Many privately looked forward to their first trip to the capital and expected to be welcomed by residents. The military units from other regions spoke a different northern dialect than the Beijing citizens, adding to the confusion.[29] The soldiers were strictly prohibited from communicating with residents. This language barrier would limit curious soldiers in finding information on the student movement other than what they have been told by their chain of command.

Some mobilized units encountered civilian protesters before reaching Beijing. On the afternoon of May 19, residents in Baoding blocked four battalions of the 38th Army from leaving the city.[30] The 38th Army was forced to take different routes out of Baoding before reconvening on the highway to Beijing.[30] The 27th Army was also blocked on May 19 in Baoding by crowds who chanted anti-corruption slogans and spat on the soldiers, and was forced to re-route their approach on Beijing via Zhuozhou.[31] A detachment of the 64th Army traveling by train was blocked for two days by Tangshan students and residents who laid on the railway at Qian'an, Hebei from May 21–23.[32]

Attempt to enforce martial law on May 20–23

[edit]

On the night of May 19, advanced units from the 27th, 38th and 63rd Armies had already reached Beijing before martial law was publicly declared. But news of martial law having been leaked, students and city residents had also organized to block the troops in the outer suburbs.[37] On May 20, military units from the 24th, 27th, 28th, 38th, 63rd, 65th, Beijing Garrison Command, 39th, 40th, 54th and 67th Armies advanced on the city from all directions.[38] They were stopped and surrounded by tens of thousands of civilians who erected roadblocks and crowded around convoys at Fengtai, Liuliqiao, Shazikou, Hujialou, Gucheng, Qinghe, Wukesong, Fuxing Road and other points outside the Third Ring Road.[39] The 15th Airborne Corps landed at the Nanyuan Airport south of the city.[39] Airlifts continued into Nanyuan continued for the next three days. Five helicopters of the 38th Army appeared over Tiananmen Square and dropped leaflets calling on protesters to vacate the square.[33][40] The 65th Army made several efforts to advance on Tiananmen Square from the west but were forced to pull back into the Shijingshan and Haidian Districts.[39] The only unit that advanced into the city was the 14th Artillery Division which traveled by train from Shahe but this unit was surrounded by civilians once it reached the Beijing railway station.[39]

Many troops remained surrounded for several days. During this ordeal, encounters between troops and students were mostly peaceful. Some students had trained with the 38th in the summers as members of the army reserve.[41] In some places, troops and protesters sang traditional Maoist songs together, and residents brought the stranded soldiers food and water.[42]

Dajing Incident

[edit]At Dajing in Fengtai District, clashes broke out between demonstrators and troops.[43] On the night of May 19, as the 337th, 338th, artillery and armored regiments of the 38th Army's 113th Division advanced toward the Dajing Bridge, several students and residents blocking their advance were injured in clashes with riot police who were attempting to clear the way.[43] The crowd managed to pin the units on the bridge and nearby Shawo Village.[44] Though some units retreated to a nearby middle school, other units were stranded for three days and four nights.[45] On May 22, the regiment commissars negotiated with student leaders in Tiananmen Square to permit the units to retreat.[46] Talks broke down when the students insisted that the soldiers leave their vehicles and weapons.[46] At 8:00 p.m., the troops locked arms and pushed their way toward a Fengtai West Warehouse, and were attacked by the crowd, resulting in scores of injured soldiers.[43][47] Several students trying to protect the troops were also hit by rocks.[47][43] 10 suspects, none of whom were students, were later arrested.[43]

Pullback

[edit]On May 24, PLA troops withdrew from urban Beijing.[48] The failed attempt to control the growing protesters in Beijing forced the party leaders to call in additional PLA units. PLA soldiers were kept in isolation and underwent re-education to instill and reinforce the belief that a turmoil in the capital needed to be suppressed.[49]

Enforcement of martial law

[edit]On June 2, Deng Xiaoping and several party elders met with the three remaining Politburo Standing Committee members, Li Peng, Qiao Shi and Yao Yilin.[50] They agreed to clear the square so "the riot can be halted and order be restored to the Capital."[50] At 4:30pm on June 3, the three politburo members met with Central Military Commission members Qin Jiwei, Hong Xuezhi, Liu Huaqing, Chi Haotian and Yang Baibing, PLA General Logistics chief Zhao Nanqi, Beijing Party Secretary Li Ximing, mayor Chen Xitong, State Council secretariat Luo Gan, Beijing Military Region commander Zhou Yibing and political commissar Liu Zhenhua to discuss the final steps for enforcing martial law:[50]

- The operation to quell the counterrevolutionary riot would begin at 9:00 p.m.

- Military units should converge on the square by 1:00 a.m. on June 4 and the square must be cleared by 6:00 a.m.

- No delays will be tolerated.

- No person may impede the advance of the troops enforcing martial law. The troops may act in self-defense and use any manner to clear impediments.

- State media will broadcast warnings to citizens.

That evening, the leaders monitored the progress of the troops from headquarters in the Great Hall of the People and Zhongnanhai.[50] Security at Zhongnanhai compound was reinforced by troops from the 1st and 3rd Safeguard Divisions of the Beijing Garrison, units of the 65th Army.[50] Later, the 27th Army also sent units.[50]

Covert infiltration June 2–3

[edit]On June 2, several army units were moved covertly into Great Hall of the People on the west side of the square and the Ministry of Public Security compound east of the square.[51]

- The 27th Army sent most of its troops, dressed in plain clothes, in unmarked buses that moved from Fengtai District toward the Great Hall on the night of June 2.[52] The movements were detected by residents, who pinned down the convoy at various points in southern Beijing, including about 2,000 near Taoranting Park.[52] Many troops disembarked from their vehicles and either proceeded on foot or took refuge in government buildings along route.[52] By the early morning hours of June 4, about 7,000 troops of the 27th Army had assembled at the Great Hall of the People.[53] Another 800 took temporary refuge at a sports school in Dongdan.[53]

- The 65th Army divided its soldiers into small groups of three to five, each with one who was familiar with the city and could speak Beijing-accented Mandarin. They were dressed in plain clothes and dispatched by a variety of means from Shijingshan on June 2 — on bus, train, subway or on foot — to the Zhongnanhai Compound.[54] From there, the troops then moved into the Great Hall of the People via tunnel.[54] By the night of June 2, over 10,000 troops of the 65th had assembled in the Great Hall.[54]

- The 24th Army left its rendezvous point in Tongzhou on the night of June 2 and entered the city under cover of darkness with most troops leaving vehicles and marching on foot.[55] They were discovered by the city merchants' motorcycle patrols, which called out to sleeping residents to form blockades.[55] The 24th Army did not head to toward to the square as residents had suspected, but settled into the Ministry of Public Security Complex behind the History Museum.[55]

- The 63rd Army's 187th Division, dressed in plain clothing, traveled by subway from Shijingshan into the city.[56] At the time, the Beijing Subway did not reach Tiananmen Square, so the troops emerged from stations at Qianmen, Chongwenmen and the Beijing railway station and walked to the Great Hall of the People.[56] On the afternoon of June 2, city residents noticed groups of young people streaming out of the subway, which had previously been shut down, and rushed to block the subway exits.[56] Student patrols demanded groups of suspicious-looking men to produce identification, forcing soldiers in disguise to scatter. Only two-thirds of the 187th Division managed to reach the Great Hall by 3:00 am on June 3, though the remainder eventually rejoined the unit.[57] The 187th spent most of June 3 guarding the perimeter of the Great Hall, sometimes in tense standoff, with student demonstrators.[58]

Many of the troops that infiltrated the city center in disguise did not carry weapons, which had to be delivered to them in unmarked vehicles. On the morning of June 3, a bus carrying a company of soldiers in the 27th Army, dressed in plain clothes, and hidden cargo of over 100 assault rifles, five light machine guns, two radios and over 10,000 rounds of ammunition was intercepted by students at Liubukou, just west of Tiananmen Square.[59] The students surrounded the bus and seized some of the weapons as evidence of the government's ill-intent.[59] At 2:05 pm, over 800 soldiers and People's Armed Police in riot gear from the Beijing Garrison rushed out of Zhongnanhai to retake the weapons cache.[60] Simultaneously, thousands of unarmed troops from the 27th and 63rd Armies emerged from the Great Hall to divert the crowds' attention.[61] The PAP units with clubs and riot gear fought through walls of protesters to seize control of the weapons.[62] For the first time during the 1989 Tiananmen Protests, the police fired tear gas to repel protesters.[63]

Troop movements – June 3–4

[edit]At 6:30 pm on 3 June, the Beijing Municipal Government and Martial Law Command issued an emergency announcement advising citizens to "stay off the streets and away from Tiananmen Square". [64] This announcement was broadcast for several hours across radio and television. [64] Meanwhile, protesters used student loudspeakers in various university campuses in Beijing to call for students and citizens to arm themselves and assemble at intersections and the Square.[64]

From the west

[edit]

On June 3, at 8:00 p.m., the 38th Army, led by interim commander Zhang Meiyuan, began to advance from military office compounds in Shijingshan and Fentai District in western Beijing along the western extension of Chang'an Avenue toward the square to the east.[51] At 9:30 p.m, this army encountered a blockade set up by protesters at Gongzhufen in Haidian District.[65] Troops armed with anti-riot gear clashed with the protesters, firing rubber bullets and tear gas, while the protesters threw rocks, bricks, and bottles at them.[65] Other troops fired warning shots into the air, which was ineffective.[65] At 10:10 pm, an army officer picked up a megaphone and urged the protesters to disperse. [65]

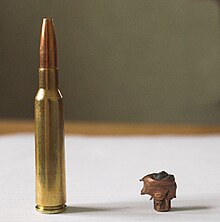

At about 10:30 p.m., the 38th Army opened fire on protesters at the Wukesong intersection on Chang'an Avenue, about 10 km west of the square.[65] [66] The crowds were stunned that the army was using live ammunition, and fell back towards the Muxidi Bridge.[65] Song Xiaoming, a 32-year-old aerospace technician, killed at Wukesong, was the first confirmed fatality of the night.[citation needed] The troops allegedly used expanding bullets, which expand and fragment upon entering the body and create larger wounds.[67] According to Wu Renhua's study, the 38th Army killed more civilian demonstrators than any other unit, despite its reputation at the time of being friendly to city residents.[citation needed] Fatalities were recorded all along Chang'an Avenue, at Nanlishilu, Fuxingmen, Xidan, Liubukou and Tiananmen. Among those killed was Duan Changlong, a Tsinghua University graduate student, who was allegedly shot in the chest as he tried to negotiate with soldiers at Xidan.[citation needed]

At 10:30 p.m., the 63rd Army's 188th Division advanced from the western suburbs, following the path cleared by the 38th Army, and reached the Great Hall of the People on the east side of the square.[51][unreliable source?] The 28th Army, which left Yanqing County in the far northwest on June 3, tried to follow this path along western Chang'an Avenue but its progress stalled at Muxidi early on the morning of June 4.[51]

The advance of the army was again halted at Muxidi, about 5 km west of the square, where they encountered another blockade made up of articulated trolleybuses that were placed across a bridge and set on fire.[68] An anti-riot brigade attempted to storm the bridge, but were driven back by a barrage of broken bricks the protesters had prepared beforehand. [69] Regular troops then rushed onto the bridge, chanting, "If no one attacks me, I attack no one; but if people attack me, I must attack them", and turning their weapons on the crowd. Soldiers alternated between shooting into the air and firing directly at protesters.[70][71][68] According to the tabulation of victims by Tiananmen Mothers, 36 people died at Muxidi, including Wang Weiping, a doctor tending to the wounded. As the battle continued eastward, the firing became indiscriminate, with "random, stray patterns" killing both protesters and uninvolved bystanders.[72][73] [70] Several were killed in the apartments of high-ranking party officials overlooking the boulevard.[71][73] Soldiers raked the apartment buildings with gunfire, and some people inside or on their balconies were shot.[74][71][75][73] The 38th Army also used armored personnel carriers to ram through blockades. [71] As the army advanced, fatalities were recorded along Chang'an Avenue. By far, the largest number occurred in the two-mile stretch of road running from Muxidi to Xidan, where "65 PLA trucks and 47 APCs ... were totally destroyed, and 485 other military vehicles were damaged."[72]

A noteworthy death near Xidan – that of 25-year-old 2nd Lieutenant Liu Guogeng, a PLA company commander – reveals stark differences between the narrative accounts that parties glorifying or vilifying the PLA offer regarding the battle.[76] Both sides recount that Liu's charred, disemboweled body was found hanging from a bus near Xidan, wearing only socks and a hat.[77] Graphic images of his corpse were published by both pro- and anti-PLA media.[76] According to the official account, Liu's unit was surrounded, and a few disabled vehicles fell behind the rest of the convoy. Liu then went on foot to retrieve his comrades, but was captured at Liubukou and beaten for an hour. He escaped, but was recaptured some distance west, killed and mutilated.[78] He was later declared a "national martyr" and "people's hero".[79] According to the alternative, anti-PLA account, Liu was captured and lynched after killing four people (including one child)[78] at close range with his assault rifle. Slogans describing his alleged deeds were scrawled on the side of the bus where his body had been hung.[80]

From the south

[edit]The 15th Airborne Corps and 54th Group Army left the Beijing Nanyuan Airport at 2:00 AM, advancing Tiananmen Square from the south, with PAP units serving as the lead elements.[38][81] They met resistance from demonstrators, who had set up roadblocks made up of buses and trucks.[38] Initial attempts by PAP troops to disperse the defenders with nightsticks were ineffective.[38] Tanks and armored personnel carriers were able to easily cut through the roadblocks, but resistance became stiffer as the PLA advanced further into the city. Urban fighters disabled armored vehicles using steel bars from road dividers to break their tracks and wheels, before covering them with blankets doused in gasoline and set on fire. PLA crews who exited the vehicles were attacked with rocks and molotov cocktails.[38] Larry Wortzel noted that this swarming tactic was clearly rehearsed and practiced, having been used by demonstrators in the same way in street fighting in other places around the city, especially during the battle at Muxidi, noting, "By this time, having seen their fellow soldiers killed, the troops were scared. Political commissars had told them for 2 weeks that there were “counter-revolutionary criminals” in the city. Predictably, the troops reacted by opening fire." [38] Throughout the fighting, disabled armored vehicles slowed the progress of the army's trucks and troops.[38]

The 20th Army under future defense minister Liang Guanglie, advanced north from Daxing County, and proceeded to the south of Tiananmen Square through Dahongmen, Yongdingmen and Zhengyangmen.[51] At 2:00 a.m., about 880 soldiers from the 173rd Regiment, 58th Division of the 20th Army, were surrounded by tens of thousands of city residents outside the east gate of the Temple of Heaven in Chongwen District. About 300 were pinned against the outside wall of the Temple complex. When the regiment commander told the crowd that his troops were hungry, thirsty and tired, residents brought soda, snacks and fruit and escorted injured soldiers to the hospital.[citation needed]

The 12th Army was airlifted to the Nanyuan Airport on June 4 and was not deployed on the city.[51]

From the east

[edit]

At 8:00 p.m., the 39th Army left the Sanjianfang Military Airport in Tong County and advanced eastward toward the square through Chaoyang and Dongcheng Districts.[51] The 67th Army also left Tong County and moved from Dingfuzhuang, Dabeiyao, Hujialou, Jianguomen, East Chang'an Avenue to Tiananmen Square.[51] The 14th Artillery Division departed from the Beijing railway station and moved toward the east side of the square.[82]

At 10:00 p.m., the first squad of the 1st Armored Division left Yangzha in Tong County and moved west along the Beijing-Tangshan Highway.[83] Earlier, at 4:00 pm, this unit had been ordered to move from Sanhe in Hebei to the Beijing Garrison Command barracks at Yangzha.[83] At Baliqiao, the first squad's advance was halted by a human chain of demonstrators and jack-knifed buses. At midnight, a vanguard unit of three APCs split from the main squad in search of a new route and moved over to the Beijing-Tianjin Highway.[83] The main squad followed. Over the next four hours, the armored units smashed through barricaded intersections at Shilipu, Balizhuang, Hujialou, Dabeiyao, and Jianguomen, and reached the square at about 5:00 am.[83] The rest of the first squad followed at 5:40 am.[83]

The second squad of the 1st Armored Division left Sanhe the night of June 3 and encountered numerous roadblocks before its advance was completely halted at Shuangjing, where residents barricaded the road with dozens of trucks and surrounded the convoy. Angry residents told the troops of bloodshed in the city and smashed the lights and machine gun mounts on some of vehicles.[83] Scores of soldiers were injured.[83] Division commander Xu Qingren and commissar Wu Zhongming chose not to harm civilians and stayed at Shuangjing for 13 hours from about 6:40 am to 7:40 pm, during which time residents brought food and water to the soldiers.[83] The tank units of the second squad did not reach the square until 1:40 am on June 5 and some of the troops arrived on June 7.[83]

Insubordination of 116th Division, 39th Army

[edit]On the evening of June 3, Xu Feng, the division commander, switched to plain clothes and carried out his own reconnaissance of the city.[84] When he returned, he told subordinates "not to look for him" and went into the division's communications vehicle.[84] Thereafter, the division maintained radio silence and did not advance on Beijing, except for the 347th Regiment under Ai Husheng, which complied with orders and went to Tiananmen Square on June 4.[84] On June 5, the rest of the division was escorted by other units to the square.[84] Xu Feng was later disciplined for passive resistance.[84]

From the north

[edit]The 40th Army departed the Beijing Capital Airport at 3:35 pm and advanced on the city from the northeast via the Airport Highway, Taiyanggong, Sanyuanqiao and Dongzhimen.[51]

The 64th Army left its assembly point at the Shahe Military Airport in Changping County north of the city and moved south along Madian, Qinghe, Xueyuan Road, Hepingli, to Deshengmen.[51]

Converging on the square – June 4

[edit]At about 1:30 a.m., the 38th Army and the 15th Airborne Corps arrived at the north and south ends of the square respectively.[citation needed] The 14th Artillery Division had reached the Museum of Chinese History, on the east side of the square, at 12:15 a.m.[82] The 27th and 65th Armies spilled out of the Great Hall of the People on the west side of the square. The 63rd Army held the east side of the square.[citation needed] The 24th, 39th, 54th Armies and the 14th Artillery Division controlled the perimeter of the square, and by 2:00 a.m., the encirclement was complete.[citation needed] Crowds trying to re-enter the square from East Chang'an Avenue were driven off by gunfire. At the time, several thousand students remained huddled around the Monument to the People's Heroes inside the square.[citation needed]

As the students debated what to do, Hou Dejian negotiated for safe passage out of the square with the army. At 3:30 a.m., at the suggestion of two doctors in the Red Cross camp, Hou Dejian and Zhuo rode in an ambulance to the northeast corner of the square and spoke with Ji Xinguo, the political commissar of the 336th Regiment, who relayed the request to command headquarters, which agreed to grant safe passage for the students to the southeast.[85] At 4:00 a.m., the lights on the square abruptly shut, signalling the end of the army's patience. To break the students' spirits, Company No. 5 of the 2nd Bridgade, 334th Regiment knocked down the Goddess of Democracy statue at the north end of the square.[86] At 4:30 a.m., the lights relit as the soldiers moved into action.

Under the leadership of brigadier commander Wu Yunping of the 44th Airborne Brigade, troops advanced on the Monument and at about 4:40 a.m., shot out the students' loudspeakers.[50] By then, the majority of the students had been persuaded by Liu Xiaobo and Hou Dejian to leave the square. The students left the square to the southeast. Some were beaten by soldiers along the way. Army vehicles then ran over the tent city, leading to conflicting accounts as to whether there were casualties inflicted as a result. By 5:30 a.m. the square was cleared.[citation needed] Debris was lifted out by helicopter.

At least three students were killed by lethal gunfire in and around the square. After the square was cleared, clashes between residents and soldiers continued for several more days. The military, especially the intelligence units, undertook to make massive arrests of "violent thugs." Some units engaged in torture.[citation needed]

Actions following clearance of the square

[edit]Tank encounters students at Liubukou

[edit]This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (May 2023) |

At about 5:20 a.m., the 1st Armored Division's first squad was ordered to disperse demonstrators around Zhongnanhai.[83] Under regiment commander Luo Gang and commissar Jia Zhenlu, eight tanks left the square and moved west along Chang'an Avenue.[83] Their advance was halted by several hundred students lying in the street, who refused to move despite verbal warnings and shots fired into the air.[83] The tanks then fired military-grade tear gas, which proved unbearable to the students, who scattered.[83] The tanks reached Xinhua Gate of Zhongnanhai at 7:25 a.m., where several stayed to guard the gate and others proceeded westward.[83] At the Liubukou intersection, the tanks came upon thousands of students, who had just vacated Tiananmen Square, and were walking in the bicycle lane on the side of the avenue back toward campus.[83] Three tanks fired tear gas at the students and one, No. 106, drove into the crowd, killing 11 and injuring at least nine, including Fang Zheng.[83] Luo Gang, who was promoted to the deputy division commander, claims in his memoirs that tanks under his command did not run over anyone.[83]

Insubordination of 28th Army at Muxidi

[edit]The 28th Army was notable for its passive enforcement of the martial law order. The unit, led by commander He Yanran and political commissar Zhang Mingchun and based in Datong, Shanxi Province, received the mobilization order on May 19.[87] They proceeded to lead the mechanized units to Yanqing County northwest of Beijing's city centre. When ordered to enter the city on June 3, the 28th encountered protesting residents along route but did not open fire and missed the deadline to reach Tiananmen Square by 5:30 a.m. on June 4.[87] At 7:00am, the 28th Army ran into a throng of angry residents at Muxidi on West Chang'an Avenue west of the square.[87] The residents told the soldiers of the killings from earlier in the morning and showed blood stained shirts of victims. At noon, Liu Huaqing, the commander of the martial law enforcement action, ordered Wang Hai, head of the PLA Air Force, to fly over Muxidi by helicopter and order by loudspeaker the 28th Army to counterattack.[87] But on the ground, the commanders of the 28th refused to comply.[87] Instead the troops abandoned their positions en masse. By 5:00 pm, many had retreated into the Military Museum of the Chinese People's Revolution nearby. Of all units involved in the crackdown, the 28th Army lost by far the most equipment, as 74 vehicles including 31 armored personnel carriers and two communications vehicles were burned.[87] The unit was later removed and ordered to undergo six months of reorganization.[87] Afterwards, all commanding officers were demoted and reassigned to other units.[87]

Demonstrations on East Chang'an Avenue

[edit]Later in the morning, thousands of demonstrators tried to enter the square from the northeast on East Chang'an Avenue, which was blocked by rows of infantry.[88] Many in the crowd were parents of the demonstrators who had been in the square.[88] As the crowd approached the troops, an officer sounded a warning, and the troops opened fire.[88] The crowd scurried back down the avenue in view of journalists in the Beijing Hotel.[88] Dozens of protesters were shot in the back as they fled.[88] Later, the crowds surged back toward the troops, who opened fire again, forcing them to retreat.[88][89] The crowd attempted several more times but could not enter the square, which remained closed to the public for two weeks.[90]

Students return to campus

[edit]Later in the morning, several thousand students walking back to campus encountered a convoy of the 64th Army's 190th Division near Xueyuan Street.[91] The students blocked the convoy and showed their commander the body of nine-year-old Lü Peng, who was killed by gunfire the night before at Fuxingmen.[91] The sight of the child enraged the crowds.[92] The commander ordered his men not to fire and pulled back. Later that afternoon, 27 vehicles of the 64th Army were burned near the Madian Bridge.[91]

June 5–7

[edit]On June 5, having secured the square, the military began to reassert control over thoroughfares through the city, especially Chang'an Avenue. A column of tanks of the 1st Armored Division left the square and heading east on Chang'an Avenue and came upon a lone protester standing in the middle of the avenue. The brief standoff between the man and the tanks was captured by Western media atop the Beijing Hotel. As the tank driver attempted to go around him, the man moved into the tank's path. He stood defiantly in front of the tanks for some time, then climbed up onto the turret of the lead tank to speak to the soldiers inside. After returning to his position in front of the tanks, the man was pulled aside by a group of people.[67] Charlie Cole, who was there for Newsweek, claimed that the men were Chinese government agents,[93] while Jan Wong, who was there for The Globe and Mail, thought that they were concerned bystanders.[94]

According to Li Xiaoming, an officer in the 116th Division, a soldier in his unit fired at a crowd that had surrounded other troops outside the Xinhua News Agency, defying orders to fire into the air or the ground to intimidate the crowd.[84] Li estimates that fewer than one out of 1,000 soldiers actually fired on crowds, for otherwise, "blood would have flowed like river through the streets" as it would take "only ten soldiers each emptying their magazine, to kill 300–400 people."[84]

On June 7, troops from the 39th Army fired on the diplomatic apartments along Jianguomen Outer Street after sniper fire from that direction reportedly shot and killed one soldier, Zang Lijie, and wounded three others.[84][95] Larry Wortzel, a military intelligence officer at the U.S. Embassy, stated that he received advance warning of the shooting with exact hours along with buildings and floors to avoid.[38]

Military resistance to martial law orders

[edit]Prior to June 3–4

[edit]PLA soldiers joined in on the demonstrations of the student movement in Tiananmen Square before and after the declaration of martial law on May 20, 1989.[96] On May 16, 1989; the same day that Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev met with Deng Xiaoping, 1,000 soldiers paraded with the students down Chang'an Boulevard.[97][98] On May 23, 1989, 100 naval cadets walked through Tiananmen Square chanting, "Down with Li Peng."[99] Soldiers were deployed to Beijing the night before and after martial law was declared. During their training they were taught to obey orders and not to question the demands of the party.[100] They were also instructed not to accept food from the students or participate in conversations with them.[101] However, not all PLA soldiers followed these orders. The people of Beijing offered food and drinks that were accepted by the troops which disobeyed the Chinese Communist Party's orders.[102] Chen Guang, who was deployed to suppress the movement on May 19, 1989, described the students as, "Very friendly, with bright smiles. Their spirit was welcoming."[103] When the army retreated the students held banners stating, "The PLA came on orders. We support you. There is no disorder in Beijing. You guys go on home."[104] Chen suggested that this treatment made him question his purpose in suppressing the movement. He stated, "All at once you felt like you hadn't understood this society... You start to think about these problems. Before that, you didn't have that kind of conscious."[105]

Then, on May 29, 1989, the high command of the Navy sent a report to the Party centre supporting its decision in introducing martial law.[106] However, naval officers also included concerns that were outlined in their report. They did not support the denunciation of Zhao Ziyang and worried about whether the Chinese Communist Party leadership was stable.[107] They also suggested that the CCP listen to the demands of the students especially in terms of public security, corruption, and the imbalance between wages.[107] Chairman of the Central Military Commission, Deng Xiaoping and his orders were met with resistance from both higher and medium ranking PLA officials after the declaration of martial law.[108] Many veterans and top military leaders also signed petitions against soldiers using force against the protesters such as: Nie Rongzhen, Xu Xiangqian, Zhang Aiping, and Ye Fei.[99]

On June 3–4

[edit]Scholars estimate that on the evening of June 3, 1989, Deng deployed 150,000 to 350,000 troops with heavy artillery to enter and surround Beijing.[1] However, many of the soldiers in the People's Liberation Army did not follow the orders to enforce martial law that night.[109] Some soldiers were emotionally conflicted and were hesitant to turn their weapons on the students. They believed that the PLA belonged to the people and that they were supposed to fight for them and not against them.[1] They were reminded of this sentiment by bystanders and protesters during their multiple attempts in clearing the square prior to and on the night of the massacre.[110]

Therefore, some PLA units did not have ammunition with them when they entered Beijing, including the 40th army unit.[111][112] Party officials reportedly suspected this unit of not following the martial law orders that were declared by Li Peng.[113] American journalists claimed that on the night of the massacre the 38th unit soldiers told civilians and bystanders that if they had weapons they would have used them against the soldiers firing on civilians.[112] In addition, some soldiers of the PLA willingly dismounted from tanks and other army vehicles and did not stop civilians from burning them down.[112] PLA soldier Chen Guang stated that desertion never crossed his mind, however, it did occur on the night of the massacre as approximately 400 soldiers deserted during the night of June 3. [114] [115] Chinese reports state that these soldiers were missing in action.[112]

Popular accounts state that Beijing police officers defended citizens and used their weapons against the incoming soldiers.[116]

Finally, Li Xiaoming was an officer in the 116th army division in the 39th group army and was one of the first soldiers to talk about the events of Tiananmen publicly. Some soldiers in the 116th army division did not support the violence against the students and felt empathy towards the victims of the massacre.[117] The division's commander Xu Feng refused to obey orders and pretended not to receive any messages from higher officials.[117] Therefore, on June 4, instead of entering the city, the unit continuously circled Beijing.[117] By June 5 the division was escorted into the city to help with the clean-up process. They were exposed to damaged infrastructure due to tanks and bullets, as well as blood stained clothes scattered around the square.[117]

After the Night of June 4

[edit]After the events of the massacre, thousands of PLA soldiers congregated in Beijing where infighting between the various units reportedly occurred.[113] Popular opinion of the massacre suggests that the 27th field army was to blame for the worst crimes against the civilians and students of Beijing during the night of the massacre, and was deemed the most loyal to Deng Xiaoping.[118] Therefore, rumours existed stating that this unit clashed with soldiers from the 16th army because, as some would suggest, it openly opposed the treatment of the students.[113] On June 6, 1989, two days after the square was cleared, the 27th field army kept their tanks and weapons pointed at the borders of Beijing against potential threats to the CCP, as well as on the suspected disloyal troops.[113] A unit of 400 men was kept under constant watch and had guns pointed towards them from the 27th field army to avoid any disloyal action.[113]

On the campus of Beijing's National Defence University, a poster was put up condemning the CCP's role in the suppression of the students on June 4.[99] It is suspected that it was put up by soldiers.[99]

Casualties

[edit]According to government sources, 10 PLA soldiers and 13 PAP soldiers were killed.[4][5] State-run media at the time reported that "tens" of soldiers, armed police and Beijing municipal police were killed and over 6,000 injured.[6] According to a later study by Wu Renhua, who participated in the protests, only 15 fatalities among soldiers and armed police could be verified.[3] Over half of these deaths were not directly caused by demonstrators:

- 6 soldiers from the 38th Army, Wang Qifu, Li Qiang, Du Huaiqing, Li Dongguo, Wang Xiaobing, and Xu Rujun were killed when the truck they were riding in flipped over and caught fire at Cuiwei Road at about 1:10 a.m. on June 4;[119]

- Yu Ronglu, a photographer in the propaganda unit of the 39th Army who was not in uniform while taking pictures and hit by gunfire (and counted as a "friendly fire" casualty) at about 2:00 a.m. on June 4;[119]

- Wang Jingsheng, a platoon commander from the 24th Army, died of a heart attack on July 4.[3]

The remaining seven deaths that may be counted as actual killed in action all occurred after the troops first opened fire on the crowds at 10:00 p.m. on June 3.[3]

- Liu Guogeng, a platoon commander in the 63rd Army, was killed at about 4:00 a.m. on June 4, just west of Xidan;[3]

- Cui Guozheng, a private in the 39th Army, was stabbed to death on a pedestrian bridge at Chongwenmen at about 4:40 am;[3]

- Ma Guoxuan, a platoon commander in the 54th Army, was attacked at 1:00 a.m. at Caishikou and died of his wounds at the Hospital of the People's Armed Police;[3]

- Wang Jinwei, a lieutenant in the 54th Army, died on South Xinhua Street at about 4:30 a.m. on June 4;[3]

- Li Guorui of the People's Armed Police, was wounded at the Fuchengmen Bridge at about 5:00 a.m. and later died at Renmin Hospital;[3]

- Liu Yanpo of the People's Armed Police, was wounded at Xidan at about 1:00 a.m. on June 4 and later died at Renmin Hospital;[3] and

- Zang Lijie, a private in the 39th Army, was hit by gunfire from the diplomatic apartments on Jianguomen Outer Street on June 7.[3]

Aftermath

[edit]

Rumors

[edit]In the days after June 4, rumors spread among Beijing residents that the 27th Army committed the most brutal atrocities while the 38th Army was friendly to the people.[120] The 27th Army was believed to be led by President Yang Shangkun's nephew and believed to be fanatically loyal to Yang.[121] Its soldiers were described by residents as "illiterate 'primitives' who know only how to kill."[122] Some soldiers were believed to have been drugged and been issued altered ammunition to increase injuries.[22] There were reports of unprovoked shootings of unarmed civilians in the back without warning.[123] and even reports of the 27th coercing other army troops to kill student protesters.[124] Western media reported that the "27th Army [was] widely hated in Beijing."[122]

There were also reports of standoffs between army units, especially the 27th.[122] The 16th Army was said to be tasked with relieving the 38th, but wanted to do so with minimal force. The 27th, ignoring the 16th's plea, continued on violently towards Tiananmen Square.[125] On June 6, 1989, United States officials confirmed reports involving shootings between the 16th and the 27th armies on the outskirts of Beijing.[41] On June 7, the 38th Army was reportedly in a stand-off with the 27th and the 15th Airborne.[26]

Another unit that rallied against the 27th was the 40th, which established good relations with the civilians along their cordoned area around the airport road. The civilians exchanged food and supplies and offered moral support to the 40th.[122] Although many opposed the undisciplined 27th Army, none was as prominent as the 38th Army.[126] Initially reluctant to obey orders to enter the city, the 38th was replaced by the 27th. However, after June 6 the 38th was sent back into Beijing to relieve the 27th from their occupied posts. Some residents of Beijing welcomed back their beloved troops and regard "The 38th Army [as] the people's army!"[122]

The rumors inspired residents in Shijiazhuang to protest outside the headquarters of the 27th Army.[127] Officers and family members of the 27th were subject to scorn and ridicule in their home city.[127]

In March 1990 a soldier on leave from the 38th army recounted his experience of suppressing the student demonstrations, claiming that his unit was tricked into opening fire on the protesters. During their approach to the square on the night of June 3 the soldier and his unit were unwilling to fire on the crowds blocking their path. They instead fired into the air to frighten protesters, and clear their route to the square. As the soldier's unit marched on, word was passed through the ranks that one hundred of their comrades had gone missing and were presumed to have been killed by the students. A count was conducted, and one hundred soldiers were confirmed missing. The soldiers were saken by this incident, and became enraged with the protestors. Shortly afterwards the order to fire on the crowds was issued and obeyed to devastating effect. After contributing to the successful clearance of the square, the soldier's unit was engaged in cleanup operations. At this time the missing one hundred soldiers reappeared unharmed, having supposedly temporarily deserted their unit. The unidentified soldier had supposedly shared this story with his mother, and the rumor had spread from there, eventually reaching the ears of Pat Wardlaw, the then Consul General of the United States in Shanghai. Wardlaw comments that the source should not be taken a literal fact but instead as an example of the type of rumor circulating in China at the time.[128]

Deng Xiaoping's praise for the Army

[edit]On June 9, Deng Xiaoping made his first public appearance since the beginning of the protests in a speech thanking and praising army's enforcement of martial law.[129] Party organizations organized citizens to study the contents of the speech.[129] He denounced the protests as a counterrevolutionary rebellion to overthrow the party-state, which fully justified the use of force.[129] The demonstrators' complaint about official corruption masked their ulterior motive.[129] The steadfastness of the army, the "great wall of iron and steel" of the party and country, Deng said, had "made it relatively easy" to "handle the present matter".[129] He named 12 soldiers who died in the action "martyrs" and recognized 13 others as "Defenders of the Republic".[6]

Martial law was lifted on January 11, 1990.[6]

Military education and training in China

[edit]After the student movement was suppressed, the State Education Commission of China implemented a year-long military training for the freshmen of Peking University and Fudan University in the military academies.[130][131]

Outcomes for PLA personnel

[edit]Results of Insubordination

[edit]During the Tiananmen repression an estimated 3,500 PLA officers disobeyed orders,[132] In the days after June 4, Western media reported army officers being executed and generals facing court martial,[133] though the executions have not been confirmed. In 1990, the military leadership reshuffled commanders throughout all seven military regions down to the division level to ensure loyalty.[132] There has not been insubordination within the PLA to such an extent in the years since.

General Xu Qinxian of the 38th Army, who refused to enforce martial law, was removed from power, sentenced to five-years imprisonment and expelled from the party. Xu Feng, Commander of the 116th Division, 39th Army, who refused to lead his troops into the city on June 3, was demoted. The entire 28th Army, which refused to obey orders at Muxidi, was ordered to undergo six months of reorganization.[87] General He Yanran, commander of the 28th Army was court-martialed, and along with political commissar Zhang Mingchun and chief of staff Qiu Jinkai, were disciplined, demoted and reassigned to other units.[87]

Promotions

[edit]Military officers who carried out orders vigorously were rewarded with recognition and promotion. Liu Huaqing, the commander of the martial law forces became the vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission in 1990, and eventually gained a seat on the Politburo Standing Committee. Chi Haotian, the deputy commander, became Minister of Defense in 1993. Liang Guanglie, the commander of the 20th Army, who succeeded Chi as the PLA's chief of staff in 1992, eventually ascended to the position of Minister of Defense in 2008. Ai Husheng, who led the 347th Regiment to Tiananmen Square while the rest of the 116th Division under Xu Feng defied martial law orders, enjoyed a series of promotions. Ai took command of the Division in 1995 and then the entire 39th Army in 2002. In 2007, he became chief of staff of the Chengdu Military Region.

Censorship of medals

[edit]In March 2024, censors removed social media posts containing photos of medals awarded to PLA soldiers who participated in the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.[134]

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c Scobell, "Why the People's Army Fired," 201.

- ^ Zhao, D. p. 171

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k (Chinese) Wu Renhua, "戒严部队军警的死亡情况" 《1989天安门事件二十周年祭》 No. 9 Accessed 2013-06-07

- ^ a b c L. Zhang 2001, p. 436.

- ^ a b c Frontline: Memory of Tiananmen 2006.

- ^ a b c d (Chinese) "历程:奉命执行北京市部分地区戒严任务" Xinhua 2005-07-31

- ^ How Many Died 1990.

- ^ U.S. G.P.O., p. 445.

- ^ Brook 1998, p. 154.

- ^ Kristof:Reassessing Casualties.

- ^ Secretary of State's.

- ^ Brook 1998, p. 161.

- ^ a b c d e f g John Garnaut, "How top generals refused to march on Tiananmen Square" Sydney Morning Herald 2010-06-04

- ^ a b Wu 2009, p. 86, 432.

- ^ a b c d Wu 2009, p. 86.

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 15.

- ^ a b Wu 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e Wu 2009, p. 12.

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 17.

- ^ a b Benedict Stavis. "China Explodes at Tiananmen" Asian Affairs, 17; 2. 51–61. Taylor & Francis, Ltd. 1990 (accessed February 17, 2011).

- ^ "PLA Personnel Join Demonstration" Daily Report. Hong Kong HSIN WAN PO in Chinese 17 May 1989.

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 21.

- ^ a b Zhang 2001, p. 265.

- ^ a b Media reports initially estimated troop deployments in the range 100,000 to 150,000. Bernard E. Trainor. "Turmoil in China; Legions of Soldiers Encircling Beijing: Loyalty to Whom?" The New York Times, June 07, 1989 (accessed February 17, 2011).

- ^ (Chinese) "六四抗命将军22年首现身—宁杀头,不作历史罪人" Deutsche Welle 2011-02-16

- ^ (Chinese) "十大王牌军第6位:第12集团军" Archived November 5, 2013, at the Wayback Machine 2007-07-31

- ^ Melissa Roberts. "The Choice: Duty to People or Party" Christian Science Monitor, May 23, 1989 (accessed November 21, 2010).

- ^ a b Wu 2009, p. 95.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 172-73.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 530-31.

- ^ a b James C. Mulvenon and Richard Yang eds. The People's Liberation Army in the Information Age Rand Corporation, 1999, p. 52

- ^ Image of helicopter dropping leaflets over Tiananmen Square

- ^ "Image of helicopter over Tiananmen Square on May 20, 1989

- ^ "SA 342L Gazelle Attack Helicopter" Sinodefence.com Archived 2012-08-23 at the Wayback Machine 2007-06-11

- ^ (Chinese) Wu Renhua, "89天安门事件大事记:5月19日 星期五" Accessed 2013-07-10

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Larry Wortzel, "The Tiananmen Massacre Reappraised: Public Protest, Urban Warfare, and the People's Liberation Army" in Andrew Scobell, Larry M. Wortzel, eds. Chinese National Security Decisionmaking Under Stress pp. 72, 77–78 Diane Publishing, 2005

- ^ a b c d (Chinese) "89天安门事件大事记:5月20日 星期六" Accessed 2013-07-10

- ^ (Chinese) Gallery: "64 存照:八九年六四图片回顾 (中)" 2007-06-03

- ^ a b Trainor, Bernard E.; Times, Special To the New York (June 6, 1989). "Crackdown in Beijin – Civil War For Army?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ^ Geremie Barmé & John Crowley. Gate of heavenly Peace. DVD. Directed by Richard Gordon and Carma Hinton. San Francisco, CA : Distributed by NAATA/CrossCurrent Media, 1997.

- ^ a b c d e "記憶"標準化"的一個實例──解讀"戒嚴一日"的篩選". Archived from the original on February 10, 2006.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 98.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 99.

- ^ a b Wu 2009, pp. 100–101.

- ^ a b Wu 2009, p. 102.

- ^ "Secretary of State's Morning Summary for 3 June 1989". George Washington University (accessed November 19, 2010).

- ^ Zhang 2001, p. 349-353.

- ^ a b c d e f g (Chinese) Wu Renhua, "天安门广场清场命令的下达 " 《1989天安门事件二十周年祭》之五 Accessed 2013-06-30

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j (Chinese) Wu Renhua, "戒严部队的挺进目标和路线" 《1989天安门事件二十周年祭》系列之十三 Accessed 2013-06-30

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 177-179.

- ^ a b Wu 2009, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 304-305.

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 327-331.

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 208.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 209.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 212-13.

- ^ a b Wu 2009, p. 439.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 440.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 439-40.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 441.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 442.

- ^ a b c Nathan 2002, pp. 489.

- ^ a b c d e f Nathan, Andrew J.; Link, Perry; Liang, Zhang (2002). "The Tiananmen Papers". Foreign Affairs. 80 (1): 2–48. doi:10.2307/20050041. JSTOR 20050041. Retrieved July 4, 2023.

- ^ Brown, Jeremy (2021). June Forth: The Tiananmen Protests and Beijing Massacre of 1989. Cambridge University Press. p. 112. ISBN 978-1107657809.

- ^ a b Thomas 2006.

- ^ a b John Pomfret interview 2006.

- ^ Nathan 2002, pp. 492.

- ^ a b Nathan 2002, pp. 493.

- ^ a b c d Timothy Brook interview 2006.

- ^ a b Baum 1996, p. 283.

- ^ a b c Lim 2014a, p. 38.

- ^ Richelson & Evans 1999b.

- ^ Martel 2006.

- ^ a b Berry 2008, pp. 302–3.

- ^ Lim 2014a, p. 16.

- ^ a b Brook 1998, p. 130.

- ^ Berry 2008, p. 303.

- ^ Lim 2014a, pp. 16–17.

- ^ "14-August 15 1989" (PDF). The George Washington University.

- ^ a b (Chinese) Wu Renhua, "89天安门事件大事记:6月4日 星期日" Accessed 2013-07-02

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q (Chinese) Wu Renhua, "吴仁华:六四事件中的坦克第一师" DWnews.com Archived December 17, 2013, at the Wayback Machine 2013-06-04

- ^ a b c d e f g h (Chinese) Fang Bing, "参与六四镇压军官公开事件真相" Voice of America 2002-05-30

- ^ (Chinese) Wu Renhua, "天安门事件的最后一幕" Accessed 2013-07-02

- ^ 张东旭, "推倒‘女神'像" in 总政文化部征文办公室编, 《戒严一日》 (1989) pp. 259–62

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j (Chinese) 英年早逝的'六四'抗命将领张明春少将 Archived 2013-12-19 at the Wayback Machine 2011-01-17

- ^ a b c d e f Thomas 2006, 32:23–34:50.

- ^ "Interview with Jan Wong". PBS. April 11, 2006. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- ^ Karl Schoenberger, "8 Sentenced to Die in Beijing Fighting: Are Convicted of Beating Soldiers, Burning Vehicles" L.A. Times, 1989-06-18

- ^ a b c Wu 2009, p. 534.

- ^ Wu 2009, p. 534-35.

- ^ "Picture Power:Tiananmen Standoff". BBC News. Retrieved October 7, 2005.

- ^ Jan, Wong. "Jan Wong, August 1988 – August 1994". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved July 9, 2023.

- ^ Kristof, Nicholas D. (June 8, 1989). "TURMOIL IN CHINA; FOREBODING GRASPS BEIJING; ARMY UNITS CRISSCROSS CITY; FOREIGNERS HURRY TO LEAVE". The New York Times. New York Times. Retrieved July 3, 2023.

- ^ .1. Scobell, Andrew. "Why the People's Army Fired on the People: The Chinese Military and Tiananmen." Armed Forces & Society 18, no. 2 (1992): 193–213.

- ^ 3. Secretary of State's Morning Summary for June 6, 1989, China: Descent into Chaos, June 6, 1989. Tiananmen Square 1989: The Declassified History, George Washington University Archives. (accessed March 26, 2018) https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu //NSAEBB/NSAEBB16/docs/doc 19.pdf

- ^ Scobell, "Why the People's Army Fired," 199.

- ^ a b c d Scobell, "Why the People's Army Fired," 200.

- ^ Lim, Louisa. The People's Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited. Oxford University Press, USA, 2014.

- ^ Lim, "The People's Republic of Amnesia," 11.

- ^ Lim, "The People's Republic of Amnesia," 11.

- ^ Lim, "The People's Republic of Amnesia," 12.

- ^ Lim, "The People's Republic of Amnesia," 13.

- ^ Lim, "The People's Republic of Amnesia," 13.

- ^ Zhang, Liang, Andrew J. Nathan, Perry Link, and Orville Schell. The Tiananmen papers. PublicAffairs, 2008. 321.

- ^ a b The Tiananmen Papers., 321.

- ^ 14. Cable, From: Department of State, Wash DC, To: U.S. Embassy Beijing, and All Diplomatic and Consular Posts, TFCHO1: SITREP 1, 1700 EDT, June 3, 1989. Tiananmen Square 1989: The Declassified History, George Washington University Archives. (accessed March 26, 2018). https://nsarchive2.gwu.edu/NSAEBB/NSAEBB47/doc12.pdf

- ^ The Tiananmen Papers., 349.

- ^ The Tiananmen Papers., 388.

- ^ Southerl, Daniel. "Chinese Army Units Seen Near Conflict." Washington Post, June 6, 1989. Accessed March 27, 2018. [1][dead link] /1989/06/06/chinese-army-units-seen-near-conflict/d6c31719-c4ef-49b5-b6db-0f87d48b5dfa/

- ^ a b c d "Secretary of State's Morning Summary," 27.

- ^ a b c d e Southerl, "Chinese Army Units."

- ^ Why the People's Army Fired. p. 204. JSTOR 45305304. Retrieved June 24, 2023.

- ^ Lim, "The People's Republic of Amnesia," 21.

- ^ Li, Xiaoming. "An Officer's Memories of Martial Law in 1989." Interview by Yu Wang. Human Rights in China, February 16, 2003. https://www.hrichina.org /en/content/4772

- ^ a b c d Li, "An Officer's Memories."

- ^ "Secretary of State's Morning Summary," 21.

- ^ a b Wu 2009, p. 62.

- ^ Ming Pao. "Reports Indiscriminate Killing, Some Troops Refusing to Obey Orders" BBC Summary of the World Broadcasts, June 6, 1989. http://www.lexisnexis.com (accessed November 21, 2010).

- ^ NICHOLA D. KRISTOF, "China Whispers of Plots and Man Called Yang" N.Y. Times Oct. 24, 1989

- ^ a b c d e Daniel Southerland & John Burgess. "Residents in Beijing Welcome Some Troops" The Washington Post, June 7, 1989.

- ^ Michael Browning. "Signs of Serious Rifts in the People's Army" The Advertiser, June 6, 1989. http://www.lexisnexis.com (accessed November 21, 2010).

- ^ Jan Wong. "Army that cleared Tiananmen killed rival troops, sources say." The Globe and Mail, June 8, 1989.

- ^ "China believed close to civil war; Troops reported battling each other, Li said to have survived murder bid: [EARLY Edition 1]." The Gazette, June 6, 1989.

- ^ "Chinese troops open fire again: Report has army split :[FINAL Edition]." The Windsor Star, June 5, 1989.

- ^ a b (Chinese) Lin Bin, "8964大屠杀 二十八军抗命" 2009-06-02

- ^ Wardlaw, "Blood and Bitterness: A Soldier's Tale of Tiananmen", (WikiLeaks, WikiLeaks cable), accessed April 3, 2016, https://wikileaks.org/plusd/cables/90SHANGHAI2272_a.html

- ^ a b c d e "Deng's June 9 Speech: 'We Faced a Rebellious Clique' and 'Dregs of Society'". New York Times. June 30, 1989. Retrieved May 1, 2012.

- ^ "Second Chinese College Sends Freshmen for Year of Army Training". Associated Press. September 21, 1990. Archived from the original on June 2, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2012.

- ^ Wudunn, Sheryl (August 15, 1989). "Chinese College Freshmen to Join Army First". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 16, 2014. Retrieved September 29, 2012.

- ^ a b Chong-Pin Lin. "China's Restive Army". Wall Street Journal, Oct 09 1991.

- ^ "Officers who refused to halt protests executed :[Final Edition]." The Gazette, June 12, 1989.

- ^ "Chinese censors remove video showing off Tiananmen massacre medal". Radio Free Asia. March 21, 2024. Retrieved March 24, 2024.

Sources

[edit]- Baum, Richard (1996). Burying Mao: Chinese Politics in the Age of Deng Xiaoping. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691036373. Archived from the original on July 10, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- "Interview with John Pomfret". Frontline. PBS. April 11, 2006. Archived from the original on September 21, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- "Interview with Timothy Brook". Frontline. PBS. April 11, 2006. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2009.

- Lim, Louisa (2014). The People's Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0199347704. Archived from the original on July 19, 2020. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- Martel, Ed (April 11, 2006). "'The Tank Man,' a 'Frontline' Documentary, Examines One Man's Act in Tiananmen Square". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2019. Retrieved March 16, 2019.

- Nathan, Andrew (2002). "On the Tiananmen Papers". Foreign Affairs. 80 (1): 2–48. doi:10.2307/20050041. JSTOR 20050041.

- Richelson, Jeffrey T.; Evans, Michael L., eds. (June 1, 1999). "Tiananmen Square, 1989: The Declassified History – Document 13: Secretary of State's Morning Summary for June 4, 1989, China: Troops Open Fire" (PDF). National Security Archive. George Washington University. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- Wu, Renhua (2009). 六四事件中的戒严部队 [Military Units Enforcing Martial Law During the June 4 Incident] (in Chinese). Hong Kong: 真相出版社. ISBN 978-0-9823203-8-9. Archived from the original on October 17, 2007. Retrieved July 16, 2013.

- Zhang, Liang (2001). Nathan, Andrew; Link, Perry (eds.). The Tiananmen Papers. Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-122-3.

- "How Many Really Died? Tiananmen Square Fatalities". Time. June 4, 1990.

- United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Foreign Relations. Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs (1991). Sino-American relations: One year after the massacre at Tiananmen Square. U.S. G.P.O.

- Brook, Timothy (1998). Quelling the People: The Military Suppression of the Beijing Democracy Movement. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-3638-1.

- "Secretary of State's Morning Summary for 3 June 1989". George Washington University. Retrieved August 4, 2008.

- Kristof, Nicholas D. (June 21, 1989). "A Reassessment of How Many Died in the Military Crackdown in Beijing". The New York Times.

- "The Memory Of Tiananmen – The Tank Man". www.pbs.org. Frontline – PBS.

- Thomas, Antony (2006). The Tank Man (Video). PBS. Retrieved July 2, 2013.

- Zhang, Liang (2001). Nathan, Andrew; Link, Perry (eds.). The Tiananmen Papers: The Chinese Leadership's Decision to Use Force, in Their Own Words. Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-122-3.

- Berry, Michael (2008). A History of Pain: Trauma in Modern Chinese Literature and Film. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231512008.