Russia–NATO relations

| |

NATO |

Russia |

|---|---|

Relations between the NATO military alliance and the Russian Federation were established in 1991 within the framework of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council. In 1994, Russia joined the Partnership for Peace program, and on 27 May 1997, the NATO–Russia Founding Act (NRFA) was signed at the 1997 Paris NATO Summit in France, enabling the creation of the NATO–Russia Permanent Joint Council (NRPJC). Through the early part of 2010s NATO and Russia signed several additional agreements on cooperation.[1] The NRPJC was replaced in 2002 by the NATO–Russia Council (NRC), which was established in an effort to partner on security issues and joint projects together.

Despite efforts to structure forums that promote cooperation between Russia and NATO, relations as of 2024 have become severely strained over time due to post-Soviet conflicts and territory disputes involving Russia having broken out, including:

- Azerbaijan (1988–2024)[2][3][4]

- Moldova (1990–present)[5]

- Georgia (2008–present)[6]

- Ukraine (2014–present)[7][8]

- Syria (2015–present)[9]

- Turkey (2015–2016)

- Kazakhstan (2021–2022)[10]

Russia–NATO relations started to substantially deteriorate following the Ukrainian Orange Revolution in 2004–05 and the Russo-Georgian War in 2008. They deteriorated even further in 2014, when on 1 April 2014, NATO unanimously decided to suspend all practical co-operation as a response to the Russian annexation of Crimea. In October 2021, following an incident in which NATO expelled eight Russian officials from its Brussels headquarters, Russia suspended its mission to NATO and ordered the closure of the NATO office in Moscow.[11][12]

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 has caused a breakdown of NATO–Russia relationships to the lowest point since the end of the Cold War in 1991. The 2022 NATO Madrid summit declared Russia "a direct threat to Euro-Atlantic security" while the NATO–Russia Council was declared defunct.[13] Although Russian officials and propagandists have claimed that they are "at war" with the whole of NATO and the West, NATO has maintained that its focus is on helping Ukraine defend itself, and not on fighting Russia.[14][15]

Background[edit]

Following the Treaty on the Final Settlement with Respect to Germany which dissolved the Allied Control Council, NATO and the Soviet Union began to engage in talks on several levels, including a continued push for arms control treaties such as the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe. Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze made a first visit to NATO Headquarters on 19 December 1989, followed by informal talks in 1990 between NATO and Soviet military leaders.[16]

After the fall of the Soviet Union, there were conversations regarding the NATO's role in the changing security landscape in Europe, with U.S. President George H.W. Bush, U.S. Secretary of State James Baker, West German chancellor Helmut Kohl, West German foreign minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher, and Douglas Hurd, the British foreign minister. The West German foreign minister, Hans-Dietrich Genscher, in a meeting on February 6, 1990, suggested the alliance should issue a public statement saying that, "NATO does not intend to expand its territory to the East."[17]

Development of post-Cold War cooperation (1990–2004)[edit]

In June 1990 the Message from Turnberry, often described as "the first step in the evolution of [modern] NATO-Russia relations", laid the foundation for future peace and cooperation.[18] The following month, NATO Secretary General, Manfred Wörner, visited Moscow in July 1990 to discuss future cooperation.[19]

According to several news reports and memoirs of politicians, in 1990, during negotiations about German unification, the administration of then-US President George H.W. Bush made a ‘categorical assurance’ to the then-President of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev: If Gorbachev agreed that a reunified Germany was part of NATO, then NATO would not enlarge further east to incorporate former Warsaw Pact countries in the alliance. The rationale was to allow for ‘a non-aligned buffer zone’ between the Russian border and that of the NATO states.[20] Gorbachev denied those claims and stated that the promise from NATO not to enlarge eastward is a myth. He also said, "The decision for the U.S. and its allies to expand NATO into the east was decisively made in 1993. I called this a big mistake from the very beginning. It was definitely a violation of the spirit of the statements and assurances made to us in 1990."[21]

In 1990, the Soviet Union and the western countries signed the Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe. Formal contacts and cooperation between the newly founded Russian Federation and NATO began following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, within the framework of the North Atlantic Cooperation Council (later renamed Euro-Atlantic Partnership Council), and were further deepened as Russia joined the Partnership for Peace program on 22 June 1994.[22][23][24][25]

In 1990–91, Western policy makers did indeed operate on a premise that NATO had no purpose in expanding to Eastern Europe, and that such a move would badly hurt long-term prospects for stability and security in Russia and Eastern Europe.[26] However, the commitment to not expand NATO into Poland and further countries existed only briefly. In 1992, i.e. only a few months after the USSR disintergrated, the US intention to invite former Warsaw Pact countries into NATO firmed up.[27]

In 1994, the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), an alternative Russian-led military alliance of Post-Soviet states, was founded.

Budapest Memorandum[edit]

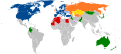

NPT-designated nuclear weapon states (China, France, Russia, United Kingdom, United States)

Other states with nuclear weapons (India, North Korea, Pakistan) Other states presumed to have nuclear weapons (Israel)

NATO member nuclear weapons sharing states (Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey)

States formerly possessing nuclear weapons (Belarus, Kazakhstan, South Africa, Ukraine)

Nuclear weapons were deployed in the past also to Canada, Cuba, Cyprus, Czechoslovakia, Denmark, Greece, Hungary, Mongolia, Morocco, the Philippines, Poland, Singapore, South Korea, Spain, and Taiwan

In the same year, the Budapest Memorandum was signed where Russia, the United Kingdom and the United States made security assurances to Belarus, Kazakhstan and Ukraine, in return for handing over by these three countries of their post-Soviet nuclear arsenal. [citation needed]

NATO–Russia Founding Act[edit]

On 27 May 1997, at the NATO Summit in Paris, France, NATO and Russia signed the Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security, a road map for would-be NATO-Russia cooperation.[28][29][30] The act had 5 main sections, outlining the principles of the relationship, the range of issues NATO and Russia would discuss, the military dimensions of the relationship, and the mechanisms to foster greater military-military cooperation.

NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council[edit]

Additionally, the act established a forum called the "NATO-Russia Permanent Joint Council" (NRPJC) as a venue for consultations, cooperation and consensus building.[31] As part of the efforts of the PJC, the NATO-Russia Glossary of Contemporary Political and Military Terms was created in 2001.[32] The glossary was the first of several such publications on topics such as missile defense, demilitarization, and countering illicit drugs to encourage transparency in NATO-Russia Relations, foster mutual understanding, and facilitate communication between NATO and Russia contingents.[33]

The Glossary of Contemporary Political and Military Terms was especially timely given the NATO and Russia cooperative efforts in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo.[32][34]

NATO bombing of Yugoslavia[edit]

In 1999, Russia condemned the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia,[35][36] which was done without a prior authorization by the United Nations Security Council, required by the international law.[37] For many in Moscow, a combination of NATO’s incorporation of Eastern Europe and its military attack on sovereign Yugoslavia exposed American promises of Russia’s inclusion into a new European security architecture as a deceit. Yeltsin’s critics said: ‘Belgrade today, Moscow tomorrow!’ [38]

Russian President Boris Yeltsin said that NATO's bombing of Yugoslavia "has trampled upon the foundations of international law and the United Nations charter."[39] The Kosovo War ended on 11 June 1999, and a joint NATO-Russian peacekeeping force was to be installed in Kosovo. Russia had expected to receive a peacekeeping sector independent of NATO, and was angered when this was refused. There was concern that a separate Russian sector might lead to a partition of Kosovo between a Serb-controlled north and Albanian south.[40] From 12 to 26 June 1999, there was a brief but tense stand-off between NATO and the Russian Kosovo Force in which Russian troops occupied the Pristina International Airport.[41][42]

NATO-Russia Council[edit]

In 2000 Putin told George Robertson, the Secretary General of NATO at that time, that he wanted Russia to join NATO but would not like to go through the usual application process.[43]

In 2001, following the September 11 attacks against the United States, Russian President Vladimir Putin reached out to President George W. Bush, the President of the United States at the time. This was the height of U.S.-Russian relations since the end of the Cold War. Russia even shared intelligence that they had with the United States, which proved vital to the U.S. forces in Afghanistan.[citation needed] As a member of NATO, the United States' newly positive relationship with Russia would positively impact Russian-NATO relations.[44]

The NATO-Russia Council (NRC) was created on 28 May 2002 during the 2002 NATO Summit in Rome. The NRC was designed to replace the PJC as the official diplomatic tool for handling security issues and joint projects between NATO and Russia.[45] The structure of the NRC provided that the individual member states and Russia were each equal partners and would meet in areas of common interest, instead of the bilateral format (NATO + 1) established under the PJC.[46] There was no provision granting NATO or Russia any veto powers over the actions of the other. NATO said it had no plans to station nuclear weapons in the new member states or send in new permanent military forces. The parties stated they did not see each other as adversaries, and, "based on an enduring political commitment undertaken at the highest political level, will build together a lasting and inclusive peace in the Euro-Atlantic area on the principles of democracy and cooperative security".[47]

Cooperation between Russia and NATO focused on several main sectors: terrorism, military cooperation, Afghanistan (including transportation by Russia of non-military International Security Assistance Force freight (see NATO logistics in the Afghan War), and fighting local drug production), industrial cooperation, and weapons non-proliferation.[48] As a result of its structured working groups across a range of areas, the NRC served as the primary forum for consensus-building, cooperation, and consultation on topics such as terrorism, proliferation, peacekeeping, airspace management, and missile defense.[46][49]

"Joint decisions and actions", taken under NATO-Russia Council agreements, include:

- Fighting terrorism[50][51]

- Military cooperation (joint military exercises[52] and personnel training[53])

- Cooperation on Afghanistan:

- Russia providing training courses for anti-narcotics officers from Afghanistan and Central Asia countries in cooperation with the UN

- Transportation by Russia of non-military freight in support of NATO's ISAF in Afghanistan, industrial cooperation, cooperation on defence interoperability, non-proliferation, and other areas.

Reversal of the US policy in 2001[edit]

A drastic reversion of the US and NATO policy toward Russia occurred in 2001 under George W. Bush. Most importantly, the US unilaterally withdrew from the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with Russia in 2001–2002, which was followed by US signing bilateral agreements with Poland and Romania (with NATO support) to build ballistic missile defense (BMD) systems on their territories against Russian wishes. Although none of these events depended on NATO enlargement - not even the agreement to build BMD sites in Romania and Poland, given that the United States also has bilateral BMD equipment arrangements with a wide variety of non-NATO members (including Bahrain, Egypt, Israel, Japan, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, South Korea, Taiwan, and the United Arab Emirates) this withdrawal was interpreted by Russian political elite and by many Western political scientists, as a sign of USA exploiting political and military weakness of Russia at that time, and lead to the loss of Russia's trust into US political intentions.[54]

Stagnation and gradual deterioration of relations (2004–2013)[edit]

NATO–Russia relations stalled and subsequently started to deteriorate, following the Ukrainian Orange Revolution in 2004–2005 and the Russo-Georgian War in 2008.

2004–2007[edit]

In the years 2004–2006, Russia undertook several hostile trade actions directed against Ukraine and the Western countries (see #Trade and economy below). Several highly publicised murders of Putin's opponents also occurred in Russia in that period, marking his increasingly authoritarian rule and the tightening of his grip on the media (see #Ideology and propaganda below).

In 2006, Russian intelligence performed an assassination on the territory of a NATO member state.[citation needed] On 1 November 2006, Alexander Litvinenko, a British-naturalised Russian defector and former officer of the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) who specialised in tackling organized crime and advised British intelligence and coined the term "mafia state", suddenly fell ill and was hospitalised after poisoning with polonium-210; he died from the poisoning on 23 November.[55] The events leading up to this are well documented, despite spawning numerous theories relating to his poisoning and death. A British murder investigation identified Andrey Lugovoy, a former member of Russia's Federal Protective Service (FSO), as the main suspect. Dmitry Kovtun was later named as a second suspect.[56] The United Kingdom demanded that Lugovoy be extradited, however Russia denied the extradition as the Russian constitution prohibits the extradition of Russian citizens, leading to a straining of relations between Russia and the United Kingdom.[57]

Subsequently, Russia suspended in 2007 its participation in the 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe.

2008[edit]

In 2008, Russia condemned the unilateral declaration of independence of Kosovo,[58] stating they "expect the UN mission and NATO-led forces in Kosovo to take immediate action to carry out their mandate ... including the annulling of the decisions of Pristina's self-governing organs and the taking of tough administrative measures against them."[59] Russian President Vladimir Putin described the recognition of Kosovo's independence by several major world powers as "a terrible precedent, which will de facto blow apart the whole system of international relations, developed not over decades, but over centuries", and that "they have not thought through the results of what they are doing. At the end of the day it is a two-ended stick and the second end will come back and hit them in the face".[60] Europe was not unanimous in this matter, and a number of European countries have refused to recognise the sovereignty of Kosovo, while a number of further European nations did so only to appease the United States.[citation needed]

Nevertheless, the heads of state for NATO Allies and Russia gave a positive assessment of NATO-Russia Council achievements in a Bucharest summit meeting in April 2008,[61] though both sides have expressed mild discontent with the lack of actual content resulting from the council.

In early 2008, U.S. President George W. Bush vowed full support for admitting Georgia and Ukraine into NATO, to the opposition of Russia.[62][63] The Russian Government claimed plans to expand NATO to Ukraine and Georgia may negatively affect European security. Likewise, Russians are mostly strongly opposed to any eastward expansion of NATO.[64][65] Russian President Dmitry Medvedev stated in 2008 that "no country would be happy about a military bloc to which it did not belong approaching its borders".[66] Russia's Deputy Foreign Minister Grigory Karasin warned that any incorporation of Ukraine into NATO would cause a "deep crisis" in Russia–Ukraine relations and also negatively affect Russia's relations with the West.[67]

Relations between NATO and Russia soured in summer 2008 due to Russia's war with Georgia. Later the North Atlantic Council condemned Russia for recognizing the South Ossetia and Abkhazia regions of Georgia as independent states.[68] The Secretary General of NATO claimed that Russia's recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia violated numerous UN Security Council resolutions, including resolutions endorsed by Russia. Russia, in turn, insisted the recognition was taken basing on the situation on the ground, and was in line with the UN Charter, the CSCE Helsinki Final Act of 1975 and other fundamental international law;[69] Russian media heavily stressed the precedent of the recent Kosovo declaration of independence.

2009[edit]

In January 2009, the Russian envoy to NATO Dmitry Rogozin said the NATO-Russia council was "a body where scholastic discussions were held." A US official shared this view, stating: "We want now to structure cooperation more practically, in areas where you can achieve results, instead of insisting on things that won't happen."[70]

Relations were further strained in May 2009 when NATO expelled two Russian diplomats over accusations of espionage. It has also added to the tension already created by proposed NATO military exercises in Georgia, as the Russian President Dmitry Medvedev said,

The planned NATO exercises in Georgia, no matter how one tries to convince us otherwise, are an overt provocation. One cannot carry out exercises in a place where there was just a war.[71]

In September 2009, the Russian Government said that United States proposed missile defence system in Poland and in the Czech Republic could threaten its own defences. The Russian Space Forces commander, Colonel General Vladimir Popovkin stated in 2007 that "[the] trajectories of Iranian or North Korean missiles would hardly pass anywhere near the territory of the Czech republic, but every possible launch of Russian ICBM from the territory of the European Russia, or made by Russian Northern Fleet would be controlled by the [radar] station".[72][73] However, later in 2009, Barack Obama canceled the missile defence project in Poland and the Czech Republic after Russia threatened the US with military response, and warned Poland that by agreeing to NATO's anti-missile system, it was exposing itself to a strike or nuclear attack from Russia.[73]

In December 2009, NATO approached Russia for help in Afghanistan, requesting permission for the alliance to fly cargo (including possibly military ones) over Russian territory to Afghanistan and to provide more helicopters for the Afghan armed forces.[74] However Russia only allowed transit of non-military supplies through its territory.[75]

2010[edit]

Before the Russian Parliamentary elections in 2011, President Dmitry Medvedev was also quoted as saying that had Russia not joined the 2008 South Ossetia war, NATO would have expanded further eastward.[76]

2011[edit]

On 6 June 2011, NATO and Russia participated in their first ever joint fighter jet exercise, dubbed "Vigilant Skies 2011". Since the Cold War, this is only the second joint military venture between the alliance and Russia, with the first being a joint submarine exercise which begun on 30 May 2011.[77]

The 2011 military intervention in Libya prompted a widespread wave of criticism from several world leaders, including Russian President Dmitry Medvedev[78] and Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, who said that "[UNSC Resolution 1973] is defective and flawed...It allows everything. It resembles medieval calls for crusades."[79]

2012–2013[edit]

In April 2012, there were some protests in Russia over their country's involvement with NATO, conducted by the leftist activist alliance Left Front.[80]

Rising tensions, suspension of cooperation, sanctions (2014–2021)[edit]

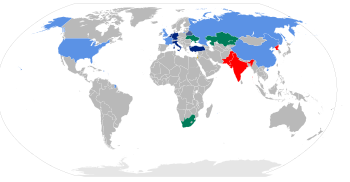

NATO member states

States affected by territorial conflicts with the involvement of Russia (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Japan, Moldova and Ukraine)

Disputed regions either unilaterally declared as annexed by Russia into its territory (Crimea, Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia and the Kuril Islands), recognized as sovereign states (Abkhazia and South Ossetia) or supported as separatist regions (Transnistria, Artsakh)

Beginning in 2014, Russia engaged in further hostile threats followed by military actions against Ukraine (2014–present); Syria (2015–present), and Turkey (2015–2016), among others.[4]

2014[edit]

In early March 2014, tensions increased between NATO and Russia as a result of Russia's move to annex Crimea: NATO urged Russia to stop its actions and said it supported Ukraine's territorial integrity and sovereignty.[81] On 1 April 2014, NATO issued a statement by NATO foreign ministers that announced it had "decided to suspend all practical civilian and military cooperation between NATO and Russia. Our political dialogue in the NATO-Russia Council can continue, as necessary, at the Ambassadorial level and above, to allow us to exchange views, first and foremost on this crisis".[82][83] The statement condemned Russia's "illegal military intervention in Ukraine and Russia's violation of Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity".[83] Russia used Kosovo's declaration of independence as a justification for recognizing the independence of Crimea, citing the so-called "Kosovo independence precedent".[84][85]

On 25 March 2014, Jens Stoltenberg gave a speech to a Norwegian Labour Party convention where he harshly criticized Russia over its invasion of Crimea, stating that Russia threatened security and stability in Europe and violated international law, and calling Russia's actions unacceptable.[86] After his election as NATO Secretary-General, Stoltenberg emphasized that Russia's invasion of Ukraine was a "brutal reminder of the necessity of NATO," stating that Russia's actions in Ukraine represented "the first time since the Second World War that a country has annexed a territory belonging to another country."[87] Stoltenberg has highlighted the necessity of NATO having a sufficiently strong military capacity, including nuclear weapons, to deter Russia from violating international law and threaten the security of NATO's member states. He has highlighted the importance of Article 5 in the North Atlantic Treaty and NATO's responsibility to defend the security of its eastern members in particular. He has further stated that Russia needs to be sanctioned over its actions in Ukraine, and has said that a possible NATO membership of Ukraine will be "a very important question" in the near future. Stoltenberg has expressed concern over Russia acquiring new cruise missiles.[88]

On 1 April 2014, NATO unanimously decided to suspend all practical co-operation with the Russian Federation in response to the Annexation of Crimea, but the NATO-Russia Council (NRC) was not suspended.[89] At the NATO Wales summit in early September, the NATO-Ukraine Commission adopted a Joint Statement that "strongly condemned Russia's illegal and illegitimate self-declared "annexation" of Crimea and its continued and deliberate destabilization of eastern Ukraine in violation of international law";[90] This position was re-affirmed in the early December statement by the same body.[91]

A report released in November highlighted the fact that close military encounters between Russia and the West (mainly NATO countries) had jumped to Cold War levels, with 40 dangerous or sensitive incidents recorded in the eight months alone, including a near-collision between a Russian reconnaissance plane and a passenger plane taking off from Denmark in March with 132 passengers on board.[92] An unprecedented increase[93] in Russian air force and naval activity in the Baltic region prompted NATO to step up its longstanding rotation of military jets in Lithuania.[94] Similar Russian air force increased activity in the Asia-Pacific region that relied on the resumed use of the previously abandoned Soviet military base at Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam.[95] In March 2015, Russia's defense minister Sergey Shoygu said that Russia's long-range bombers would continue patrolling various parts of the world and expand into other regions.[96]

In July, the U.S. formally accused Russia of having violated the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty by testing a prohibited medium-range ground-launched cruise missile (presumably R-500,[97] a modification of Iskander)[98] and threatened to retaliate accordingly.[98][99] In early June 2015, the U.S. State Department reported that Russia had failed to correct the violation of the I.N.F. Treaty; the U.S. government was said to have made no discernible headway in making Russia so much as acknowledge the compliance problem.[100]

The US government's October 2014 report claimed that Russia had 1,643 nuclear warheads ready to launch (an increase from 1,537 in 2011) – one more than the US, thus overtaking the US for the first time since 2000; both countries' deployed capacity being in violation of the 2010 New START treaty that sets a cap of 1,550 nuclear warheads.[101] Likewise, even before 2014, the US had set about implementing a large-scale program, worth up to a trillion dollars, aimed at overall revitalization of its atomic energy industry, which includes plans for a new generation of weapon carriers and construction of such sites as the Chemistry and Metallurgy Research Replacement Facility in Los Alamos, New Mexico and the National Security Campus in south Kansas City.[102][103]

At the end of 2014, Putin approved a revised national military doctrine, which listed NATO's military buildup near the Russian borders as the top military threat.[104][105]

On 2 December 2014, NATO foreign ministers announced an interim Spearhead Force (the 'Very High Readiness Joint Task Force') created pursuant to the Readiness Action Plan agreed on at the NATO Wales summit in early September 2014 and meant to enhance NATO presence in the eastern part of the alliance.[106][107] In June 2015, in the course of military drills held in Poland, NATO tested the new rapid reaction force for the first time, with more than 2,000 troops from nine states taking part in the exercise.[108][109]

2015[edit]

Stoltenberg has called for more cooperation with Russia in the fight against terrorism following the deadly January 2015 attack on the headquarters of a French satirical weekly magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris.[110]

In early February 2015, NATO diplomats said that concern was growing in NATO over Russia's nuclear strategy and indications that Russia's nuclear strategy appeared to point to a lowering of the threshold for using nuclear weapons in any conflict.[111] The conclusion was followed by British Defense Secretary Michael Fallon saying that Britain must update its nuclear arsenal in response to Russian modernization of its nuclear forces.[112] Later in February, Fallon said that Putin could repeat tactics used in Ukraine in Baltic members of the NATO alliance; he also said: "NATO has to be ready for any kind of aggression from Russia, whatever form it takes. NATO is getting ready."[113] Fallon noted that it was not a new Cold War with Russia, as the situation was already "pretty warm".[113]

In March 2015, Russia, citing NATO's de facto breach of the 1990 Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe, said that the suspension of its participation in it, announced in 2007, was now "complete" through halting its participation in the consulting group on the Treaty.[114][115]

In spring, the Russian Defense Ministry announced it was planning to deploy additional forces in Crimea as part of beefing up its Black Sea Fleet, including re-deployment by 2016 of nuclear-capable Tupolev Tu-22M3 ('Backfire') long-range strike bombers—which used to be the backbone of Soviet naval strike units during the Cold War, but were later withdrawn from bases in Crimea.[116] Early April 2015 saw the publication of the leaked information ascribed to semi-official sources within the Russian military and intelligence establishment, about Russia's alleged preparedness for a nuclear response to certain inimical non-nuclear acts on the part of NATO; such implied threats were interpreted as "an attempt to create strategic uncertainty" and undermine Western political cohesion.[117] Also in this vein, Norway's defense minister, Ine Eriksen Søreide, noted that Russia had "created uncertainty about its intentions".[118]

In June 2015, an independent Russian military analyst was quoted by a major American newspaper as saying: "Everybody should understand that we are living in a totally different world than two years ago. In that world, which we lost, it was possible to organize your security with treaties, with mutual-trust measures. Now we have come to an absolutely different situation, where the general way to ensure your security is military deterrence."[119]

On 16 June 2015, Tass quoted Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Aleksey Meshkov as saying that "none of the Russia-NATO programs that used to be at work are functioning at a working level."[120]

In late June 2015, while on a trip to Estonia, US Defence Secretary Ashton Carter said the US would deploy heavy weapons, including tanks, armoured vehicles and artillery, in Bulgaria, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania.[121] The move was interpreted by Western commentators as marking the beginning of a reorientation of NATO's strategy.[122] It was called by a senior Russian Defence Ministry official "the most aggressive act by Washington since the Cold War"[123] and criticised by the Russian Foreign Ministry as "inadequate in military terms" and "an obvious return by the United States and its allies to the schemes of 'the Cold War'".[124]

On its part, the U.S. expressed concern over Putin's announcement of plans to add over 40 new ballistic missiles to Russia's nuclear weapons arsenal in 2015.[123] American observers and analysts, such as Steven Pifer, noting that the U.S. had no reason for alarm about the new missiles, provided that Russia remained within the limits of the 2010 New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (New START), viewed the ratcheting-up of nuclear saber-rattling by Russia's leadership as mainly bluff and bluster designed to conceal Russia's weaknesses;[125] however, Pifer suggested that the most alarming motivation behind this rhetoric could be Putin seeing nuclear weapons not merely as tools of deterrence, but as tools of coercion.[126]

Meanwhile, at the end of June 2015, it was reported that the production schedule for a new Russian MIRV-equipped, super-heavy thermonuclear intercontinental ballistic missile Sarmat, intended to replace the obsolete Soviet-era SS-18 Satan missiles, was slipping.[127] Also noted by commentators were the inevitable financial and technological constraints that would hamper any real arms race with the West, if such course were to be embarked on by Russia.[119]

Under the Stoltenberg leadership, NATO took a radically new position on propaganda and counter-propaganda in 2015, that "Entirely legal activities, such as running a pro-Moscow TV station, could become a broader assault on a country that would require a NATO response under Article Five of the Treaty... A final strategy is expected in October 2015."[128] In another report, the journalist reported that "as part of the hardened stance, Britain has committed £750,000 of UK money to support a counter-propaganda unit at NATO's headquarters in Brussels."[129]

In November NATO's top military commander US General Philip Breedlove said that the alliance was "watching for indications" amid fears over the possibility that Russia could move any of its nuclear arsenal to the peninsula.[130]

NATO-Russia tensions rose further after, on 24 November 2015, Turkey shot down a Russian warplane that allegedly violated Turkish airspace while on a mission in northwestern Syria.[131] Russian officials denied that the plane had entered Turkish airspace. Shortly after the incident, NATO called an emergency meeting to discuss the matter. Stoltenberg said "We stand in solidarity with Turkey and support the territorial integrity of our NATO ally" after Turkey shot down a Russian military jet for allegedly violating Turkish airspace for 17 seconds, near the Syrian border.[132]

On 2 December 2015, NATO member states formally invited Montenegro to join the alliance, which drew a response from Russia that it would suspend cooperation with that country.[133]

In December, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said re-deployment of nuclear-capable Tupolev Tu-22M3 ('Backfire') long-range strike bombers to Crimea would be a legitimate action as "Crimea has now become part of a country that has such weapons under the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons."[134]

2016[edit]

Shortly before a meeting of the NATO–Russia Council at the level of permanent representatives on 20 April, the first such meeting since June 2014,[135] Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov cited what he saw as "an unprecedented military buildup since the end of the Cold War and the presence of NATO on the so-called eastern flank of the alliance with the goal of exerting military and political pressure on Russia for containing it", and said "Russia does not plan and will not be drawn into a senseless confrontation and is convinced that there is no reasonable alternative to mutually beneficial all-European cooperation in security sphere based on the principle of indivisibility of security relying on the international law."[136][137] Russia has also warned against moving defensive missiles to Turkey's border with Syria.[138]

After the meeting, the Russian ambassador to NATO said Russia was feeling comfortable without having co-operative relations with the alliance; he noted that at the time Russia and NATO had no positive agenda to pursue.[139] The NATO secretary general, Jens Stoltenberg, said: "NATO and Russia have profound and persistent disagreements. Today's meeting did not change that."[140][141]

The opening of the first site of the NATO missile defence system in Deveselu, Romania, in May 2016 led Russia to reiterate its position that the U.S.-built system undermined Russia's security, posed "direct threat to global and regional security", was in violation of the INF, and that measures were "being taken to ensure the necessary level of security for Russia".[142]

A June 2016 Levada poll found that 68% of Russians think that deploying NATO troops in the former Eastern bloc countries bordering Russia is a threat to Russia.[143]

The NATO summit held in Warsaw in July 2016 approved the plan to move four battalions totaling 3,000 to 4,000 troops on a rotating basis by early 2017 into the Baltic states and eastern Poland and increase air and sea patrols to reassure allies who were once part of the Soviet bloc.[144] The adopted Communique explained that the decision was meant "to unambiguously demonstrate, as part of our overall posture, Allies' solidarity, determination, and ability to act by triggering an immediate Allied response to any aggression."[145] The summit reaffirmed NATO's previously taken decision to "suspend all practical civilian and military cooperation between NATO and Russia, while remaining open to political dialogue with Russia".[146]

Heads of State and Government "condemned Russia's ongoing and wide-ranging military build-up" in Crimea and expressed concern over "Russia's efforts and stated plans for further military build-up in the Black Sea region".[147] They also stated that Russia's "significant military presence and support for the regime in Syria", and its military build-up in the Eastern Mediterranean "posed further risks and challenges for the security of Allies and others".[148] NATO leaders agreed to step up support for Ukraine: in a meeting of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, the Allied leaders reviewed the security situation with President of Ukraine Petro Poroshenko, welcomed the government's plans for reform, and endorsed a Comprehensive Assistance Package for Ukraine aimed to "help make Ukraine's defence and security institutions more effective, efficient and accountable".[149]

At the meeting of the Russia–NATO Council at the level of permanent representatives that was held shortly after the Warsaw summit, Russia admonished NATO against intensifying its military activity in the Black Sea.[150] Russia also said it agreed to have its military aircraft pilots flying over the Baltic region turn on the cockpit transmitters, known as transponders, if NATO planes acted likewise.[151]

In July 2016, Russia's military announced that a regiment of long-range surface-to-air S-400 weapon system would be deployed in the city of Feodosia in Crimea in August that year, beefing up Russia's anti-access/area denial capabilities around the peninsula.[152]

2017[edit]

On 18 February 2017, the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Sergey Lavrov said he supported the resumption of military cooperation with the NATO alliance.[153] In late March 2017, the Council met in advance of a NATO Foreign Ministers conference in Brussels, Belgium.[154]

In July 2017, the NATO-Russia Council met in Brussels. Following the meeting, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said that Allies and Russia had had a "frank and constructive discussion" on Ukraine, Afghanistan, and transparency and risk reduction.[155] The two sides briefed each other on the upcoming Russia's/Belarus′ Zapad 2017 exercise, and NATO's Exercise Trident Javelin 2017, respectively.[156]

At the end of August 2017, NATO declared that NATO's four multinational battlegroups in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania and Poland were fully operational, a move that was implemented pursuant to the decision taken at the 2016 Warsaw summit.[157]

In 2017, UK Secretary of State for Defence Michael Fallon warned that Russia's Zapad 2017 exercise in Belarus and Russia's Kaliningrad Oblast was "designed to provoke us". Fallon falsely claimed that the number of Russian troops taking part in exercise could reach 100,000, although technically Russia could have increased the number of participating troops to 100,000 and beyond had it felt like doing so.[158]

2018[edit]

In February 2018, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg stated: "We don't see any threat [from Russia] against any NATO ally and therefore, I'm always careful speculating too much about hypothetical situations."[159] Stoltenberg welcomed the 2018 Russia–United States summit between Vladimir Putin and Donald Trump in Helsinki, Finland.[160] He said NATO is not trying to isolate Russia.[161]

In response to the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal on 4 March 2018, Stoltenberg announced on 27 March 2018 that NATO would be expelling seven Russian diplomats from the Russian mission to NATO in Brussels. In addition, 3 unfilled positions at the mission were denied accreditation from NATO. Russia blamed the US for the NATO response.[162]

2019–20[edit]

In April 2019, NATO Secretary General Stoltenberg warned a joint session of the U.S. Congress of the threat posed by "a more assertive" Russia to the alliances members, which included a massive military buildup, threats to sovereign states, the use of nerve agents and cyberattacks.[163][164]

On 23 August 2019, another extrajudicial assassination was performed by Russian intelligence on NATO territory. At around midday in the Kleiner Tiergarten park in Berlin, Germany, Zelimkhan Khangoshvili, an ethnic Chechen Georgian who was a former platoon commander for the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria during the Second Chechen War, and a Georgian military officer during the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, was walking down a wooded path on his way back from the mosque he attended when he was shot three times—once in the shoulder and twice in the head—by a Russian assassin on a bike with a suppressed Glock 26. The bicycle, a plastic bag with the murder weapon, and a wig the perpetrator was using were dumped into the Spree.[165] The suspect, identified as 56-year-old Russian national "Vadim Sokolov" by German police, was apprehended soon after the assassination.[166][167] The Russian government and Chechen leader Ramzan Kadyrov have both been linked to the killing.[168][169]

In September 2019, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov said that "NATO approaching our borders is a threat to Russia."[170] He was quoted as saying that if NATO accepts Georgian membership with the article on collective defense covering only Tbilisi-administered territory (i.e., excluding the Georgian territories of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, both of which are currently unrecognized breakaway republics supported by Russia), "we will not start a war, but such conduct will undermine our relations with NATO and with countries who are eager to enter the alliance."[171]

2021[edit]

On 13 April 2021, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg called on Russia to halt its buildup of forces near the border with Ukraine.[172][173] Russian Defense Minister Sergey Shoygu said that Russia has deployed troops to its western borders for "combat training exercises" in response to NATO "military activities that threaten Russia."[174] Defender-Europe 21, one of the largest NATO-led military exercises in Europe in decades, began in mid-March 2021 and lasted until June 2021. It included "nearly simultaneous operations across more than 30 training areas" in Estonia, Bulgaria, Romania and other countries.[174][175]

On 6 October 2021, NATO decided to expel eight Russian diplomats, described as "undeclared intelligence officers", and halve the size of Russia's mission to the alliance in response to suspected malign activities.

The eight diplomats were expected to leave Brussels, where the alliance is headquartered, by the end of October and their positions scrapped. Two other positions that are currently vacant were also abolished. This reduced the size of the Russian mission to NATO in the Belgian capital to 10. [176] On 18 October 2021, Russia suspended its mission to NATO and ordered the closure of NATO's office in Moscow in retaliation for NATO's expulsion of Russian diplomats.[11]

In November 2021, Russian President Vladimir Putin stated that an expansion of NATO's presence in Ukraine, especially the deployment of any long-range missiles capable of striking Russian cities or missile defence systems similar to those in Romania and Poland, would be a "red line" issue for Russia.[177][178][179] Putin asked U.S. President Joe Biden for legal guarantees that NATO wouldn't expand eastward or put "weapons systems that threaten us in close vicinity to Russian territory."[180] NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg replied that "It's only Ukraine and 30 NATO allies that decide when Ukraine is ready to join NATO. Russia has no veto, Russia has no say, and Russia has no right to establish a sphere of influence to try to control their neighbors."[181][182]

The prelude to the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine occurred with Russia demanding that NATO end all military activity in Eastern Europe and never admit Ukraine as a member, and also stated they wanted a legal guarantee to end further eastward expansion and a Russian veto on NATO membership of Ukraine, in spite of its sovereignty.[183] A senior Biden administration official later stated that the U.S. is "prepared to discuss Russia's proposals" with its NATO allies, but also stated that "there are some things in those documents that the Russians know will be unacceptable."[184]

Breakdown of relations, military build-up and increased tensions (2022–present)[edit]

2022[edit]

On 12 January 2022, the NATO-Russia Council met at NATO's HQ in Brussels to discuss Russia's recent military build-up near its border with Ukraine and Russia's demands for security guarantees in Europe. The respective delegations were led by U.S. Deputy Secretary of State, Wendy Sherman and NATO Secretary General, Jens Stoltenberg and Russian Deputy Foreign Minister, Alexander Grushko and Russian Deputy Defence Minister, Colonel General Alexander Fomin.[185][186]

Despite Russia's announcement on 16 February 2022, that military training in Moscow-annexed Crimea had stopped and Russia announced soldiers returning to their posts, NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg said it appeared that Russia was continuing its military build-up.[187]

On 24 February 2022, in the middle of an ongoing meeting of the United Nations Security Council which was summoned to discuss the ongoing crisis and was presided over by Russia at the time, Putin ordered the Russian army to launch a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, causing the largest conventional military aggression on a European state since World War II, and further deteriorating relations between NATO and Russia. NATO Response Force was activated and put on high alert, with NATO deploying a number of troops in Poland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Hungary and Bulgaria.[188] On 26 February 2022, Russia issued threats to Finland and Sweden in response to their aspiration to become NATO members.[189] On 16 May 2022, a day after Sweden and Finland applied for membership in NATO, during a summit of the CSTO, which is the NATO's counterpart, Vladimir Putin said:

Russia has no problems with these states [Sweden and Finland], and therefore in this sense the expansion [of NATO] at the expense of these countries does not create a direct threat [...] but the expansion of military infrastructure in this region will certainly cause our response.

— Vladimir Putin[190]

The 2022 NATO Madrid summit declared Russia "a direct threat" to Euro–Atlantic security and approved an increase in the NATO Response Force to 300,000 troops, while the Founding Act had been thereafter considered by NATO member states as definitively abrogated in its entirety by Russia.[191][13] Meanwhile, since the beginning of the war, Russian officials and propagandists have increasingly said that they are "at war" with the whole of NATO as well as the West, a statement the organization and its member states (including the U.S.) has repeatedly denied.[14]

Multiple scholars and journalists speculated that the invasion of Ukraine likely marked the beginning of a Second Cold War between NATO and Russia.[192][193] According to ISW, Russia decided to start the war because it believed NATO is weak, not because it felt any threat from NATO presence.[194]

2023[edit]

In December 2023 Putin declared creation of Leningrad Military District which he said was in response to Finland membership in NATO "causing problems". He also reiterated that Russia has no interest in attacking NATO countries.[194]

2024[edit]

This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (January 2024) |

Ideology and propaganda[edit]

Integration plans (1991–2004)[edit]

The idea of Russia becoming a NATO member has at different times been floated by both Western and Russian leaders, as well as some experts.[195] In February 1990, while negotiating German reunification at the end of the Cold War with U.S. Secretary of State James Baker, General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Mikhail Gorbachev said that "You say that NATO is not directed against us, that it is simply a security structure that is adapting to new realities ... therefore, we propose to join NATO." However, Baker dismissed the possibility as a "dream".[196] In 1991, as the Soviet Union was dissolved, Russian president Boris Yeltsin sent a letter to NATO, suggesting that Russia's long-term aim was to join NATO.[197]

During a series of interviews with filmmaker Oliver Stone, President Vladimir Putin told him that he floated the possibility of Russia joining NATO to President Bill Clinton when he visited Moscow in 2000.[198][199] Putin said in a BBC interview with David Frost just before Putin was inaugurated as President of Russia for the first time in 2000 that it was hard for him to visualize NATO as an enemy. "Russia is part of the European culture. And I cannot imagine my own country in isolation from Europe and what we often call the civilized world."[200] Former NATO Secretary General George Robertson was asked by Putin for Russia to join NATO.[201] According to Anders Fogh Rasmussen, the former Danish Prime Minister who served as NATO Secretary General from 2009 to 2014, in the early days of Putin's presidency around 2000–2001, Putin made many statements that suggested he was favorable to the idea of Russia joining NATO.[199]

Disillusionment (2004–2013)[edit]

On 7 October 2006, Anna Politkovskaya, a Russian journalist[202] who reported on political events in Russia; in particular, the Second Chechen War (1999–2005),[203] was murdered in the elevator of her block of flats, an assassination that attracted international attention.[204][205][206] In response to a March 2009 suggestion by Polish foreign minister Radosław Sikorski that Russia join NATO, the Russian envoy to NATO, Dmitry Rogozin, stated that while Russia had not ruled it out as a future possibility, it instead preferred to keep practical limited cooperation with NATO. He emphasized that "Great powers don't join coalitions, they create coalitions. Russia considers itself a great power." However, he stated that Russia wanted to be NATO's "partner", provided that Georgia (with which Russia had a war the previous year) and Ukraine did not join the alliance.[70] In November 2009, Sergei Magnitsky, a Ukrainian-born Russian tax advisor responsible for exposing corruption and misconduct by Russian government officials while representing client Hermitage Capital Management, died.[207] His arrest in 2008 and subsequent death after eleven months in police custody generated international attention and triggered both official and unofficial inquiries into allegations of fraud, theft and human rights violations in Russia.[208][209][210] His posthumous trial was the first in the Russian Federation. In spite of that, the suggestion of Russia joining NATO was repeated in an open letter co-written in early 2010 by some German defense experts. They posited that Russia was needed in the wake of an emerging multi-polar world in order for NATO to counterbalance emerging Asian powers.[211] Meanwhile, the United States responded with adoption of the Magnitsky Act in 2012.

Increased hostility and further confrontation (2014–present)[edit]

Countries on Russia's "Unfriendly Countries List". Countries and territories on the list imposed sanctions against Russia following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[212]

Putin, however, later abandoned the ideas of the European integration and the Western democracy, turning instead to "Eurasia Movement"[213] and "Putinism" advertised as alternatives competing with the Western and European ideals espoused by many NATO countries.[214] Eurasia Movement is a Duginism-based neo-Eurasianist political movement, according to which Russia does not belong in the "European" or "Asian" categories but instead to the geopolitical concept of Eurasia dominated by the "Russian world/peace" (Russian: Русский мир), forming an ostensibly standalone Russian civilization which lost respect for the values and moral authority of the West, creating a "values gap" between Russia and the West.[215] Putin has promoted his brand of conservative Russian values, and has emphasized the importance of religion.[216] Gay rights have divided Russia and many NATO countries, as the United States and some European countries have used their soft power to promote the protection of gay rights in Eastern Europe.[217] Russia, on the other hand, has hindered the freedom of homosexuality and earned support from those opposed to gay marriage.[217][218] Putinism in turn combines state capitalism with authoritarian nationalism.[214]

Russia has started to fund international broadcasters such as RT, Rossiya Segodnya (including Sputnik), and TASS.[219] as well as several domestic media networks.[220][221] Russian media has been particularly critical of the United States.[222][223] In 2014, Russia cut off Voice of America radio transmissions after Voice of America criticized Russia's actions in Ukraine.[224] Russia's freedom of the press has received low scores in the Press Freedom Index of Reporters Without Borders, and Russia limits foreign ownership stakes of media organizations to no greater than 20%.[225] In January 2015, the UK, Denmark, Lithuania and Estonia called on the European Union to jointly confront Russian propaganda by setting up a "permanent platform" to work with NATO in strategic communications and boost local Russian-language media.[226] On 19 January 2015, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini said the EU planned to establish a Russia-language mass media body with a target Russian-speaking audience in Eastern Partnership countries: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, as well as in the European Union countries.[227] In March 2016, Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov admitted that Russia was at "information war" primarily with "Anglo-Saxon mass media".

On 27 February 2015, prominent leader of Russian democratic opposition Boris Nemtsov was murdered by receiving several shots from behind while crossing the Bolshoy Moskvoretsky Bridge in Moscow, close to the Kremlin walls and Red Square.[a][228] less than two days before he was due to take part in a peace rally against Russian involvement in the war in Ukraine and the financial crisis in Russia.[229][230] Less than three weeks before his murder, on 10 February, Nemtsov wrote on Russia's Sobesednik news website that his 87-year-old mother was afraid Putin would kill him. He added that his mother was also afraid for former oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky and anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny.[231][232][233] Russian journalist Ksenia Sobchak said that Nemtsov had been preparing a report proving the presence of Russian military in eastern Ukraine despite official denials.[234] The night after Nemtsov's murder, his papers, writings and computer hard drives were confiscated in a police search of his apartment on Malaya Ordynka street.[235] BBC News quoted him saying: "If you support stopping Russia's war with Ukraine, if you support stopping Putin's aggression, come to the Spring March in Maryino on 1 March."[232] Russian security services are believed to bear responsibility for the crime.[236] According to Bellingcat analysis Nemtsov was followed prior to the assassination by the same FSB team that would subsequently follow Vladimir Kara-Murza, Dmitry Bykov and Alexei Navalny before their suspected poisonings.[237] Vladimir Milov, a former deputy minister of energy and fellow opposition figure, said: "There is ever less doubt that the state is behind the murder of Boris Nemtsov" and stated that the objective had been "to sow fear."[238] Opposition activist Maksim Kats held Putin responsible: "If he ordered it, then he's guilty as the orderer. And even if he didn't, then [he is responsible] as the inciter of hatred, hysteria, and anger among the people."[239]

Anders Fogh Rasmussen said in 2019 that "Once Russia can show it is upholding democracy and human rights, NATO can seriously consider its membership."[199] In a 2019 interview with Time Magazine, Sergey Karaganov a close advisor to Putin, claimed that not inviting Russia to join NATO was "one of the worst mistakes in political history," "It automatically put Russia and the West on a collision course, eventually sacrificing Ukraine".[240] Kimberly Marten argued in 2020 that NATO's enlargement made it weaker, not stronger as Moscow feared. The bad relations that emerged after 2009 were mostly caused by Russian reaction to its declining influence in world affairs. Thirdly, Russia's strong negative reaction was manipulated and magnified by both nationalists and by Putin, as ammunition in their domestic political wars.[241][242] Current Russian leaderships' views of world politics "are deeply rooted in realist approaches to international relations" and they perceive "a major external military risk in NATO’s bringing the military infrastructure of its member countries near the borders of the Russian Federation; likewise, with further [formal] expansion of the Alliance."[243] This provides a threat-based legitimacy that allows them to consolidate their domestic position, implement harsh anti-democratic measures, and justify a military build-up and aggressive actions abroad.[243] On November 4, 2021, George Robertson, a former UK Labour defence secretary who led NATO between 1999 and 2003, told The Guardian that Putin made it clear at their first meeting that he wanted Russia to be part of western Europe. "Putin said: ‘When are you going to invite us to join Nato?’...They wanted to be part of that secure, stable prosperous west that Russia was out of at the time," he said.[200][201]

In 2022, Russia withdrew from the European Convention on Human Rights and was expelled from the Council of Europe altogether.

Trade and economy[edit]

Russia periodically blocked navigation via the Strait of Baltiysk in the 1990s. Since 2006 it has imposed a continuous blockade (both for Poland and the Russian Kaliningrad Oblast), despite entering in 2009 an international agreement concerning this matter.[244] As a result, Poland started to consider digging another canal across the Vistula Spit in order to circumvent this restriction,[245] and ultimately built the Vistula Spit canal in 2019–2022.

In 1998, Russia joined the G8, a forum of eight large developed countries, six of which are members of NATO, until being expelled in 2014.

The Russian economy is heavily dependent on the export of natural resources such as oil and natural gas, and Russia has used these resources to its advantage. Russia and the western countries signed in 1991 the Energy Charter Treaty establishing a multilateral framework for cross-border cooperation in the energy industry, principally the fossil fuel industry; Russia, however, postponed its ratification, linking it to the adoption of the Energy Charter Treaty Transit Protocol. Starting in the mid-2000s, Russia and Ukraine had several disputes in which Russia threatened to cut off the supply of gas. As a great deal of Russia's gas is exported to Europe through the pipelines crossing Ukraine, those disputes affected several NATO countries. While Russia claimed the disputes had arisen from Ukraine's failure to pay its bills, Russia may also have been motivated by a desire to punish the pro-Western government that came to power after the Orange Revolution.[246] In December 2006, Russia indicated that the ratification of the Energy Charter Treaty was unlikely due to the provisions requiring third-party access to Russia's pipelines.[247] On 20 August 2009, Russia officially informed the depository of the Energy Charter Treaty (the Government of Portugal) that it did not intend to become a contracting party to the treaty.[248] In 2012, Russia joined the World Trade Organization, an organization of governments committed to reducing tariffs and other trade barriers. These increased economic ties gave Russia access to new markets and capital, as well as political clout in the West and other countries. Russian gas exports came to be viewed as a weapon against NATO countries,[249] and the US and other Western countries have worked to lessen the dependency of Europe on Russia and its resources.[250]

While Russia's new role in the global economy presented Russia with several opportunities, it also made the Russian Federation more vulnerable to external economic trends and pressures.[251] Like many other countries, Russia's economy suffered during the Great Recession. Following the Crimean Crisis, several countries (including most of NATO) imposed sanctions on Russia, hurting the Russian economy by cutting off access to capital. As a further consequence, Russia has also been expelled from the G8.[252] At the same time, the global price of oil declined.[253] The combination of international sanctions and the falling crude price in 2014 and thereafter resulted in the 2014–16 Russian financial crisis.[253] Following the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, NATO members imposed further sanctions against Russia. Russia retaliated by placed member states of NATO (except Turkey) on a list of "unfriendly countries" along with other Western states.

Russia's foreign relations with NATO member states[edit]

See also[edit]

- Foreign relations of Russia

- Foreign relations of NATO

- Enlargement of NATO

- NATO open door policy

- Armenia–NATO relations

- Belarus–NATO relations

- Georgia–NATO relations

- Moldova–NATO relations

- Ukraine–NATO relations

- Finland–NATO relations

- Sweden–NATO relations

- Russia–Ukraine relations

- Russia–United States relations

- Russian invasion of Ukraine

- Russia–European Union relations

- Ukraine–Commonwealth of Independent States relations

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "The NATO Russian Founding Act | Arms Control Association". www.armscontrol.org. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Benson, Brett V. (2012). Constructing International Security: Alliances, Deterrence, and Moral Hazard. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 67. ISBN 978-1107027244.

- ^ "Russia says deployment of EU mission in Armenia to 'exacerbate existing contradictions'".

- ^ a b RAND, Russia's Hostile Measures: Combating Russian Gray Zone Aggression Against NATO in the Contact, Blunt, and Surge Layers of Competition (2020) online

- ^ "Twenty Years of Russian "Peacekeeping" in Moldova". Jamestown. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "President of Russia". 2 September 2008. Archived from the original on 2 September 2008. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew; Erlanger, Steven (27 February 2014). "Gunmen Seize Government Buildings in Crimea". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ Ellyatt, Holly (24 February 2022). "Russian forces invade Ukraine". CNBC. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Russia joins war in Syria: Five key points". BBC News. 1 October 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "Russia blocks trains carrying Kazakh coal to Ukraine | Article". 5 November 2021.

- ^ a b "Russia suspends its mission at NATO, shuts alliance's office". AP. 18 October 2021. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ Chernova, Anna; Fox, Kara. "Russia suspending mission to NATO in response to staff expulsions". CNN. Retrieved 19 October 2021.

- ^ a b "Madrid Summit ends with far-reaching decisions to transform NATO". NATO. 30 June 2022.

- ^ a b Vavra, Shannon (21 September 2022). "'The Time Has Come': Top Putin Official Admits Ugly Truth About War". The Daily Beast. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ Tisdall, Simon (5 March 2023). "Nato faces an all-out fight with Putin. It must stop pulling its punches". The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Retrieved 26 June 2023.

- ^ "Old adversaries become new partners". NATO.

- ^ Sarotte, Mary Elise (2014). "A Broken Promise? What the West Really Told Moscow About NATO Expansion". Foreign Affairs. 93 (5): 90–97. ISSN 0015-7120. JSTOR 24483307.

- ^ Iulian, Raluca Iulia (23 August 2017). "A Quarter Century of Nato-Russia Relations". Cbu International Conference Proceedings. 5: 633–638. doi:10.12955/cbup.v5.998. ISSN 1805-9961.

- ^ "First NATO Secretary General in Russia". NATO.

- ^ Zollmann, Florian (30 December 2023). "A war foretold: How Western mainstream news media omitted NATO eastward expansion as a contributing factor to Russia's 2022 invasion of the Ukraine". Media, War & Conflict. doi:10.1177/17506352231216908. ISSN 1750-6352.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is available under the CC BY 4.0 license.

- ^ Korshunov, Maxim. "Mikhail Gorbachev: I am against all walls". rbth.com. Retrieved 12 May 2024.

- ^ "NATO's Relations With Russia". NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 6 April 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "NATO Strategic Concept for the Defence and Security of the Members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization" (PDF). NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 20 November 2010. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "The NATO-Russia Archive - Formal NATO-Russia Relations". Berlin Information-Center For Translantic Security (BITS), Germany. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ "NATO PfP Signatures by Date". NATO Public Diplomacy Division, Belgium. 10 January 2012. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: Scholarly debates, policy implications, and roads not taken. Evaluating NATO Enlargement: From Cold War Victory to the Russia-Ukraine War: Springer International Publishing; 2023. p. 1-42 doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7_1.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: From cold war victory to the Russia-Ukraine war: Springer International Publishing; 2023. 1-645 p doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7.

- ^ Ronald D. Azmus, Opening NATO's Door (2002) p. 210.

- ^ Strobe Talbott, The Russia Hand: A Memoir of Presidential Diplomacy (2002) p. 246.

- ^ Fergus Carr and Paul Flenley, "NATO and the Russian Federation in the new Europe: the Founding Act on Mutual Relations." Journal of Communist Studies and Transition Politics 15.2 (1999): 88–110.

- ^ "5/15/97 Fact Sheet: NATO-Russia Founding Act". 1997-2001.state.gov. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ a b "NATO Publications". www.nato.int. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ "Nato-Russia Council - Documents & Glossaries". www.nato.int. Retrieved 28 May 2022.

- ^ The NATO-Russia Joint Editorial Working Group (8 June 2021). "NATO-Russia Glossary of Contemporary Political and Military Terms" (PDF).

- ^ "Yeltsin: Russia will not use force against Nato". The Guardian. 25 March 1999.

- ^ "Yeltsin warns of possible world war over Kosovo". CNN. 9 April 1999.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: From cold war victory to the Russia-Ukraine war: Springer International Publishing; 2023. 1-645 p doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7. p.165.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: From cold war victory to the Russia-Ukraine war: Springer International Publishing; 2023. 1-645 p doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7.

- ^ "Russia Condemns NATO's Airstrikes". Associated Press. 8 June 1999.

- ^ Jackson, Mike (2007). Soldier. Transworld Publishers. pp. 216–254. ISBN 9780593059074.

- ^ "Confrontation over Pristina airport". BBC News. 9 March 2000.

- ^ Peck, Tom (15 November 2010). "Singer James Blunt 'prevented World War 3'". Belfast Telegraph.

- ^ "Ex-Nato head says Putin wanted to join alliance early on in his rule". The Guardian. 4 November 2021. Retrieved 22 February 2024.

- ^ Hall, Todd (September 2012). "Sympathetic States: Explaining the Russian and Chinese Responses September 11". Political Science Quarterly. 127 (3): 369–400. doi:10.1002/j.1538-165X.2012.tb00731.x.

- ^ "NATO–Russia Council Statement 28 May 2002" (PDF). NATO. 28 May 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 February 2022. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Nato-Russia Council - About". www.nato.int. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ NATO. "NATO - Official text: Founding Act on Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security between NATO and the Russian Federation signed in Paris, France, 27-May.-1997". NATO. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Cook, Lorne (25 May 2017). "NATO: The World's Largest Military Alliance Explained". www.MilitaryTimes.com. The Associated Press, US. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ "Structure of the NATO-Russia Council" (PDF). Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ "Nato Blog | Dating Council". www.nato-russia-council.info. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Nat-o Blog | Dating Council". www.nato-russia-council.info.

- ^ "Nato Blog | Dating Council". www.nato-russia-council.info. Archived from the original on 8 February 2009.

- ^ "Allies and Russia attend U.S. Nuclear Weapons Accident Exercise". Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2008.

- ^ Goldgeier J, Shifrinson JRI. Evaluating NATO enlargement: From cold war victory to the Russia-Ukraine war: Springer International Publishing; 2023. 1-645 p doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-23364-7.

- ^ Guinness World Records: First murder by radiation:

On 23 November 2006, Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Litvinenko, a retired member of the Russian security services (FSB), died from radiation poisoning in London, UK, becoming the first known victim of lethal Polonium 210-induced acute radiation syndrome. - ^ "CPS names second suspect in Alexander Litvinenko poisoning". The Telegraph. 29 February 2012. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022.

- ^ Chapter 2. Rights and Freedoms of Man And Citizen | The Constitution of the Russian Federation. Constitution.ru. Retrieved on 12 August 2013.

- ^ "Russia warns of resorting to 'force' over Kosovo". France 24. 22 February 2008.

- ^ In quotes: Kosovo reaction, BBC News Online, 17 February 2008.

- ^ "Putin calls Kosovo independence 'terrible precedent'". The Sydney Morning Herald. 23 February 2008.

- ^ "NATO's relations with Russia".

- ^ "Ukraine: NATO's original sin". Politico. 23 November 2021.

- ^ Menon, Rajan (10 February 2022). "The Strategic Blunder That Led to Today's Conflict in Ukraine". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Bush backs Ukraine on Nato bid, BBC News (1 April 2008)

- ^ Ukraine Says 'No' to NATO, Pew Research Center (29 March 2010)

- ^ "Medvedev warns on Nato expansion". BBC News. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ "Bush stirs controversy over NATO membership". CNN. 1 April 2008.

- ^ "NATO Press Release (2008)108 – 27 Aug 2008". Nato.int. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "NATO Press Release (2008)107 – 26 Aug 2008". Nato.int. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ a b Pop, Valentina (1 April 2009). "Russia does not rule out future NATO membership". EUobserver. Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ "Nato-Russia relations plummet amid spying, Georgia rows". Retrieved 1 May 2009.

- ^ "Военные считают ПРО в Европе прямой угрозой России – Мир – Правда.Ру". Pravda.ru. 22 August 2007. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ a b "Q&A: US missile defence". BBC News. 20 September 2009. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ^ NATO chief asks for Russian help in Afghanistan Reuters Retrieved on 9 March 2010

- ^ Angela Stent, The Limits of Partnership: U.S.-Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century (2014) pp 230–232.

- ^ "Russia's 2008 war with Georgia prevented NATO growth – Medvedev | Russia | RIA Novosti". En.ria.ru. 21 November 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- ^ "Russian and Nato jets to hold first ever joint exercise". Telegraph. 1 June 2011. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ "Nato rejects Russian claims of Libya mission creep". The Guardian. 15 April 2011.

- ^ "West in "medieval crusade" on Gaddafi: Putin Archived 23 March 2011 at the Wayback Machine." The Times (Reuters). 21 March 2011.

- ^ Kramer, Andrew E. (21 April 2012). "Russians Protest Plan for NATO Site in Ulyanovsk". The New York Times.

- ^ "NATO warns Russia to cease and desist in Ukraine". Euronews.com. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 2 March 2014.

- ^ "Ukraine Crisis: NATO Suspends Russia Co-operation". BBC News, UK. 2 April 2014. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ^ a b "Statement by NATO Foreign Ministers - 1 April 2014". NATO.

- ^ "Address by President of the Russian Federation". President of Russia.

- ^ "Why the Kosovo "precedent" does not justify Russia's annexation of Crimea". Washington Post.

- ^ Lars Molteberg Glomnes (25 March 2014). "Stoltenberg med hard Russland-kritikk" [Stoltenberg was met with fierce criticism from Russia]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 29 March 2014.

- ^ "Stoltenberg: – Russlands annektering er en brutal påminnelse om Natos viktighet" [Stoltenberg: – Russia's annexation is a brutal reminder of the importance of NATO]. Aftenposten (in Norwegian). 28 March 2014. Archived from the original on 29 March 2014.

- ^ Tron Strand, Anders Haga; Kjersti Kvile, Lars Kvamme (28 March 2014). "Stoltenberg frykter russiske raketter" [Stoltenberg fears of Russian missiles]. Bergens Tidende (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 31 March 2014.

- ^ "NATO-Russia Relations: The Background" (PDF). NATO. March 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2021.

- ^ Joint Statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, 4 September 2014.

- ^ Joint statement of the NATO-Ukraine Commission, 2 December 2014.

- ^ MacAskill, Ewen (9 November 2014). "Close military encounters between Russia and the west 'at cold war levels'". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ "Russia Baltic military actions 'unprecedented' - Poland". UK: BBC News. 28 December 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ "Four RAF Typhoon jets head for Lithuania deployment". UK: BBC News. 28 April 2014. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ "U.S. asks Vietnam to stop helping Russian bomber flights". Reuters. 11 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- ^ "Russian Strategic Bombers To Continue Patrolling Missions". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2 March 2015. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- ^ Schwartz, Paul N. (16 October 2014). "Russian INF Treaty Violations: Assessment and Response". Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ a b Gordon, Michael R. (28 July 2014). "U.S. Says Russia Tested Cruise Missile, Violating Treaty". The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ "US and Russia in danger of returning to era of nuclear rivalry". The Guardian. UK. 4 January 2015. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. (5 June 2015). "U.S. Says Russia Failed to Correct Violation of Landmark 1987 Arms Control Deal". The New York Times. US. Retrieved 7 June 2015.

- ^ Bodner, Matthew (3 October 2014). "Russia Overtakes U.S. in Nuclear Warhead Deployment". The Moscow Times. Moscow. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- ^ The Trillion Dollar Nuclear Triad Archived 23 January 2016 at the Wayback Machine James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies: Monterey, CA. January 2014.

- ^ Broad, William J.; Sanger, David E. (21 September 2014). "U.S. Ramping Up Major Renewal in Nuclear Arms". The New York Times. USA. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ^ "Russia's New Military Doctrine Hypes NATO Threat". 30 December 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ Putin signs new military doctrine naming NATO as Russia's top military threat National Post, December 26, 2014.

- ^ Statement of Foreign Ministers on the Readiness Action Plan NATO, 02 Dec 2014.

- ^ "NATO condemns Russia, supports Ukraine, agrees to rapid-reaction force". New Europe. Retrieved 22 April 2016.

- ^ "Nato shows its sharp end in Polish war games". Financial Times. UK. 19 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "Nato testing new rapid reaction force for first time". UK: BBC News. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "NATO Head Says Russian Anti-Terror Cooperation Important". Bloomberg. 8 January 2015

- ^ "Insight - Russia's nuclear strategy raises concerns in NATO". Reuters. 4 February 2015. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ Croft, Adrian (6 February 2015). "Supplying weapons to Ukraine would escalate conflict: Fallon". Reuters. Retrieved 6 February 2015.

- ^ a b Press Association (19 February 2015). "Russia a threat to Baltic states after Ukraine conflict, warns Michael Fallon". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ А.Ю.Мазура (10 March 2015). "Заявление руководителя Делегации Российской Федерации на переговорах в Вене по вопросам военной безопасности и контроля над вооружениями". RF Foreign Ministry website.

- ^ Grove, Thomas (10 March 2015). "Russia says halts activity in European security treaty group". Reuters. UK. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- ^ Aksenov, Pavel (24 July 2015). "Why would Russia deploy bombers in Crimea?". London: BBC. Retrieved 3 December 2015.

- ^ "From Russia with Menace". The Times. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ Higgins, Andrew (1 April 2015). "Norway Reverts to Cold War Mode as Russian Air Patrols Spike". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ a b MacFarquhar, Neil, "As Vladimir Putin Talks More Missiles and Might, Cost Tells Another Story", New York Times, June 16, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-17.

- ^ Not a single Russia-NATO cooperation program works — Russian diplomat TASS, 16 June 2015.

- ^ "US announces new tank and artillery deployment in Europe". UK: BBC. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ "NATO shifts strategy in Europe to deal with Russia threat". UK: FT. 23 June 2015. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- ^ a b "Putin says Russia beefing up nuclear arsenal, NATO denounces 'saber-rattling'". Reuters. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ Комментарий Департамента информации и печати МИД России по итогам встречи министров обороны стран-членов НАТО the RF Foreign Ministry, 26 June 2015.

- ^ Steven Pifer, Fiona Hill. "Putin's Risky Game of Chicken", New York Times, June 15, 2015. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- ^ Steven Pifer. Putin's nuclear saber-rattling: What is he compensating for? 17 June 2015.

- ^ "Russian Program to Build World's Biggest Intercontinental Missile Delayed". The Moscow Times. 26 June 2015. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- ^ telegraph.co.uk: "US confirms it will place 250 tanks in eastern Europe to counter Russian threat", 23 Jun 2015

- ^ telegraph.co.uk: "Nato updates Cold War playbook as Putin vows to build nuclear stockpile", 25 Jun 2015